Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

THE SUBSTANCE OF FICTION

Premodern East Asia: New Horizons

PREMODERN EAST ASIA: NEW HORIZONS

This series is dedicated to books that focus on humanistic studies of East Asia before the mid-nineteenth century in fields including literature and cultural and social history, as well as studies of science and technology, the environment, visual cultures, performance, material culture, and gender. The series particularly welcomes works with field-changing and paradigm-shifting potential that adopt interdisciplinary and innovative approaches. Contributors to the series share the premise that creativity in method and rigor in research are preconditions for producing new knowledge that transcends modern disciplinary confines and the framework of the nation-state. In highlighting the complexity and dynamism of premodern societies, these books illuminate the relevance of East Asia to the contemporary world.

Becoming Guanyin: Artistic Devotion of Buddhist Women in Late Imperial China, Yuhang Li

Kinship Novels of Early Modern Korea: Between Genealogical Time and the Domestic Everyday, Ksenia Chizhova

The Substance of Fiction

Literary Objects in China, 15501775

Sophie Volpp

Columbia University PressNew York

This publication was made possible in part by an award from the James P. Geiss and Margaret Y. Hsu Foundation.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2022 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-55322-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Volpp, Sophie, 1963 author.

Title: The substance of fiction : literary objects in China, 15501775 / Sophie Volpp.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2022] | Series: Premodern East Asia: new horizons | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021038662 (print) | LCCN 2021038663 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231199643 (hardback ; acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780231199650 (trade paperback ; acid-free paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Chinese fictionMing dynasty, 13681644History and criticism. | Chinese fictionQing dynasty, 16441912History and criticism. | LCGFT: Literary criticism.

Classification: LCC PL2436 .V65 2022 (print) | LCC PL2436 (ebook) | DDC 895.13/4609dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021038662

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021038663

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

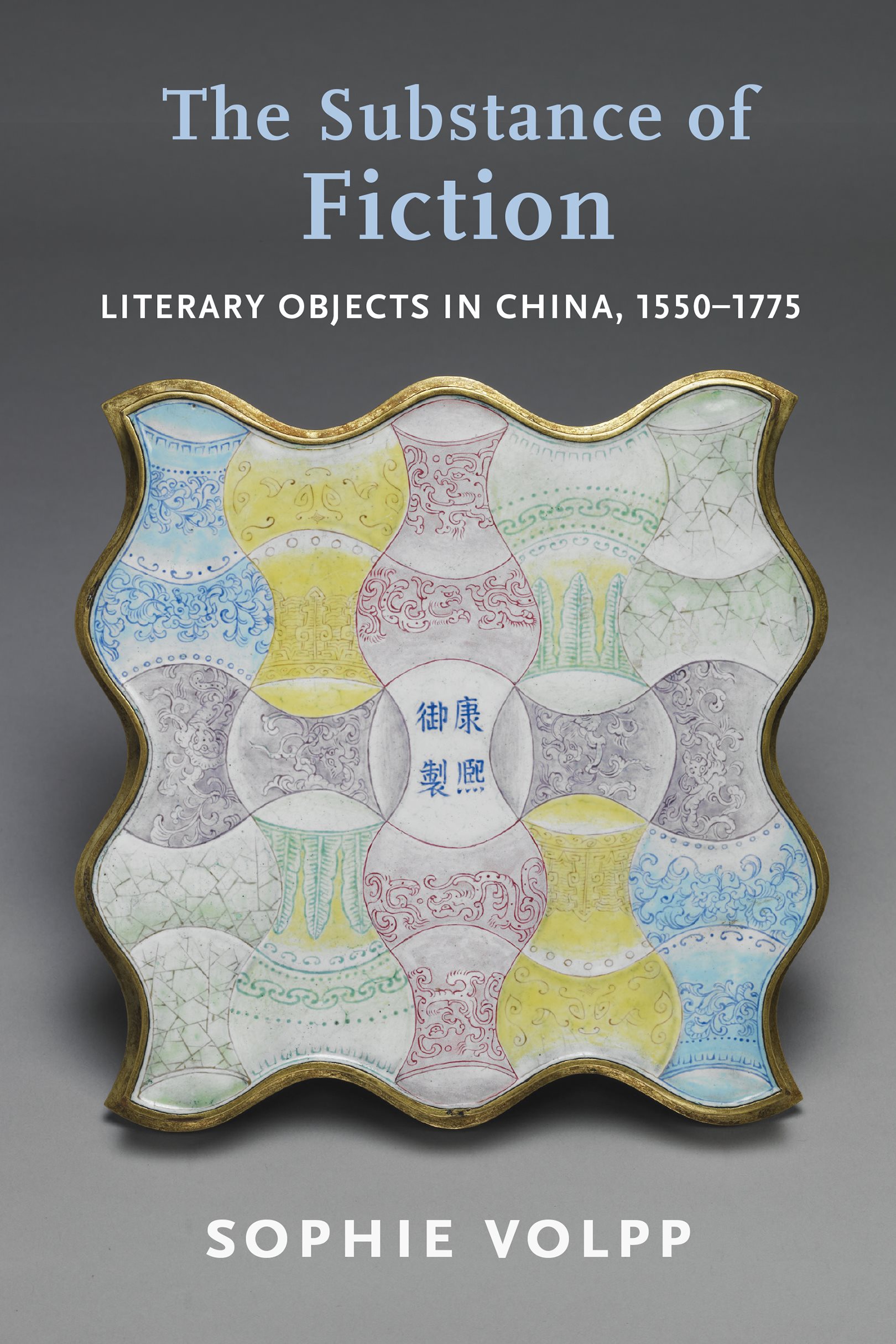

Cover image: Enameled tray of the Kangxi Reign period. National Palace Museum, Taipei.

For Daniel and Julia

Contents

This book grew out of many conversations with colleagues at Berkeley and beyond; I am grateful to all the scholars who took the time to share their knowledge with me. I thank Patricia Berger, Andrew Jones, Chana Kronfeld, Susan Maslan, Nick Paige, Karin Sanders, Bob Sharf, Mario Tel, and Paula Varsano for reading various chapters, and Robert Ashmore, Mark Blum, Mark Csikszentmihalyi, Ling Hon Lam, and Michael Nylan for answering my questions. Many thanks to Weihong Bao for her writing company and for convening our summer writing group, which extended far beyond a single summer. I thank Deniz Gktrk, Luba Golburt, and Anne Nesbet for suggestions both lighthearted and practical. My conversations with Dori Hale always led to new realizations. Liu Bo, Karl Britto, Judith Butler, Tim Hampton, Michael Lucey, Leslie Kurke, Nelly Oliensis, and Sandra Sjardono shared their wisdom in matters large and small.

I am grateful that several colleagues at institutions across the United States read the entire manuscript: Lynn Festa, Paize Keulemans, Dorothy Ko, Susan Naquin, Anna Shields, and Judith Zeitlin. I am particularly grateful to Shang Wei for his support of the research in . My deepest thanks go to Judith Zeitlin, who somehow was there at every significant stage in the writing of this book.

Many historians of art and architecture answered my questions about boxes, telescopes, mirrors, and tongjing hua painting, among them Nancy Berliner, Craig Clunas, Ellen Huang, Liu Chang, Wu Hung, and Ying Feier. Team-teaching a graduate seminar on The Story of the Stone with Patricia Berger was one of the most memorable experiences of my teaching life. Marco Musillo hosted me for several days in Florence, where we spent many hours in conversation about the wall painting that we playfully named The Lady with the Clock. At the Palace Museum in Beijing, Zhang Shuxian and Yuan Hongqi were extraordinarily generous. I am grateful to Wang Shiwei of the Palace Museum for permission to use his images in . Many thanks to my large family of aunts, uncles, and cousins for all the fun they provided on my research trips to Beijing, and especially to my aunt Yuan Jiu for her hospitality.

I worked on this book for many years, and in the final stages had occasion to remember every one of the research assistants who stood by my side. I would like to name those who pursued graduate study in Chinese literature: Naixi Feng, Hanyu Hou, Site Li, Tianyi Liu, Allyson Tang, and Jiaqian Zhu. Elysee Wilson-Egolf was my right arm for many years. Jane Yarnell gave me assistance at a critical moment. The questions and insights of many students enlivened my understanding of these texts over the years; in addition to those named above, I thank Keru Cai, Matteo Cavelier-Riccardi, Zijing Fan, Xiangjun Feng, Kris Kersey, William Ma, Hannibal Taubes, Michelle Wang, Xiaoyu Xia, and Shoufu Yin.

I am indebted to Dorothy Ko, the editor for the series in which this book appears, as well as to Christine Dunbar, Kathryn Jorge, Mary Bagg, and Christian Winting at Columbia University Press. The research for this book was supported by the American Philosophical Society, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Mellon Foundation, and the University of California, Berkeley.

So much of what brought me to this moment exists only in memory. I am thankful for those who remember with me: Leti, Kevin, and Serena Volpp; Matt Franklin; Tsing, Pat, and Elizabeth Yuan; Graciana Lapetina, Richard Perry, and Marjorie Volpp; Mike Bruhn, Nancy Kates, Kyu-hyun Kim, Karen Lam, Jenny Lin, Clemens Reichel, and Patrick Reichel.

In Daniel, I was blessed with a son of rare maturity, kindness, and consideration; and in Julia, with a daughter of extraordinary warmth, radiance, and courage. I love you both always and forever. This book is for you.

This book was inspired by the questions of my students, who pressed me to conceptualize more concretely the fictional worlds we jointly entered. Reading Feng Menglongs (15741645) story Jiang Xingge Re-encounters His Pearl Shirt (), they wanted to know why a vendor of pearls states that the silver she receives better have enough crackle in it (). In researching the answers to such questions (and finding that the pattern of the crackle indicates the percentage of silver in the alloy), I discovered the pleasure of unearthing lost historical resonance. And I began to wonder, thinking of another character in a Feng Menglong story, whether we would better understand the metaphorical relation between Du Shiniang and her jewel box if we had a more detailed portrait of the material features of seventeenth-century boxes.