Willoughby S. Hundley III, MD

Copyright 2022 by Willoughby S. Hundley III, MD

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or transmitted in any form or manner, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the express written permission of the copyright owner except for the use of brief quotations in a book review or other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

County Medical Examiner | 1

T he beep-beep-beep-beep abruptly wakened Dr. Obie Hardy from a deep, restful sleep. He fumbled on the bed stand to locate and silence the disturbance. Straining in the dark, he read the digits against the glowing green display on his beeper: 9-1-1. This was not the usual four-digit hospital extension he was accustomed to. The clock displayed 3:10.

This is Dr. Hardy, he said after calling the emergency number.

We need a medical examiner, announced the dispatcher.

Obie Hardy groaned. He was one of the six physicians in Mecklenburg County who performed this service. Since he hadnt had a case in two months, he was overdue. He hurriedly put on some khaki pants and a T-shirt and slipped his bare feet into a pair of Topsiders by the back door.

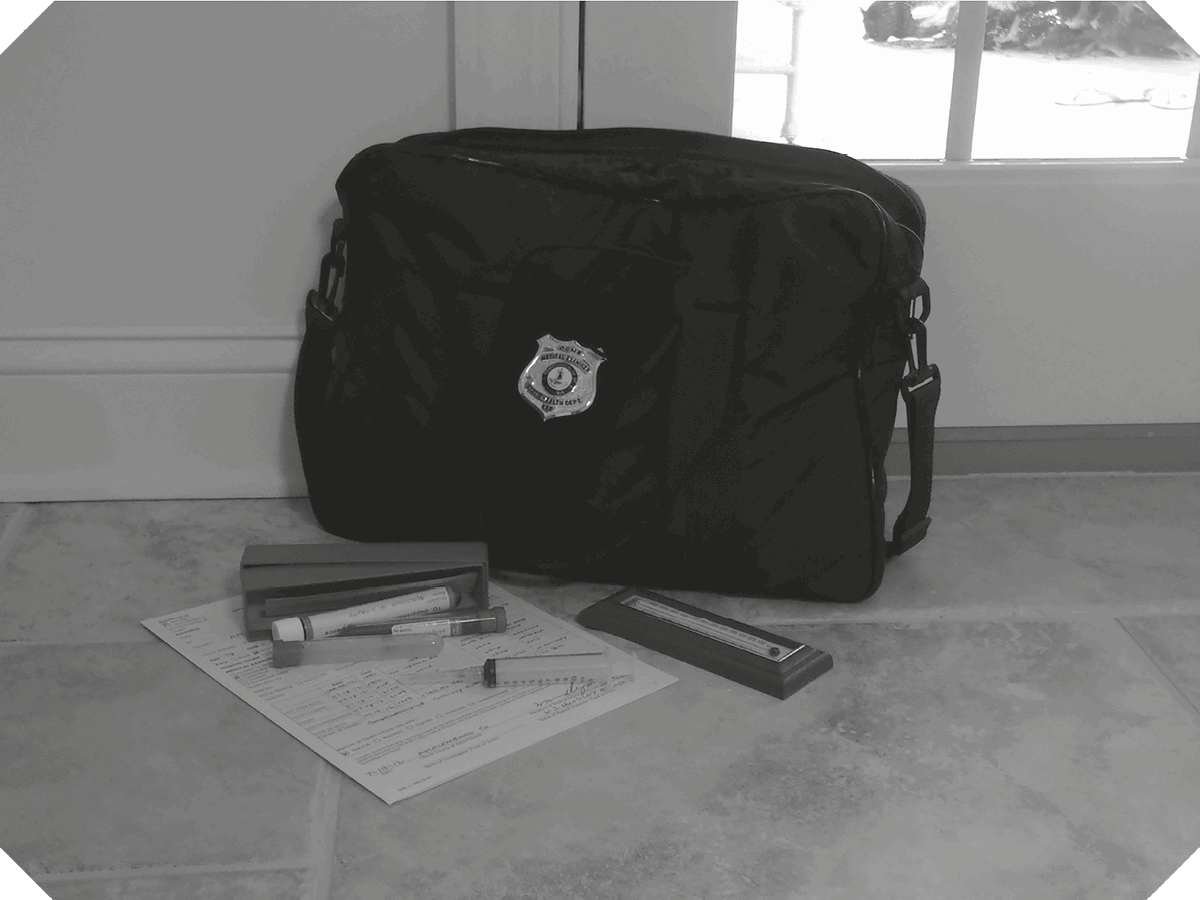

The bitter cold night air slapped him awake as he stepped out of the door and scampered into his chilled Jeep Cherokee. He made a quick stop at his oce to retrieve the four-page CME-1 report form, a pen, and a clipboard. The dispatcher had given him a house address, so it wouldnt be a highway fatality. Dr. Hardy expected it would be the routinean elderly man found dead at home from natural causes, with no recent medical care. But as he traveled down Old Cox Road, the pulsating glow of ashing red and blue lights above the horizon ahead told him that this might be more involved.

An overweight deputy approached the doctor as he closed the drivers door of his Jeep. The rst ones over here, he said, motioning toward the door of a mobile home.

The rst one? asked Hardy.

Yeah. A murder-suicide.

Obie Hardy sighed. I only brought one form. As the frigid February air owed over his ankles, he wished he had brought some socks as well as a second medical examiners form.

Anna Thacker lay facing up about twenty feet from the front door of the mobile home. Her eyes were open, eerily staring at the sky. A dark red puddle of blood extended from behind her head, and an open wound was obvious on her right temple. In the center of the blood pool, a pale yellow fragment of bone the size of a quarter caught Obies eye. He could feel the warmth of her body against the cold night as he placed his thermometer under her right arm. It was a plastic, rectangular outdoor thermometer covered by a ziplock bag. The technique was backwoods-like, but by the time Obie Hardy completed his body survey, he had an axillary temperature reading of 76 degrees to record. In unwitnessed deaths, heat loss charts could help approximate the time of death.

We gure she was shot about 2:33, stated Johnson, the plump deputy, still standing by Dr. Hardy. The call came in at 2:35. We were on the scene in eight minutes, at 2:43. Deputy Harris and I found him in the yard, pacing back and forth, shaking his head. We asked him to drop his weapon, and he just stopped and put it to his head. We werent here two minutes before he shot himself.

Obie began focusing on the second body, Mohammed Thacker. He paced o the distance from the rst body as he approached Mohammed, who lay in the opposite corner of the yard. The spotlight from the police cruiser harshly shadowed the body, also facing up, with a vacuous look in his eyes. A handgun was near his outstretched right arm.

So you witnessed this shooting?

Yeah. Me and Wayne Harris.

Has anyone taken photos? asked Dr. Hardy.

Yeah. Investigator Bruce Duer took em. We got plenty. Johnson gestured toward the mobile home. Dr. Hardy saw through the storm glass door the silhouette of an ocer with a camera, taking statements from the people inside.

Obie moved the outstretched left arm alongside the torso, putting the bagged thermometer under the dead mans shirt, in the armpit. Now tremulous, Obies rubber-gloved ngers had become cold and numb in the bitter night. Ink was reluctant to ow from his pen, which was making note- taking awkward. As he leaned over the body, his nose nearly dripped water from the cold air; he snied frequently.

The entrance wound was clearly identiable on the right temple, and Obie estimated it was two centimeters in size. The exit wound involved about one-fourth of the skull on the left, the broken bones palpable under the doctors ngers. A puddle of dark burgundy blood covered the ground under the head, and globs of tan and grayish gelatinous brain remnants oated in the sanguine sea. Chunks of pale yellow bone fragments were scattered about.

Obie recorded the demographics from the drivers license data that Ocer Johnson had pulled from the DMV. He scanned his only CME-1 form, making sure he had collected the required information for completing the second form, still at his oce. Last, he retrieved the thermometer, noting the 78 degree reading.

Let me call the Richmond oce, he said. Retreating to his Jeep, he called the answering service on his mobile bag phone and let his vehicle run to warm up while he waited for the Richmond central district to return his call. Hardy depended on the cumbersome bag phone because service in his rural county was spotty and his roof magnet antenna aorded him better range. He waited for ten minutes, shivering and cold in just a jacket and no socks, trying to ll in the empty blanks on the CME-1 form. The idling Jeep seemed to share Dr. Hardys shivering. Finally, the oce called and accepted both the victims for autopsy, meaning Hardy did not have to collect toxicology and blood samples, a welcome break. The vehicle was now warm and, backing out of the driveway, he waved to Ocer Duer, who had emerged from the home.

He drove to his oce to complete the second form on Mohammed Thacker and fax both to Richmond, making them available for the morning postmortem exams. At 4:40 a.m., he returned to bed to get an hour of sleepless rest before the workday began. When he arose the second time, his body was warmed again even if unrested. The rst clothing he donned was a pair of socks.

Dr. Hardy attended his hospitalized patients at the local community hospital each morning. At age fty, this daily task was a well-established routine, seven days a week. This morning was no exception, so he completed his rounds at the hospital and then headed for his oce in Boydton, the Mecklenburg county seat. His wife, Lucy, was the nurse manager in his oce, and she greeted him as he arrived. After fteen years as a rural physicians wife, she was accustomed to having him called out during the night.