THE COLLECTOR

OF LEFTOVER

SOULS

Copyright 2019 by Eliane Brum

Translation from the Portuguese copyright 2019 by Diane Grosklaus Whitty

The author and Graywolf Press have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify Graywolf Press at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund. Significant support has also been provided by Target, the McKnight Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, the Amazon Literary Partnership, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published with the support of the Ministry of Citizenship of Brazil | National Library Foundation. Obra publicada com o apoio do Ministrio da Cidadania do Brasil | Fundao Biblioteca Nacional.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-64445-005-5

Ebook ISBN 978-1-64445-104-5

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2019

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019931352

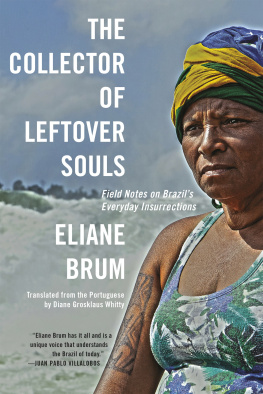

Cover design: Kapo Ng

Cover photo: Lilo Clareto, Portrait of Raimunda Gomes da Silva

For Mara, who grew into a woman,

living with me between Brazils

THE COLLECTOR

OF LEFTOVER

SOULS

INTRODUCTION: BETWEEN WORDS

Being a journalist, or being the journalist I am, means putting on the skin of the Other. And the Others skin is language, the first world we each inhabit. Everyone who lives in the words of this book lives in the Brazilian language, in the Portuguese that came along with the colonizers but was invaded by the tongues of the indigenous peoples who were already living here, in Brazils before, and by the tongues of the various African peoples who reached this land enslaved. Among the many ways they rose up was to contaminate the masters vowels and consonants. They infected the bodys language, placing curves where the Portuguese colonizers had threatened right angles, acute and cutting. They made music where earlier the whip had cracked. What I call the Brazilian languageor Brazilian Portugueseis a language of insurrections. My language and that of all the inhabitants of these pages.

These real stories told in an insubordinate tongue have for the first time been rendered in English. That this encounter will not be an act of violence but of possibility is the dream contained within this book. Its publication comes at a time when part of the world is endeavoring to build ever higher walls to keep insurgent languages from invading those who deem themselves pure, those who fear contagion from other experiences in being. In this sense, this book, which carries the insurrections of my language into English, is also what books should be, a sledgehammer for demolishing barriers. If you have opened it, this book by a Brazilian journalist, it is because you dont like walls either.

Whenever I visit an English-speaking country, I notice Brazil doesnt exist for most of you. Or exists only in the stereotype of Carnival and soccer. Favelas, butts, and violence. Lots of corruption, in recent years. In the first decade of this century, Brazil sparked global interest when Luiz Incio Lula da Silva, a metalworker who became president, performed a bit of magic, reducing poverty without touching the privileges of the wealthiest. What is called the First World really liked this magic, because it blurred the inequality explicit in the geopolitics of our planet, an inequity with deep historical roots. And it also made everyone happy without anybody having to lose anything in order to achieve a minimum level of social justice. As the following years proved, there is no magic. Since Brazil couldnt perform magic, it returned to its place in the background of the wealthy worlds imagination. Nobody gets popular by saying wealth has to be distributed so that the expendables will stop dying from hunger and bullets.

And then, in 2018, Brazil returned to the world spotlight because it elected Jair Bolsonaro, a man who defends torture and torturers; insults black people, women, and gays; and declares that minorities must vanish and that his opponents are destined for exile or jail. At the close of the 2010s, Brazil thus joined the ranks of countries that committed the contradictory act of voting down democracy by electing a defender of dictatorship. Once again, that which is unique or singular must resist between the lines, and small everyday insurrections are what make life hold steadfast in the face of a culture of death.

Brazil is a country that exists only in the plural. The Brazils. In the singular, its an impossibility. Since we are the Brazils, and not Brazil, there are also many Brazilian tongues. My challenge as a reporter is reaching these diverse tongues and converting them into written words without reducing them or the world of their telling. This is a challenge I fail at while trying.

The Brazils hold the largest part of the worlds largest tropical forest, strategic wealth in a world haunted by human-made climate change. The forest is a power at this moment when humans have quit fearing catastrophe to become the catastrophe they feared. Since 1998, I have been roaming the Amazons, listening to the stories of peoples, trees, and animals. As I write this introduction, I have been living in Altamira, a city in the Amazon forest, on the banks of the Xingu River, for a year.

This book begins with a birth in the forest and ends with a death on the periphery of Greater So Paulo, the largest urban conglomeration in Brazil and one of the worlds ten largest. At more than twenty million, its population surpasses that of countries like Portugal and the Netherlands. When Im not in the Amazons, Im in this desert of buildings where rivers are interred and covered by concrete tombs, over which we walk, always in a rush. I make my body a bridge between such diverse Brazils.

The Collector of Leftover Souls: Field Notes on Brazils Everyday Insurrections brings together stories from two distinct moments in my life as a reporter. The shorter feature reports were written in 1999. I was working that year at Zero Hora , a newspaper in far southern Brazil, the region where I was born. Every Saturday, I had a column called The Life No One Sees. In this one-page space, I wrote stories about what we usually define as ordinary people. Those who dont make the news in the paper. Or whose livesand deathsare reduced to a footnote so tiny it almost slides off the page. I wrote precisely to show there are no ordinary lives, only domesticated eyes. Eyes incapable of seeing that every life is spun from the thread of the extraordinary.