MEDIEVAL THINGS

INTERVENTIONS: NEW STUDIES IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE

Ethan Knapp, Series Editor

Copyright 2020 by The Ohio State University.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bildhauer, Bettina, author.

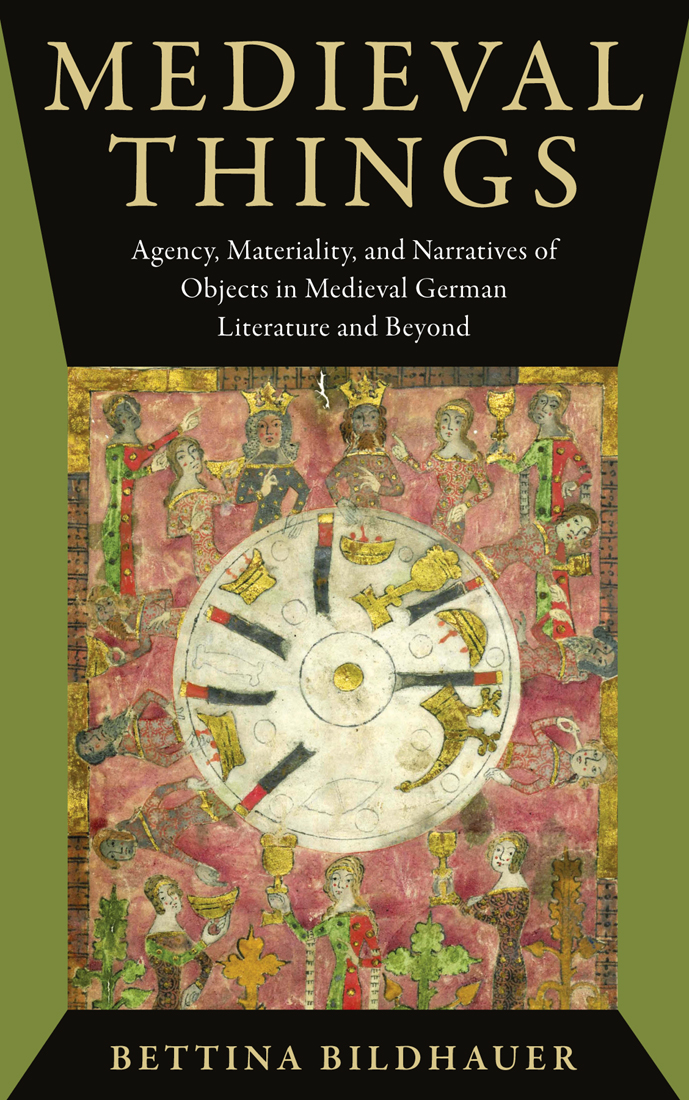

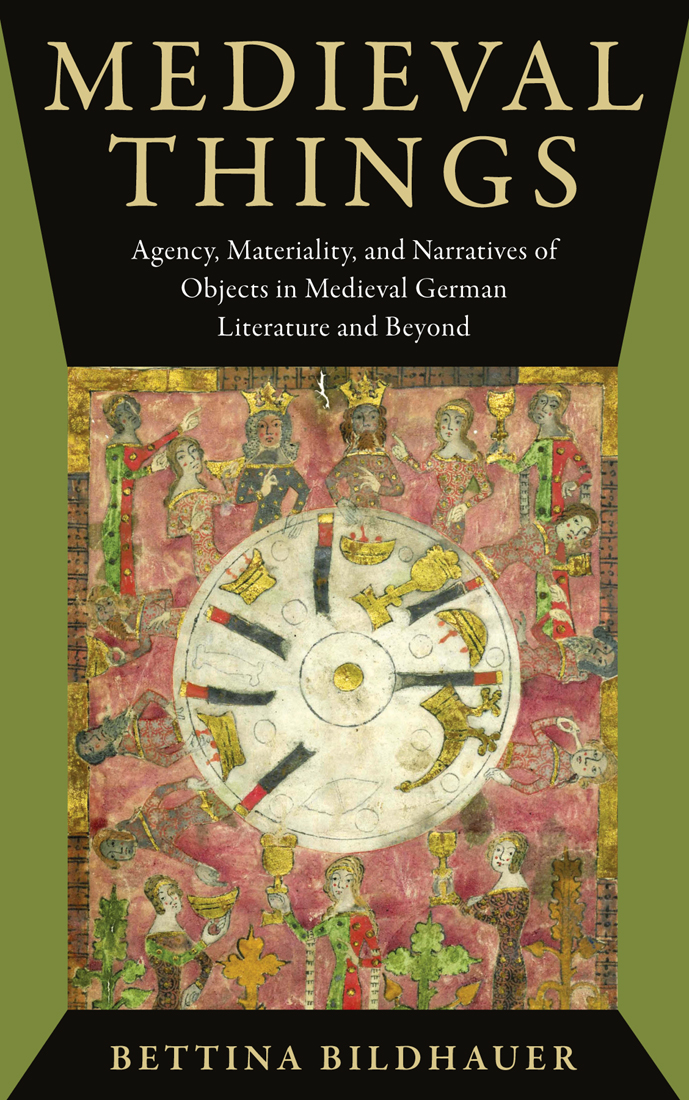

Title: Medieval things : agency, materiality, and narratives of objects in medieval German literature and beyond / Bettina Bildhauer.

Other titles: Interventions: new studies in medieval culture.

Description: Columbus : The Ohio State University Press, [ 2020 ] | Series: Interventions: new studies in medieval culture | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: Medieval Things brings together a theoretically informed and politically engaged new materialist approach to famous and forgotten German narratives from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries, including Wolfram of Eschenbachs Parzival and the epic Song of the Nibelungs, and sets them in their global contextProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019058509 | ISBN 9780814214251 (cloth) | ISBN 0814214258 (cloth) | ISBN 9780814278017 (ebook) | ISBN 0814278019 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: German literatureMiddle High German, 1050 1500 History and criticismTheory, etc. | Literature, MedievalHistory and criticismTheory, etc. | Agent (Philosophy) in literature. | Material culture in literature. | Object (Philosophy) in literature.

Classification: LCC PT .B 2020 | DDC ./dc

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ 2019058509

Cover design by Jordan Wannemacher

Type set in Adobe Minion Pro

For Claire, Jean, and Martha

CONTENTS

FIGURES

COLOR PLATES

It is a pleasure to acknowledge some of the many people, institutions, and things that have supported me in writing this book. Most of the text was written during a Leverhulme Research Fellowship generously awarded to me by the Leverhulme Trust, and during a research leave in Berlin made possible by the School of Modern Languages at the University of St Andrews, especially my then Head of School, Prof. Will Fowler. Both institutions also kindly contributed to the publication costs. Thank you.

I would also like to thank my colleagues who invited me to present some of this work in advance: Leah Clark, Katherine Wilson, Nadia Kiwan, Tara Beaney, Carolyn Dinshaw, Martha Rust, Jamie Staples, Kathryn Starkey, Elaine Treharne, Sarah Bowden, Manfred Eikelmann, Stephen Mossman, Michael Stolz, Astrid Lembke, Andreas Kra, Michael Standke, Tim Greenwood, Vicky Turner, Silvia Reuvekamp, Elizabeth Andersen, Nicola McLelland, Ricarda Bauschke, and, at particularly significant early stages of my project, Anna Mhlherr, Heike Sahm, Herbert Kalthoff, Torsten Cress, Tobias Rhl, Jim Simpson, and Amy Wygant. My discussions with audiences and co-presenters have had a huge influence on this book. I have also been stimulated by engaging with museum collections, especially at the Burrell Collection in Glasgow and at Glasgow Life, and by discussions with artists and curators, in particular Michaela Zoeschg, Rachel King, Jo Meacock, and Christine Borland.

Special thanks to Frances Andrews, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Louise dArcens, Carolyn Dinshaw, Beth Robertson, and Gene Rogers for their steadfast and eloquent support of my work. Eileen Joy, the BABEL working group, and the journal postmedieval first made me think of this project, shaped its development, and opened up my horizon for the possibilities for medieval studies, as well as allowing me to publish some early work.

Thank you to my friends who, at the early stages of my research, were outraged and demanded better when I gave bad explanations of the agency of things (of course the chair cannot act, Chris Jones! of course the smartphone can act, Tamsin Mather! lets make the internet of things happen, Oliver Haffenden!).

For important discussions: thanks to Tom Clarke, Thomas Meinecke, Claudia Ott, Andrew Prescott, Falk Quenstedt, Karl Steel, my reading group friends Jane Burns, Elodie Lagt, Dora Osborne, Ann Marie Rasmussen, and Tom Smith, and my students, especially in the Mediaeval Things modules, who have all given me numerous ideas, helped me clarify my thinking, and reminded me of this projects value.

For reading and commenting on some of my chapters: Jeff Ashcroft, Sophie Marshall, James Paz, Paul Strohm, Claire Whitehead, my Society for Medieval Feminist Scholarship reading group buddies Jessica Hines and Erik Wade, and The Ohio State University Presss anonymous reviewers.

This book was written in various libraries and homes. I am grateful to the humans and non-humans in them for giving me the peace, pleasure, knowledge, and inspiration I needed.

For fun and listening to my many crazy medieval stories, Jean and Martha Whitehead.

For love, laughter, support, and happiness, Claire Whitehead.

Thank you and danke!

What does medieval literature look like from the perspective not of its knights and ladies, its heroines and saints, but of its treasures and castles, coins and chalices, its clothes and armor? And what does this tell us about the way writers and audiences perceived the material world and its agency? Can the stories that people told about material things in the centuries we now call the Middle Ages inspire our stories, and our understanding of objects? These are the questions that animate this book, bringing together contemporary theoretical concerns and medieval narratives.

Material things and the non-human are currently pushing themselves into the center of academic and public attention. Climate change, digitalization, and globalization contribute to the widespread sense that there is a new Copernican revolution under way, that a new age of the Anthropocene has begun. Humankind is recognized as this periods most dominant geological force, but in this sense paradoxically no different from inanimate geological forces such as volcanoes or ice caps, and can no longer be considered the center of the universe. Two pervasive modern habits of thought are challenged in this emerging new worldview: our habitual belief in human exceptionalitythat is, the idea that humans are set apart from all other species by consciousness, language, agency, a soul, mind, or free willand our habitual anthropocentrismthat is, the focus on humans and human activity rather than the wider ecosystem. While there is much anxiety about such change, many academics and activists also point out the positive potential of dethroning the human. They aim to rethink in particular the notion that only humans can be subjects who have agency and can transcend the material world, while the material world is limited to the status of a passive object. Ecocritics such as Serenella Iovino, Serpil Oppermann, and Jeffrey Jerome Cohen have suggested that by concentrating on a non-human time scale and non-human agents, new perspectives on the ecological crisis, and new ideas for solving it, can emerge.

Such new materialist or posthumanist approaches are often viewed with suspicion by critical theorists and literary critics who see the renewed attention paid to the material world either as a reactionary escape from critical theory or as a return to positivism and to a realm that is imagined as somehow pregiven and outside language. Others see it by contrast as too theoretical, as a turn away from political engagement. These are valid concerns for much current scholarship on materiality, and for some critical theory after the material turn. Most thinkers in the traditions of ecocriticism, feminism, sociology, and philosophy mentioned above, however, ask deeply theoretical and deeply political questions about the nature and agency of matter, things, and humanity. Feminist posthumanist thinkers such as Barad and Haraway, in particular, make the argument that language and material reality, which have been treated as separate realms in modern western philosophical thought, are points on a spectrum rather than opposites, processes rather than results. As well as drawing attention to the inequalities of associating non-male, non-white, non-Christian, non-straight humans with bodies and matter rather than with language and mind, these theorists explore the emancipatory and positive potential for underprivileged humans of reclaiming materiality. The present study broadly aligns itself with such posthumanist and new materialist work on non-human things insofar as it attempts to rethink agency and materiality, without compromising on political engagement.

Next page