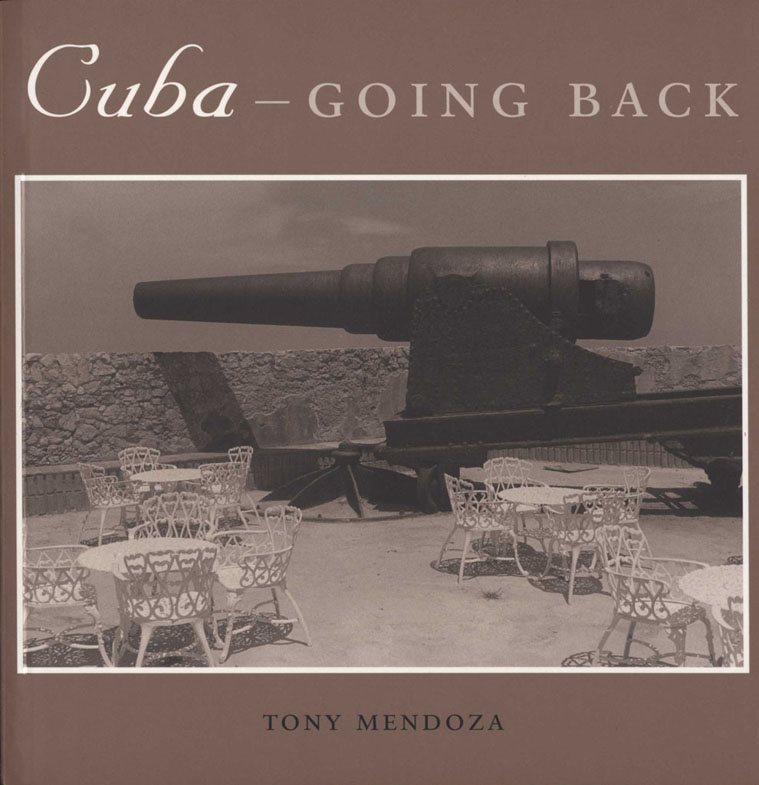

Cuba GOING BACK

By TONY MENDOZA

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

Austin

Photographs 1997 by Tony Mendoza

Text copyright 1999 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Second Printing, 2000

Designed by Ellen McKie

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Mendoza, Tony, 1941

Cuba : going back / by Tony Mendoza. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-292-75232-6 (cloth : alk. paper).

ISBN 0-292-75233-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. CubaDescription and travel. 2. CubaPictorial works. 3. CubaSocial life and customs1959 4. CubaSocial conditions1959 5. Mendoza, Tony, 1941 JourneysCuba. I. Title.

F1765.3.M46 1999

917.219104'64dc21 98-51938

ISBN 978-0-292-78102-3 (library e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-78815-2 (individual e-book)

DOI 10.7560/752320

For

Carmen, who loves all things Cuban as much as I do.

For

my father, who would have been proud of this book.

For

that wonderful institution, the university sabbatical, which made this book possible.

CONTENTS

CubaGOING BACK

Royal palms in Granma Province

DURING THIRTY-SEVEN YEARS OF EXILE (and thirty-seven years of American winters), I had increasingly remembered Cuba as paradise. What I remembered and what I missed was the weather, ocean, sky, breeze, vegetation, Havana, Varadero, and the warmth and wit of the Cuban people. In August 1996 I flew to Havana, my first trip back, to confirm my memory and to satisfy my curiosity about life in socialist Cuba.

My family left Cuba during the first wave of immigration, in the summer of 1960, when Fidel Castro began the process of nationalizing all privately owned land, industries, and businesses, thus making it clear that he intended to create a socialist state. As I recall, my family was allowed to take only fifty dollars in cash and the jewelry my mother wore, while everything left behind became the property of the state. Many Cubans left that summer and during the second half of 1960around sixty thousand. Between 1960 and 1962, two hundred thousand Cubans decided that socialism was not for them and left the island.

I turned eighteen during the summer of 1960. I had just graduated from the Choate School, a private school in Connecticut, and from my somewhat warped adolescent perspective, leaving Cuba was an excellent move. American girls appealed to me immeasurably more than Cuban girls, who not only didnt drink or neck on dates but also brought along a chaperone. I liked just about everything about American culture, and I was lucky. I went directly from Cuba to a freshman year at Yale, and in 1964 I enrolled at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. By the time I graduated in 1968 with an architectural degree, I was a different person, seduced by Cambridge and the exuberance and open-mindedness of the times: the hippies, the antiwar movement, communal living, pot, acid, Rolfing, Primal Scream. Im almost embarrassed to admit this, but I still think of the sixties and early seventies as a truly wonderful period, another paradise. I expected an adventure every day.

In 1970 I joined a commune in Sommerville, a working-class community next to Cambridge, with twelve men and women. Our minimal living expenses allowed many of us to drop regular jobs and pursue other interests, mostly in the arts, and we enjoyed ourselves immensely. The year we decided not to have our traditional New Years bash, seventy-five people still showed up. I lived in the commune throughout the 1970s, and along the way I quit architecture and became an artist/photographer. During all this time, Cuba felt like a distant and not very relevant past.

That started to change when I moved to New York in 1980, hoping to give my art career a boost. The eighties werent as interesting as the sixties and seventies, so I had more time to think and reminisce. My romantic life also needed a boost. After many failed relationships with American women, I met a Cuban woman with a background very similar to my ownCarmen had studied art history in Boston and was also a veteran of the sixties in the United States. It was the first time in exile that either of us had dated another Cuban, and we were both surprised to feel so attracted, comfortable, and compatible. We moved in together. After speaking mostly English for twenty years, we rediscovered the pleasures of our native language. We purchased an alarming quantity of cassettes and CDs of old Cuban music and danced in our living room to the rhythms of Cuban boleros and danzones. Black beans and fried plantains reappeared in our kitchen, and I started wearing a guayabera, the traditional Cuban shirt.

After living in Brooklyn for a few years, we wondered what it would be like to live in a Cuban community, and in the tropics, so we moved to Miami and liked it, with reservations. We missed the museums, the art shows, the endless choice of movies and concerts we had become accustomed to in Boston and New York. We also were not used to living in the same city with a very large group of relatives, many of whom would start conversations by asking: When are you two going to get married?

Still, we liked our relatives, we loved the climate, the ocean, the wild parrots in our garden, and our late-afternoon cheese and wine picnics in Key Biscaynewhere we eventually got married in a ceremony by the sea. We would have stayed in Miami had it not been very difficult for an artist to earn a living there, and, more to the point, we needed health insurance; Carmen had a boy from her first marriage, and we both wanted another child. In 1987 I was offered a job teaching photography at Ohio State University, so our family moved to Columbus. To the tundra.

People born on islands shouldnt move to the Midwest. Every winter I had memories of Cuba that seemed to revolve around the climate. I remembered Varadero Beach, where my entire family on my mothers side spent the three summer months at my grandfathers house. I especially remembered the porch overlooking the ocean. I ate breakfast there every morning, always on the lookout for the large fishsharks, barracudas, tarponsthat glided close to the surf in the early morning to feed on sardines. After a morning of fishing and waterskiing, I would return to the porch. There was a comfortable, soft couch there, where I stretched out after lunch and napped. I can still feel the sea breeze on my face and hear the hypnotic sounds of the surf. I wanted to see that porch again and go swimming in front of the house.

When I turned fifty my Cuba nostalgia started to get out of hand. I wrote a series of coming-of-age fictional stories about a fourteen-year-old boy called Tony who lived in Havana in 1954. I would listen obsessively to CDs of Lucho Gatica and Rolando Laserie, the singers who were popular on the Cuban radio during the 1950s. Every time I saw pictures of Havana in photography books shot by European journalists, I would strain to see if I recognized the streets, the parks, the buildings in the background. I remembered Havana as an exceptionally beautiful city, but in my youth I had been unconcerned with beauty and had no frame of reference. Now I knew better, and I wanted to see Havana again. I especially wanted to see the house where I grew up and the huge mango trees in the garden, where I must have killed a thousand sparrows with my BB gun (which I regret now!).