Contents

Guide

Page List

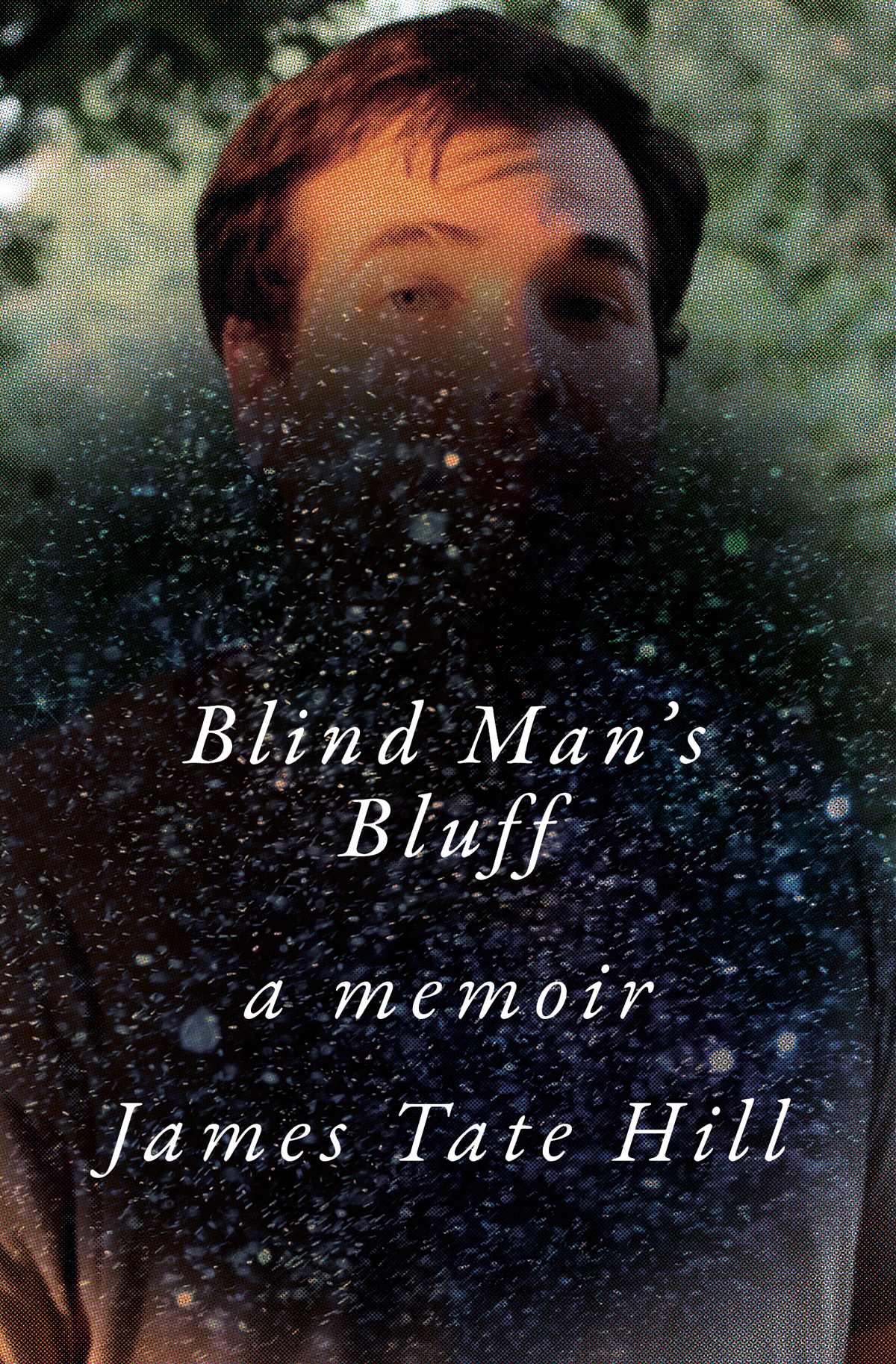

ALSO BY JAMES TATE HILL

Academy Gothic

BLIND

MANS

BLUFF

A Memoir

JAMES

TATE HILL

For my parents

and for Lori

Writers, unlike most people, tell their best lies when they are alone.

Michael Chabon, Wonder Boys

CONTENTS

The events depicted in these pages are based on my own recollections. Conversations have been reconstructed to the best of my abilities, and certain names and identifying characteristics have been changed. In a few cases, incidents have been compressed to accommodate the narrative flow.

BLIND

MANS

BLUFF

ITS FULL DARK WHEN we reach Nashville in December. Mom reads me the names of stores and restaurants as she drives, trying her best to feign excitement.

Looks like youve got an Olive Garden, she says.

The jewel of my new neighborhood is a mall with a JCPenney, a Baptist church, and a bookstore that only sells remaindered books. Even if I want to leave my apartment, the lack of sidewalks means navigating around a four-lane highway. Never leaving the apartment sounds like a better idea.

I call my wife, Meredith, to say were close. Shes making mulled wine with a bottle of our wedding Cabernet.

Shouldnt we save that for a special occasion? I ask.

You moving here isnt a special occasion?

Shortly after accepting my marriage proposal, Meredith took an editing job that paid twice what I earned as an adjunct instructor of composition. We married in September and lived apart while I taught one final semester in North Carolina.

I dont really like mulled wine, I say.

Does your mom?

I dont think so, I say, not bothering to check with her.

My wife is all smiles when she answers the door. She hugs her mother-in-law while I carry boxes to the corner of the living room. I used to envy Merediths outgoing personality. In light of recent events, I no longer trust her good moods.

I cant believe we got married, my wife told me one night in early November, two months after we were married.

What?

She repeated what she had said.

What are you talking about? Where is this coming from?

She had trouble explaining.

I hung up on her. Moments later, unsatisfied by the fecklessness of hanging up on a cordless phone, I called her back.

What are you going to do when you get here? she asked.

What do you mean? I had no clue where this conversation was coming from. Recently our calls had been a little strained. We started to miss a day here and there. I blamed my frustration with how little progress I had made on the new novel. After every publisher to whom my agent sent my first novel had passed, my confidence in my writing wasnt at an all-time high.

When we met in graduate school, Merediths and my shared passion for writing had felt like a belief in the same god. Despite this compatibility, we rarely talked to each other about our work. Opening up to her about the wall I had hit seemed like a positive development.

We never fixed anything, she said.

On TV, Darrell Hammond was doing Bill Clinton in a Saturday Night Live rerun. I had muted it before calling, but left it on, the screens flicker the only light inside the black tunnel in which I unexpectedly found myself. I stared in the TVs direction, but it was too far, five feet away, for my eyes to discern more than movement.

In an email the next day, Meredith apologized for calling after drinking most of a bottle of wine. Her apology didnt extend to the content of her words, only how bluntly she had said them. I will not, she elaborated days later, be complicit in your lie.

I wasnt sure which word hurt more, lie or the B-word embedded so thornily in the next line. Blindness. Your blindness. I will not help you hide your blindness from the world. She had never used that word around me before. If she knew how deeply it wounded me, would she have avoided it or moved it from quiver to bow years ago?

Its better and worse than you might imagine. This is what Id like to tell people who ask about my eyesight. What most people want to know is what I see when I look at them, and the short answer is this: I dont see what I look directly at. If I look up or to the side, I can see something, and this usually fends off further questions. This answer allows people to imagine, however erroneously, that my blind spots are smudges on the center of a mirror from which I can escape by looking elsewhere on the mirror. Lies of omission werent ones I hastened to correct.

Instead of a smudge, picture a kaleidoscope. Borderless shapes fall against each other, microscopic organisms, a time-lapsed photograph of a distant galaxy. Dull colors flicker and swirl: mustard yellow, pale green, magenta.

That would drive me crazy, a friend once said when I described my blind spots for her.

The most frequent compliment heard by people with a disability is I could never do what you do, but everyone knows how to adapt. When its cold outside, we put on a coat. When it rains, we grab an umbrella. A road ends, so we turn left, turn right, turn around. We adapt because its all we can do when we cannot change our situation.

I can still see out of the corners of my eyes, but heres the thing about peripheral vision: The quality of what you see isnt the same as what you see head-on. Imagine a movie filmed with only extras, a meal cooked using nothing but herbs and a dash of salt, a sentence constructed only of metaphors. To see something in your peripheral vision with any acuity, it has to be quite large. On top of this, my periphery isnt unaffected by the blind spots.

Looking directly into a mirror, I am not without a face. My kaleidoscopic clouds permit enough light to see pronounced contrasts like my eyes, nostrils, the crease where my lips meet. Of the many mundane abilities my remaining sight permits me, I am especially grateful for the ability to feign eye contact, if not always as convincingly as I would prefer. The closer someones face and the better the lighting, the more easily I can keep track of the shadows between nose and forehead. A few inches from the mirror, I can gauge with some accuracy if all the coffee Ive consumed has stained my teeth, style my hair, ponder the accuracy of a girl who told me when I was twenty that I kind of looked like Ben Affleck, which might or might not have compelled me to defend the actors sometimes-problematic career choices for the next two decades.

When our emails finally reverted back to phone calls after our argument, I asked the only question that seemed to matter: Should I move to Nashville? I had already given notice to my employer. For the past four months, I had slept on an air mattress and eaten off chipped plates I planned to donate to Goodwill.

Merediths hesitation felt like an answer. She asked what I thought.

I think your answer is more important than mine.

Another pause. If you dont, this doesnt have much of a chance, does it?

That isnt a yes.

Then yes.

It wasnt the starry tone with which shed uttered that word when I slid an engagement ring around her finger, but it was better than no.

Meredith and I barely speak while we finish unloading the car. A Christmas cartoon blares on the TV. Meredith asks Mom if she wants to try the mulled wine. Theres also pumpkin bread.

I step into the bathroom with my coat still on. The bathroom has two doors, one leading to the hall and one to the bedroom. I lock both of them and bury my face in a bath towel. After a few minutes, I pull myself together. How apparent will it be that I have been crying? I study the blurry face in the mirror. If I stare at things long enough, I like to tell people, they eventually come into focus, but this is not true.