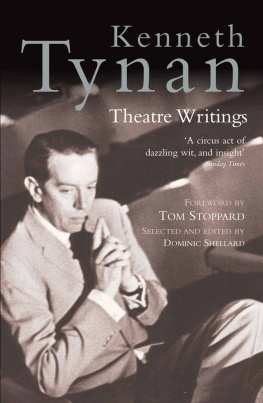

Kenneth Tynan

PROFILES

Selected and edited by Kathleen Tynan

Foreword by Simon Callow

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

To William Shawn

Foreword

Like many people of my age, I did my formative theatregoing not in the West End or down the Waterloo Road, still less in a repertory theatre or on the fringe, but in my own front room, with a copy of Kenneth Tynans Curtains in my hands. Its chance discovery on a bookstall was the epiphany that revealed to me the existence of a fabled, exotic, distant world, that became my goal: the world of theatre. Reading and re-reading the reviews, I felt that I had seen the productions so enticingly described; that I had been there when Oliviers entrance as Titus had ushered us into the presence of the man who is, pound for pound, our greatest living actor; had seen Orson Welless false nose part company with his real one as he became unlike Oliviers Hamlet (a man who could not make up his mind) a man who could not make up his nose. Visits to the theatre itself to the Old Vic, for instance, in its grey final days before the National Theatre moved in, or the dull West End of the early sixties were poor competition for the productions I had seen in Tynans pages. Tynans theatre was a place of glamour, intellectual glamour, above all, a place where ideas were thrillingly incarnated by exceptional human beings. It was not until Oliviers first season at the Vic in 1963 that I saw with my own eyes what he had been talking about; and it was Tynan of course, who, as Literary Manager, was part architect of that thrilling succession of performances and productions.

At the heart of his work as a critic was a sense of the individual achievement: the writers, the directors, and, supremely, the actors. His reviews have less to do with judgement than with evocation; the element of performance was the crucial one for him. He writes about acting and the theatre as if he were a sports commentator: knowing the form, following every turn of the game, submitting to the physical excitement of it. Roaring with the crowd and dismayed at reverses, he never for a moment forgets that it is a game hes involved in. He brought the same approach to life, and it underlies all his writing: Bull Fever, obviously, but equally the profiles which throughout his career he wrote alongside his formal reviewing. They focus on people of many kinds, by no means all connected with show business; but the theme, from the earliest profile of his Oxford friend Alan Beesley to the full-scale study of Ralph Richardson, is always Life as a Performance, embodied in prose which is Writing as a Performance.

A wonderful performance it is, too. Simply as journalism, the pieces here collected are masterly. The curricula vitae are elegantly and accurately despatched, a physical portrait, often of great virtuosity, is limned, and the subjects conversation recorded. As a reporter his ear and eye are first-rate, and in the use of simile he is among the funniest and most arresting writers of the century. Charles Laughton looks like a fish standing on its tail; he leaves the room with a furtive air like an absconding banker. Edith Evans acting is a succession of tremendous waves, with caps of pure fun bursting above them. He constantly surprises with unexpected conjunctions, as when, for example, he illuminates Humphrey Bogart by reference to Seneca. The longer profiles, less hectically brilliant than the sketches, are sustained examples of analysis and assessment worth more than whole volumes of biography. But beyond the sheer skill of the writing, its achievement is to make one long to have been around these people, just as one longed to have seen the productions Tynan reviewed. His love of the egregious, his sense of these great ones, is not snobbery: it is an affirmation of style as a form of courage. In this he rather resembles Cocteau; like Cocteau too he has a fine sense of the loneliness of those who invent and perform themselves. He never quite loses his posture of amused admiration, presenting himself as a dandy delicately negotiating the rim of a volcano; but his seriousness is none the less real for lacking any moral dimension. He doesnt judge, he has no lesson to draw. His philosophy is, rather, a perfumed existentialism, a flamboyant stoicism. He admires the man or woman who lives his or her life exactly as they mean to, and then picks up the bill as he did himself, weighing the pleasure of cigarettes against the price of death. In this sense, his profile of Antonio Ordez, the matador he admired above all others, is essential Tynan. Whether the chosen arena is the cabaret, the theatre, the drawing room or the corrida, the dangerous giving of oneself is the distinguishing mark of all these people.

In addition, there is his central perception of the bi-sexuality of the greatest performers. He discerns it in Bea Lillie, in Laurence Olivier, in Dietrich of course (she has sex but no particular gender) even, more surprisingly, in Sid Field: A certain girlishness seeps through the silly male bulk of the man, a certain feminine intensity on the emphatic words. Antonio Ordez is unexpectedly gentle, sweet, and slight, not the machismo figure of ignorant fantasy. Coupled with this insight is a sense, also insistently noted, of a transcendence of the physical moment. The great hedonist and prophet of the flesh discovers something quite different at the heart of many of his subjects. Bea Lillie has some attributes of the Zen master; in Garbo, there is something wanting, something cheated of fulfilment... but whatever it may be, the condition is one which could not be cured in a film studio. It has to do with her whole life. Orson Welles is a connoisseur that social, wine-wise, stomach-sensitive creature without whom art could never be understood, but by whom it is so rarely hammered out. The act of theatre, the production of art, are in the end secondary to the fact of being. The mystery of personality and the concentrated embodiment of certain essences of the human condition were, for him, sufficient contribution to the brave evasion of mortality that he celebrated. His blow-by-blow account of Oliviers Othello is an invaluable record of a great performance; but what sticks in the mind is the account of the actors heroic struggle with his own body and temperament. We know too where his priorities lie in his unforgettable assessment of one of his subjects (Welles again); A superb bravura director, a fair bravura actor and a limited bravura writer; but an incomparable bravura personality.

In the thirty years during which he wrote, the theatre and the world changed almost out of recognition, and his style modified accordingly. From the peacockery of his celebration of Beesley, through the fanfares and gavottes of his monstres sacrs pieces to the extended reflections in the essays on Louise Brooks, Tom Stoppard and Nicol Williamson, he ceased to mythologise and began instead to explore his subjects and their relationship to their world with a novelists complexity. As a stylist Tynan came less and less to live up to his middle his real name.

The group portrait of the theatrical beau monde that this collection of profiles provides, written by a fan who was also an insider, and whose enthusiasm was matched by his wit and his verbal brilliance, celebrates a vanished world of outsize personalities. It is also a glittering memorial to Tynan himself.

Simon Callow

Introduction

It comes as no surprise that a journalist who described himself as a drama critic at large... in the lives of other people chose to write profiles of highly dramatic subjects. Ken revered larger-than-life men and women of exceptional talent, craftsmanship, elegance and wit. If to these qualities was added the spice of a dangerous or eccentric temperament, he would rejoice.

Next page