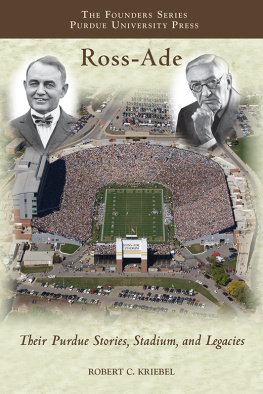

Ross-Ade

Ross-Ade

Their Purdue Stories, Stadium,

and Legacies

Robert C. Kriebel

Purdue University Press

Copyright 2009 by Purdue University. All rights reserved.

Front cover photo courtesy of Purdue University Sports Information Archives.

The typeface used on the front cover for the title and subtitle is CentaurMT. The typeface Centaur was designed by Bruce Rogers, Purdue University class of 1890.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kriebel, Robert C., 1932-

Ross-Ade : their Purdue stories, stadium, and legacies / by Robert C. Kriebel.

p. cm. -- (The founders series)

ISBN 978-1-55753-522-1

1. Ross, David, 1871-1943. 2. Ade, George, 1866-1944. 3. Purdue University--Benefactors--Biography. 4. Ross-Ade Stadium (West Lafayette, Ind.)--History. I. Title.

LD4672.65.R67.K75 2009

378.77295--dc22

[B]

2009006172

Contents

The author is indebted to the following persons for their helpful cooperation in the preparation of Ross-Ade: Their Purdue Stories, Stadium, and Legacies:

Byron L. Anderson, Purdue Alumni Association, West Lafayette

James F. Blakesley, West Lafayette, President, Purdue Class of 1950

Richard Dick Freeman, International Pacific, Corona del Mar, California, Purdue Distinguished Engineering Alumnus, 1973.

Amanda Grossman, Library Assistant, Purdue Archives and Special Collections

Kelly Hiller, Director of Creative Communication and Editor, The Purdue Alumnus.

Chris Horney, President, Sigma Chi Fraternity, Purdue University, West Lafayette

David Hovde, Associate Professor, Purdue University Libraries

Fern Martin, West Lafayette

Kathryn Matter, Purdue University Department of Bands

Joanne Mendes, Archives Assistant, Purdue Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries

Sammie L. Morris, Assistant Professor of Library Science and Head of Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries.

Cory Palm, Purdue University Sports Information Department.

Nicki (Reas) Meneley, Assistant Executive Director, Purdue Alumni Association.

Tom Schott, Assistant Athletic Director-Communications, Purdue University

C. Wesley Shook, President, The Area Plan Commission of Tippecanoe County, West Lafayette

James C. Shook, Senior Chairman of North Central Health Services Inc.s Board of Directors, West Lafayette

Bernie Sergesketter, Winnetka, Illinois, Sigma Chi Fraternity

Philip R. Steele, Sigma Chi Fraternity

The late Robert W. Topping (1925-2009), retired Senior Editor, Purdue University Publications

Paula Alexander Woods, retired from the staff of the Lafayette-West Lafayette Convention and Visitors Bureau

As the crow flies (they measure distance that-a-way in Indiana), the country towns of Brookston and Kentland lie thirty-six miles apart. Between them the crows out there flap over level fields of corn, oats, soybeans, wheat, and hay.

With Purdue University off to the south, Brookston and Kentland have formed a triangle for more than a century. As the crows fly, Purdue is fourteen miles from Brookston, thirty-seven miles southeast of Kentland

In the space of fifty-eight years, a remarkable thing took place in that triangle. Two boys from farms near Brookston and Kentland attended Purdue. One turned dreamer and became a writer. The other mastered drawing and invented machines. After graduations six years apart, both men earned fames and fortunes.

Distant strangers as Purdue alumni, they met at last in 1922, in a county judges office. That afternoon they got dust on their good leather shoes by hiking shallow hills and weeds on an old farm. They stood on a stretch of high ground and shared a vision that day, made a deal, shook hands, bought the farm, and on it started a football stadium still booming at Purdue.

The strangers were Dave Ross and George Ade. Because they met, the rest is history.

Robert C. Kriebel

Lafayette, Indiana

May 2009

T eenage John Ade sailed over to the United States from a brewery job in Lewes, England, in the summer of 1840. His family spent a week in New York City, then tried Cincinnati. John took up schoolwork and drove a team for a contractor. He married Adaline Bush when he was twenty-three and she was eighteen. Adalines mother was an Adair. Coincidentally, Englands Ades were kin to Scotlands Adairs. When opportunity knocked in 1852, the newlywed Ades moved to rural Morocco in Jasper County of northwestern Indiana.

John Ade farmed and managed a country store in Morocco. In 1853, He became Moroccos first postmaster, too, under Whig-Republican Millard Fillmores presidency. But when Franklin Pierce reached the White House, Democrat kingmakers fired Postmaster Ade for offensive partisanship. A Republican he was, by God, and a Republican he would stay.

In 1859, Indiana government snipped off part of Jasper County and Morocco and with those acres formed NewtonIndianas last county. The voters in Newton County elected their grocer friend John Ade to be Recorder. The Ades left Morocco for Kentland, four miles from the Illinois line. Kentland was where the new courthouse would go and where the Recorders office would be. The Ades little story-and-a-half frame house, the second one to go up in Kentland, faced the south side of the courthouse square. That house became the birthplace of George, the fifth of John and Adaline Ades six children, on February 9, 1866.

John quit storekeeping to hammer out a living as a blacksmith and finally to put on a suit and be cashier of the new Discount and Deposit Bank in Kentland.

George grew up in a happy enough home in the town of six hundred. He had two brothers and three sisters. He would call his mothers goodness unbounded, remembering her as being so rooted in unruffled common sense and entire lack of theatrical emotionalism that I sometimes marveled at the fact that, from no merit of my own, I was privileged to have such a remarkable mother. (Kelly, Ade, 21)

Sons and daughters alike in those days carried out their chores and attended some dinky village or township school. George, although dismissed by some as a hopeless work-dodger and day-dreamer, did at least show an early love for drama and literature. Writing, and doing so with a droll sense of humor, came to George naturally, early, and easily.

When I was a small boy, he still recalled when he was fifty-two, being on a farm the year round was a good deal like being in jail, except that the prisoners in jail were not required to work fourteen hours a day. The good old days were not so good, and the nights were worse. Describing the same general era and his boyhood job of lighting the household lamps, George wrote:

I had to climb a ladder and struggle with slow-burning brimstone matches to touch off the charred wick and eventually flood a few square feet with modified gloom. The old-fashioned coal-oil lamp threw out a weak yellow glare. After you had one lightedyou had to start another so you could tell where you had put the first one. (Kelly, Ade, 24)

As for the Indiana farmland spreading for miles around him, George would record:

The explorer could start from anywhere out on the prairie and move in any direction and find a slough, and in the center of it an open pond of dead water. Then a border of swaying cattails, tall rushes, reedy blades sharp as razors, out to the upland, spangled with the gorgeous blue and yellow flowers of the virgin plain. A million frogs sang together each evening and a billion mosquitoes came out to forage when the breeze died away. The old-fashioned flimsy mosquito netting would not keep out anything under the size of a barn swallow. (Kelly,