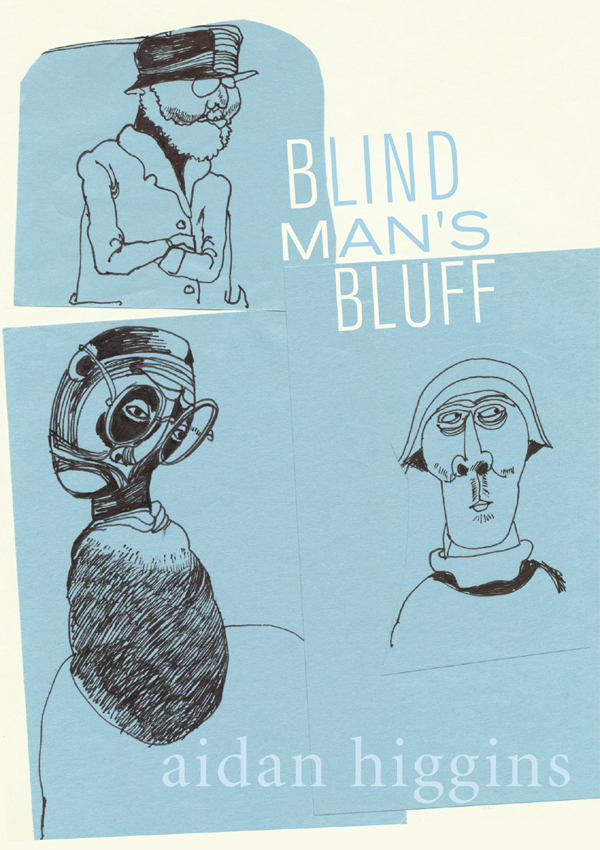

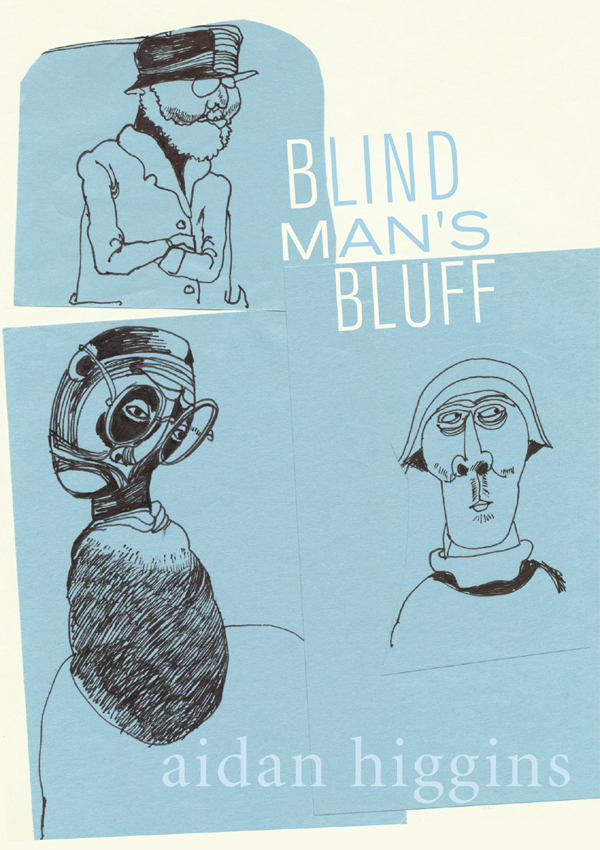

BLIND

MANS

BLUFF

AIDAN HIGGINS

Felo de Se

Langrishe, Go Down

Images of Africa

Balcony of Europe

Scenes from a Receding Past

Asylum & Other Stories

Bornholm Night-Ferry

Helsingor Station & Other Departures

Ronda Gorge & Other Precipices

Lions of the Grunewald

Flotsam & Jetsam

As I was Riding down Duval Boulevard with Pete La Salle

A Bestiary

Windy Arbours

Darkling Plain: Texts for the Air

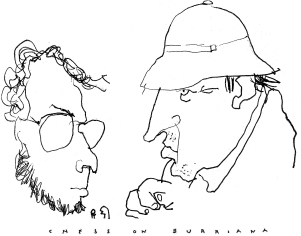

ABOUT AIDAN HIGGINS

Aidan Higgins: The Fragility of Form

For the Semi-Blind

Compiled with the Aid of Neil Donnelly,

Matthew Geden, and Alannah Hopkin.

Part the diamonds and youll find slugs meat.

Djuna Barnes

CONTENTS

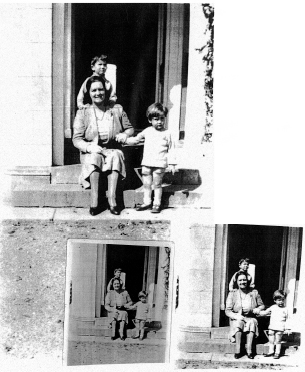

Nothing was ever as familiar as the mile-long road from our front gate (two lodges, seventy-two acres, grazing for horses or cows) to the village a mile off. It seemed forever in existence and could never change. At the corner was Bradys farm. Next was the Collegiate Girls School. The Protestant orphans seemed to spend most of their free time in the hockey field instead of the classroom. They were taken crocodile-fashion in double file for walks at regular intervals, their teachers striding behind. I was acutely embarrassed when I had to pass this file of chattering girls, and blushed to the roots of my hair.

One day came a strange disruption of the ordinary. As usual I was being pushed in my black-hooded pram, that most funereal looking thing, into the village and found water up to the approaches of Marlay Abbey, then occupied by nuns. The village was flooded, the Liffey had overflowed its banks, the bridge with five arches was under water. No one was about. We had to turn back. What must the deluge have been like? It was a day of prodigious happenings, never to be repeated. Nothing predictable was to be expected. It was to become a time of stupendous occasions. First the flood, then the death of the postman and old Jem Brady.

For days it was noticed that he behaved peculiarly, he wasnt himself. Then one morning his bed was empty.

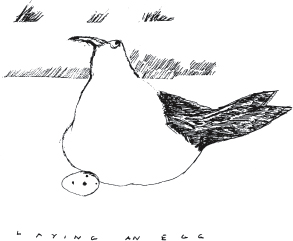

Years went by and Papa Hemingway hobnobbing with Castro in Cuba had tamed an owl for which he could find no adequate pet name. Papa was a great inventor of cruel nicknames, called Marlene Dietrich the Kraut. Not finding a suitable pet name for the owl, he called it OWL, wise old owl, and this suited the bird as no other name could. No other word would do.

You might like to know how it all began, what induced me to write in the first place. Why, where everyone began, with ones mother, herself a voracious reader, with access to banned books. The light romance, Without My Cloak, and Brinsely McNamaras The Valley of the Squinting Windows that my wife wittily renamed The Valley of the Squinting Widows.

My mother put a pencil in my hand and pointed at the cat that was watching us intensely, and said, Write down CAT for me in capital letters. She tried for days to get me to write CAT but I could feel no affinity between the observant dumb creature and the word CAT. My mother tried Hat, Fat, Mat, Bat, all to no avail, until one day the miracle occurred. Animate and inanimate merged. I could now make the connection between words and a living being.

Eventually my mothers patience was rewarded, and I could read Christopher Robin and the likes. In a few years I had advanced to Robinson Crusoe and would never look back.

My mother took me to a garden sale of books in Marlay Abbey and I came away with Hemingways Green Hills of Africa, while she confined herself to Beverley Nicholss Down the Garden Path. Voracious readers will read anything, from trash to profundity.

Later, I contracted measles, which was duly passed on to my younger brother, dead before me like my two elder brothers. The curative for measles in those far-off times was to put the boy to bed for six weeks in a darkened bedroom and let him amuse himself as best he could.

My mother, the great reader, went to a Dublin book-shop and bought Hans Christian Andersen. I was away.

One day, long dreaded, we were committed to the tender care of the nuns to begin our formal education. We walked the mile from our grand mansion, mother and two bewildered lads, and were formally received at the convent by the Reverend Mother in person. Education is so important, my mother opened proceedings, and offered the Reverend Mother a Zube which was formally accepted in a gesture of good will.

Time passed and we became acclimatized to our fellow-sufferers. One day passing the girls cloakroom I saw a couple of white enamel bowls brimming with girlish blood, only recently extracted, and guessed that the visiting dentist had been at his rough and ready trade. About the playground they passed, pale and wan, handkerchiefs bloodied.

Tim Timmons it was who carried the post for Colonel Clements, and lost his life while on the job. He was a familiar sight cycling between the Clements long avenue and the village below. One day he got on his bike to catch the Birr bus coming from Dublin. The avenue terminated at the end of the hill, as did the life of the popular postman under the wheels of the six oclock bus carrying passengers home to their tea. The lads in our front lodge who liked to tell a tall tale gave us a gruesome account of the collision, the blood and guts of the unfortunate postman, the clearing up of the mess of the dead Timmy Timmons. Buckets of water flung down the hill, and yard brushes applied vigorously. Nurse kept the pram clear of the accident. It came to us as hearsay, the death of the soft-spoken postman. Not long after, while I was being conveyed down the Clements long woody avenue, a black-bird fell dead alongside the pram, gazed at with wonder by my brother, aged two, who commented Finished, the first word he ever uttered, acknowledging with wonder the world he found himself in. Nurse said it was the ghost of the dead postman. Such superstition was rife down our way. Death was always near in Celbridge.

My lackadaisical father, as lazy as they come, ran a stable for racehorses. Cabin Fire and One Down come to mind, the latter well named because he was never placed. My father was in the front yard when who should show up but our near neighbour old Jem Brady. Always garrulous, my father remarked, Yesterday I saw a rat in one of the stables. The taciturn farmer didnt reply for a while. Then he said, Of all the birds in the air, I do hate a rat. This became a stock phrase in our family.

Old Jems behaviour became odder and odder; then one morning his bed was found empty. The early riser had not risen. A vigilant guard noticed footsteps in the morning dew, leading to the quarry with its reputation of being depthless. But nothing came up in the net. One last trawl of the net before lunch and up came the drowned farmer. My young brother and I cycling to school flew past the death quarry, a bluish gas hovered over the last resting place of the good farmer, much mourned and long remembered. Thus ended childhood.

Next page