I TATTI STUDIES IN ITALIAN RENAISSANCE HISTORY

Published in collaboration with I Tatti

Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies Florence, Italy

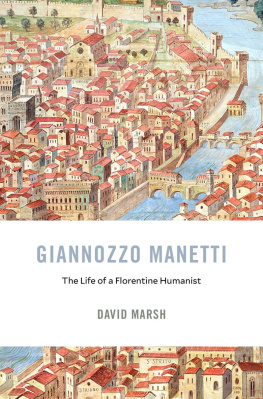

GIANNOZZO

MANETTI

The Life of a Florentine Humanist

DAVID MARSH

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2019

Copyright 2019 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Cover artwork: The Carta della Catena showing a panorama of Florence, 1490, Museo de Firenze, Florence, Italy. Courtesy of Bridgeman Images.

978-0-674-23835-0 (alk. paper)

978-0-674-24394-1 (EPUB)

978-0-674-24395-8 (MOBI)

978-0-674-24393-4 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Marsh, David, 1950 September 25 author.

Title: Giannozzo Manetti : the life of a Florentine humanist / David Marsh.

Other titles: I Tatti studies in Italian Renaissance history.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2019. | Series: I Tatti studies in Italian Renaissance history | Includes some text in Italian and Latin. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019006117

Subjects: LCSH: Manetti, Giannozzo, 13961459. | HumanistsItalyBiography.

Classification: LCC B785.M2444 M37 2019 | DDC 195 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006117

To Elizabeth

CONTENTS

- Manettis Early Years, Marriage, and First Public Offices

- Eloquence at Home and Abroad, 14371448

- Pistoia

- Venice and Other Cities, 14481453

- Life in Exile

- Scholarship in Rome

- Naples, 14551459: Late Works and Last Years

- Contemporary Reputation and Posthumous Fortune

G IANNOZZO M ANETTI (13961459) is one of the most remarkable figures of Florentine humanism in the fifteenth centurya successful merchant, a distinguished statesman, a prodigious scholar of history and philosophy, an accomplished Hebraist, and a prolific author of treatises and orations. Although we have little record of his business dealings, his participation in civic affairs is amply documented throughout his long career. As an official representative of the Florentine republic, he delivered funeral orations for prominent citizens like Leonardo Bruni and Giannozzo Pandolfini, and left a considerable corpus of public speeches written in both Latin and Italian. As a humanist scholar, he wrote important dialogues and treatises, including the celebrated treatise On the Dignity and Excellence of Man, which many consider a manifesto of the new worldview of Renaissance humanism. As a secular philosopher, he undertook the translation of Aristotles ethical treatises. As a precursor of Protestant theology, he offered a humanist alternative to the canonical versions of St. Jerome by translating into Latin both the Greek text of the New Testament and the Hebrew Psalms.

Our main sources for Manettis life are the writings of Vespasiano da Bisticci (14211498), who wrote a succinct Life and a longer Commentary in Italian; the latter work formed the basis of a Latin biography by Naldo Naldi (1439ca. 1513). We also have an Italian biography in Italian tercets that was probably composed by Vespasiano. Of these original sources, only the Life has been translated into English; and the interested reader will no doubt benefit from consulting Renaissance Princes, Popes and Prelates. The Vespasiano Memoirs: Lives of Illustrious Men of the XVth Century, translated by William George and Emily Waters (1926; reprinted in 1963 and 1997).

In the past thirty years, research on Giannozzo Manetti has grown rapidly, and the present study attempts to synthesize a wide range of recent findings. I owe a great debt to many specialists who have supplied valuable information and offered useful suggestions: Stefano Borsi, Luca Boschetto, Jeroen De Keyser, Anthony DElia, Annet Den Haan, Eugenia Fosalba Vela, Francesco Furlan, Timothy Kircher, Gary Rendsburg, Fabrizio Ricciardelli, David Rundle, Daniel Stein Kokin, Carlo Vecce, and Hartmut Wulfram. I owe special thanks to my friend and colleague Stefano Ugo Baldassarri, whose extensive researches and scholarly advice have been invaluable. In matters of classical Latin, I have benefited from the friendship and expertise of Robert A. Kaster, who kindly corrected an early draft. Stefano Ugo Baldassarri, Paul Botley, William J. Connell, and Brian Jeffrey Maxsonall recognized Manetti scholarsgenerously read the manuscript at various stages and offered many invaluable suggestions. My Rutgers colleague Marcie Anszperger helped with problems of word processing and formatting. I also wish to thank the personnel of the following libraries: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Biblioteca Marucelliana, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Biblioteca Riccardiana Firenze, Princeton University Library, and Rutgers University Library.

I thank my wife, Elizabeth, for her patience and love, and dedicate this book to her.

G IANNOZZO M ANETTI was born in Florence on 5 June 1396, the son of Bernardo Manetti, a money-lender and cloth merchant, and Piera Guidacci. During this period, the Manetti family owned or rented three adjacent properties on Via del Fondaccio (now Via Santo Spirito). According to the first catasto, the eighty-year-old head of the family Bernardo Manetti owned the first property, which was inherited by Giannozzo and his brother Filippo just four years later in 1431. In 1429, Giannozzo and Filippo bought the adjacent property, where Giannozzo lived until 1450. A third adjacent property was swapped with the first and definitively acquired by exchange in 1432, after which Filippo lived there.

The family also owned properties in the country, but they were scattered and not very lucrative. Giannozzo and Filippo followed their fathers example in preferring short-term lending to speculation in the market and in real estate. In 1431, about half their financial investments were in fixed deposits and obligations, and half in the riskier dry exchanges or unsecured loans, including a bad debt owed by Cosimo and Lorenzo de Medici! In 1433, three years after the death of their father Bernardo, the Manetti brothers Giannozzo and Filippo divided the family assets between their two households. Filippo inherited the third townhouse and various investments and credits; and Giannozzo received half the family fortune and the rest of the real estate, which he soon increased by acquiring properties in a rural district called Vacciano, southeast of Florence and west of present-day Ponte a Ema.

According to the catasto of 1433, the first in which the brothers Giannozzo and Filippo filed separately, Giannozzo had four medium-sized farms (the largest of which with a country house), a fifth small farm, a vineyard and cottage and eighteen other land parcels. Omitting his town and country houses, these estates were valued in all at 1860 florins. His government stock was worth 9621 florins in real values, and the remaining assets, made up of commercial and finance capital, totaled 3089 florins.