To Dorothy

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

This is book six in the Irish Country series, books that wouldnt exist but for the unflagging efforts of some very special people.

In North America

Simon Hally, who started it all.

Natalia Aponte, my agent, who acquired the first book for Forge, persuaded Tom Doherty to publish it and its successors, and who is a never failing support when the muse goes on vacation.

Rosie and Jessica Buckman, foreign rights agents. Their successes in placing my works lead me to believe they could persuade the Innu people of Nitassinan in Arctic Canada to buy blocks of ice.

Carolyn Bateman, my personal editor. Together we have been through the rough and smooth of nine books over fifteen years and are now working on book ten. Whenever my bicycle wobbles off course, she gently, but oh so firmly, puts me back on track.

Paul Stevens, my editor at Forge, for whom no question is ever stupid, no request too much trouble, and who likes Mrs. Kincaids recipes.

Irene Gallo and the Art Department at Forge, and Gregory Manchess, the artist who renders the jacket art. No author could ask for a more sympathetic group of creative people who will accept authorial intrusion without complaint. Their efforts have made the Irish Country series instantly recognisable because the covers always reflect the contents of the work.

Patty Garcia and Alexis Saarela from Publicity. Much of their work goes unheralded, but without them, no one would know the books are out there.

Christina MacDonald, whose sharp eye in copy edit has rescued this book from its authors very personal style of touch typing and his persistent belief that George Gershwin wrote Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.

Old men forget. I wish I could remember who said that. So do old physicians. Once more, Doctors Thomas Baskett and Linda Vickars have freely provided their expertise on matters respectively obstetrical and haematological.

In The Republic of Ireland

Much of A Dublin Student Doctor was written while we were living in Ireland. My efforts to strive for authenticity would have been feeble indeed, but for the untiring support of:

The Librarian of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland,

The Librarian of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland,

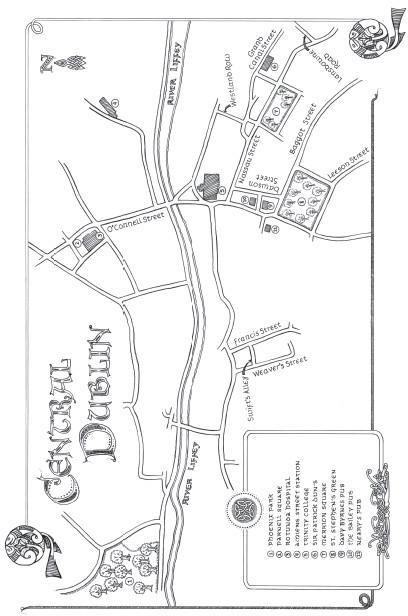

The Librarian of the Rotunda Hospital and her staff.

My limitless questions and requests for photocopying were dealt with by all of these experts with the grace of nobles and the patience of Job.

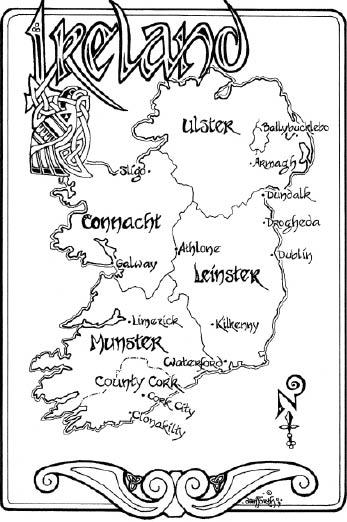

The people of Cootehall, County Roscommon, and Dublin City who allowed an Ulsterman to renew his feel for the life and the speech patterns in the Republics rural and metropolitan regions.

To you all, Doctor Fingal Flahertie OReilly and I offer our most sincere thanks.

C ONTENTS

Its a Long, Long Road from Which There Is No Return

Fingal Flahertie OReilly, Doctor Fingal Flahertie OReilly, edged the long-bonnetted Rover out of the car park. Lord Jasus, he remarked, but this twenty-fourth day of April in the year of our Lord 1965 has been one for the book of lifetime memories. He smiled at Kitty OHallorhan in the passengers seat. For all kinds of reasons, he said, and now that the Downpatrick Races are over, its home to Ballybucklebo. He accelerated.

Kitty yelled, Will you slow down? then said more gently, Fingal, there are pedestrians and cyclists. Id rather not see any in the ditch. The afternoon sun highlighted the amber flecks in her grey eyes. She put slim fingers on his arm.

Just for you, Kitty. He slowed and whistled Slow Boat to China. All right in the back?

Fine, Fingal, said OReillys assistant, young Doctor Barry Laverty.

Grand, so. Mrs. Maureen Kinky Kincaid was OReillys housekeeper, as she had been for Doctor Flanagan. Fingal had met Kinky when hed come as an assistant to Thmas Flanagan in 1938. Shed stayed on when a thirty-seven-year-old OReilly returned in 1946 from his service in the Second World War and bought the general practice from Doctor Flanagans estate.

Theyd been a good nineteen years, he thought as he put the car into a tight bend between two rows of ancient elms. So had his years as a medical student at Dublins Trinity College in the 30s.

Jasus thundering Murphy. OReilly stamped on the brake. The Rover shuddered to a halt five yards from a man standing waving his arms.

OReillys bushy eyebrows met. He could feel his temper rise and the tip of his bent nose blanch. Everyone all right? he roared, and was relieved to hear a chorus of reassurance. He hurled his door open and stamped up the road. What in the blue bloody blazes are you doing standing there waving your arms like an out-of-kilter semaphore? I could have squashed you flatter than a flaming flounder-fish.

The stranger wore Wellington boots, moleskin trousers, and a hacking jacket. He had a russet beard, a squint, and was no more than five foot two. OReilly expected him at least to take a step back, apologise, but he stood his ground.

Theres no need for youse til be losing the bap, so theres not. Theres been an accident, and Im here to stop big buggers like youse driving into it, so I am. See for yourself. He pointed to a knot of people and the slowly rotating rear wheel of a motorbike that lay on its side.

Accident? said OReilly. He spun on his heel. Barry. Grab my bag and come here. He turned back. Im Doctor OReilly. Doctor Lavertys coming.

Doctor? Thank God for that, sir. A motorcyclist took a purler on an oil slick, you know. Somebodys gone for the ambulance and police.

Here you are. Barry handed OReilly his bag. Whats up?

Motorbike accident. He spoke to the short man. Youd be safer back down the road where drivers can see you before theyre on top of you.

Right enough. Ill go, sir. He started walking.

OReilly yelled, Kitty. Kinky. Theres been an accident. Stay with the car. Kitty would have the wit to pull the car over to the verge. Come on, Barry. OReilly marched straight to the little crowd. Time to use the voice that could be heard over a gale when hed served on the battleship HMS Warspite. Were doctors. Let us through.

Ruddy-cheeked country faces turned. Murmuring people shuffled aside and a path opened.

A motorbike lay on the road, an exclamation mark at the end of two long black scrawls of rubber. The engine ticked and the stink of oil and burnt tyre hung over the smell of ploughed earth from a field and the almond scent of whin flowers.

A middle-aged woman knelt beside the rider. The victims head was turned away from OReilly, but there could only be one owner of that red thatch. A duncher lay a few yards away. It irritated OReilly that Ulstermen wouldnt wear crash helmets but favoured cloth caps, worn with the peak at the back.

He knelt beside the woman and set his bag on the ground. Hes unconscious, hes breathing regular, his airways clear, his pulse is eighty and regular, and hes not bleeding. There dont seem to be any bones broken, she said, and added, Im a first-aider, you know.

Thank you, Mrs.?

Meehan. Rosie Meehan.

OReilly smiled at her. Donal? Donal? he said gently. Fifteen minutes ago hed seen Ballybucklebos arch schemer, Donal Donnelly, riding the motorbike from the car park.

No reply.

OReilly grabbed the mans wrist. Good. Mrs. Meehan was right; the pulse was strong and regular. Donal, he said more loudly, Donal.

Next page