Contents

Guide

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

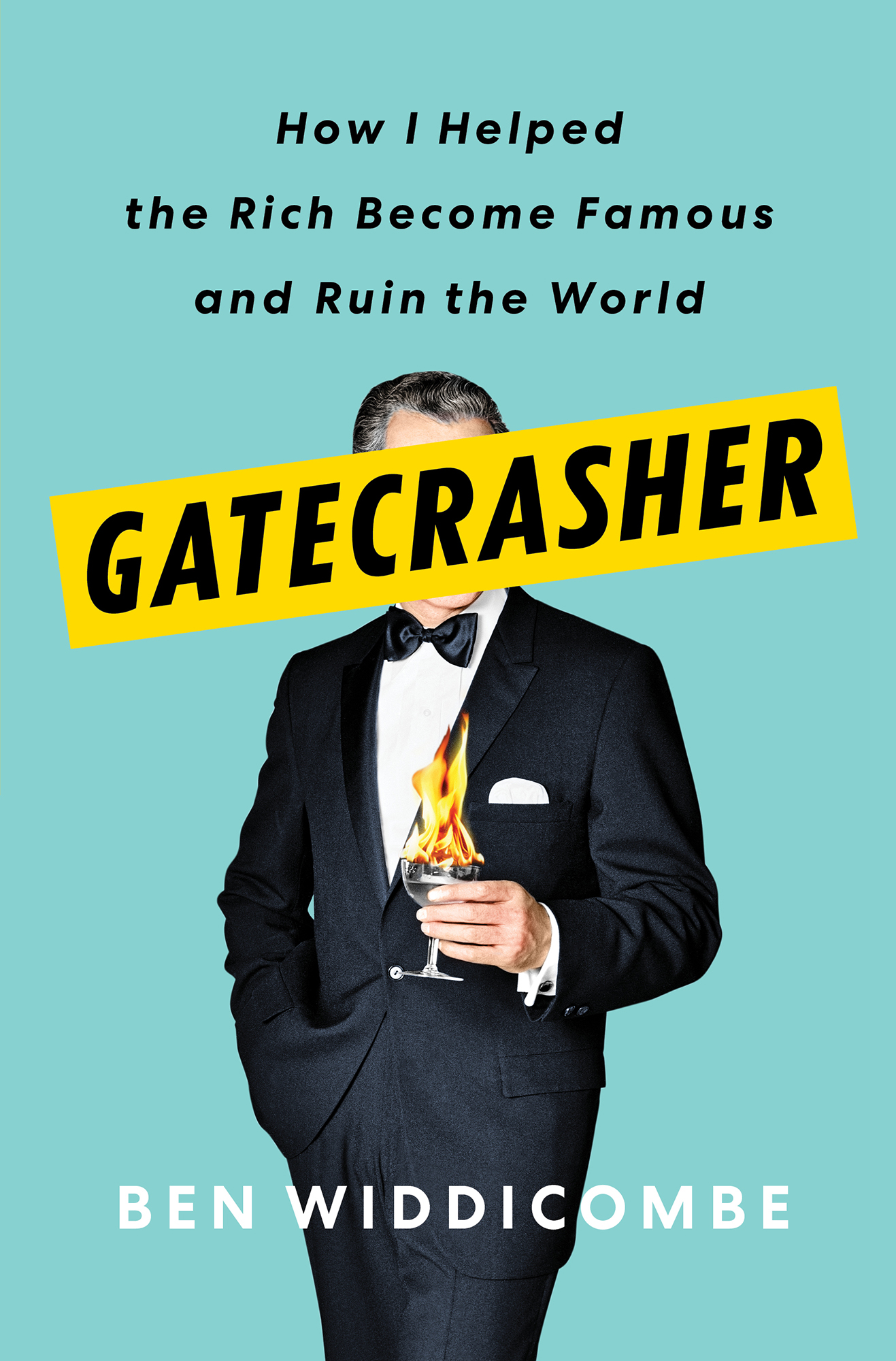

Copyright 2020 by Ben Widdicombe

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition July 2020

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Lewelin Polanco

Jacket design by Evan Gaffney

Jacket image by Akg-Images/Classicstock/H. Armstrong Roberts

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

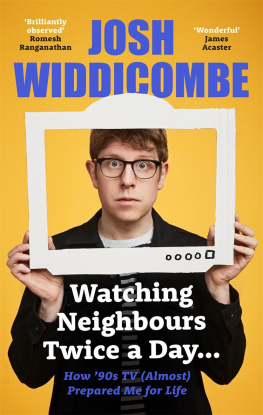

Names: Widdicombe, Ben, author.

Title: Gatecrasher : how I helped the rich become famous and ruin the world / Ben Widdicombe.

Description: First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition. | New York : Simon & Schuster, 2020. | Includes index. | Summary: A smart, gossipy, and very funny examination of celebrity culture from New Yorks premiere social columnist Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019057334 (print) | LCCN 2019057335 (ebook) | ISBN 9781982128838 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781982128845 (paperback) | ISBN 9781982128852 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Widdicombe, Ben | Gossip columnistsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC PN4874.W543 A3 2020 (print) | LCC PN4874.W543 (ebook) | DDC 070.92 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057334

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019057335

ISBN 978-1-9821-2883-8

ISBN 978-1-9821-2885-2 (ebook)

For Pam and Owen

Great minds discuss ideas; average minds discuss events; small minds discuss people.

I have always loathed that trite little quote.

Authors Note

The contents of this book are entirely organic. They have been locally sourced from the streets of New York City, including gutters, red carpets, between the seat cushions of taxicabs, endless cocktail parties, and the occasional late night in a penthouse.

All of the personal events depicted in this memoir happened as I remember them. There are no composite characters, although names were changed for a handful of individuals who are not public figures, in situations where they may have had a reasonable expectation of privacy.

Most of the anecdotes relating to public figures took place in environments where I was invited as a working journalist, with the understanding that anything I saw could be reported upon.

There are some exceptions, because that is the nature of lived life, and also I couldnt resist.

Introduction

For much of the last twenty years, going to parties in New York City has been my job. I have stalked them as a gossip writer for the New York Daily News, flown to them by helicopter for Vanity Fair and Town & Country magazines, and just now I write a column about them in the New York Times.

As writing goes, it aint Proustspeare. But I love the challenge of entering a room and uncovering the story that lies beneath the surface of each specific combination of people and place. The job requires the skills of a critic, detective, interviewer, and humorist, all balanced like a tray of mismatched glasses.

It has also provided a unique perspective on the political and cultural evolution of New York. Parties are a public performance space, and there is no better stage to watch as old taboos and pieties die out, and new ones take their place.

The broader fault lines in the culture over the past two decades are well-known. As income inequality worsened around the turn of the twenty-first century, a very few individuals amassed fortunes that exceeded any others in history. In New York, wealth once again became a public spectacle in a way not seen since the Gilded Age. But this time, something was different.

As the millennium turned, the rich began to perceive a value in publicity that previous generations of the American upper class, which modeled their reserve on old-world Protestant aristocracies, had rejected as vulgar. Publicity, after all, was a means to celebrity. And that realm belonged to the beautiful idiots who toiled in show businesslong considered an inferior caste.

But for the new ultrawealthy, money was no longer enough. Now they wanted acclaim to go along with it. So the rich rebranded themselves as famous.

I did more than just watch this phenomenon. As an agent of the media, which had an interest in pumping up the spectacle, I helped push the whole show forward. And what a show it was.

No longer, as the old maxim went, was it acceptable for the elites to have their name appear in the newspaper only three times: upon their birth, their marriage, and their death. Now nothing less than the front page would do.

But what, exactly, were they hoping to achieve?

The rich already enjoyed all the advantages that a capitalist society had to offer. So what else could they hope to gain by also being famous? The answer, quite simply, was more of everything.

In fin de sicle America, traditional twentieth-century battle lines between the lower, middle, and upper classes were being redrawn. In the twenty-first century, more citizens were concerned about the growing gulf of opportunity between the putative 99 percent of working Americans and the so-called 1 percent who were reaping benefits at the top.

Inside the snow globe of money that is New York City, however, even that view was quaint. Here, all the friction was happening within the 1 percent itself. In the arms race of the 1 vs. 0.1 vs. 0.01 percent, celebrity conferred three distinct benefits: more status, more money, and more political power.

Humans, as a hierarchical species, value the bump in status that fame provides. That renown can also be further monetized, adding to the elites key competitive advantage. And fame, which is after all a popularity contest, thrives on a parallel track to democracy.

As the liberal establishment learned to its horror in the 2010s, celebrity can be weaponized to hijack the supply of information, win elections, and control governments. Who wouldnt want to be famous with all that on the line? All you need to enjoy the spoils is to dispense with the vulnerability of shame.

Shame is a useful word, because it covers everything from modesty to social embarrassment to remorse for serious wrongdoing. I mean all of those things when I say that in twenty-first-century New York, shame has become culturally obsolete.

Many writers examine our current moment of inequality through the experience of those it hurts the most. Millions of people are in debt and face a lack of dependable employment, barriers to accessing education and health care, and vulnerability to political interests that want to restrict voting rights.

But I saw its effects from the opposite end of the spectrum. I was rubbing shoulders with the rich guys who were benefiting from the new inequalities and, in many cases, enthusiastically pushing them forward.