Publishing information

This seventh edition first published October 2009 by

Rough Guides Ltd , 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL

14 Local Shopping Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110017, India

Distributed by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL

Penguin Group (USA) 375 Hudson Street, NY 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Australia) 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Group (Canada) 195 Harry Walker Parkway N, Newmarket, ON, L3Y 7B3 Canada

Penguin Group (NZ) 67 Apollo Drive, Mairangi Bay, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

Cover concept by Peter Dyer.

David Cleary, Dilwyn Jenkins and Oliver Marshall

ISBN: 978-1-84836-189-8

Maps Rough Guides

No part of this e-book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

This Digital Edition published 2010. ISBN: 9781405380195

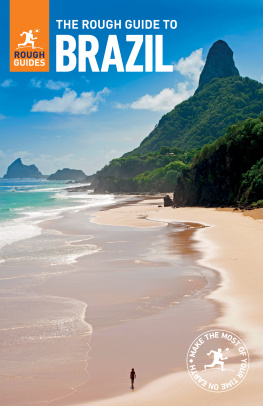

The publishers and authors have done their best to ensure the accuracy and currency of all the information in The Rough Guide to Brazil , however, they can accept no responsibility for any loss, injury, or inconvenience sustained by any traveller as a result of information or advice contained in the guide.

Introduction

Introduction to Brazil

Brazilians often say they live in a continent rather than a country. It's an excusable exaggeration. The landmass is bigger than the United States if you exclude Alaska; the journey from Recife in the east to the western border with Peru is longer than that from London to Moscow, and the distance between the northern and southern borders is about the same as that between New York and Los Angeles. Brazil has no mountains to compare with its Andean neighbours, but in every other respect it has all the scenic and cultural variety you would expect from so vast a country.

Colonial-style architecture, Olinda, Pernambuco

Despite the immense expanses of the interior, roughly two-thirds of Brazil's population live on or near the coast and well over half live in cities even in the Amazon. In Rio and So Paulo, Brazil has two of the world's great metropolises, and ten other cities have over a million inhabitants. Yet Brazil still thinks of itself as a frontier country, and certainly the deeper into the interior you go, the thinner the population becomes.

Catedral Metropolitana Nossa Senhora Aparecida, Braslia

Other South Americans regard Brazilians as a race apart, and language has a lot to do with it Brazilians understand Spanish, just about, but Spanish-speakers won't understand Portuguese. Brazilians also look different. In the extreme south German and eastern European immigration has left distinctive traces; So Paulo has the world's largest Japanese community outside Japan; slavery lies behind a large Afro-Brazilian population concentrated in Rio, Salvador and So Lus; while the Indian influence is still very visible in the Amazon. Italian and Portuguese immigration has been so great that its influence is felt across the entire country.

Brazil is a land of profound economic contradictions. Rapid post-war industrialization made it one of the world's ten largest economies by the 1990s and it is misleading to think of Brazil as a developing country; it is quickly becoming the world's leading agricultural exporter and has several home-grown multinationals competing successfully in world markets. The last decade has seen millions of Brazilians haul their way into the country's expanding middle class, and across-the-board improvements in social indicators like life expectancy and basic education. But yawning social divides are still a fact of life in Brazil. The cities are dotted with favelas, shantytowns that crowd around the skyscrapers, and there are wide regional differences , too: Brazilians talk of a "Switzerland" in the South, centred on the Rio So Paulo axis, and an "India" above it, and although this is a simplification the level of economic development does fall the further north or east you go. Brazil has enormous natural resources but their exploitation has benefited fewer than it should. Institutionalized corruption, a bloated and inefficient public sector and the reluctance of the country's middle class to do anything that might jeopardize its comfortable lifestyle are a big part of the problem. Levels of violence that would be considered a public emergency in most countries are fatalistically accepted in Brazil an average of seventeen murders per day in the city of Rio de Janeiro, for example.

Sunset over the Pantanal

These difficulties, however, don't overshadow everyday life in Brazil, and violence rarely affects tourists. It's fair to say that nowhere in the world do people enjoy themselves more most famously in the annual orgiastic celebrations of Carnaval , but reflected, too, in the lively year-round nightlife that you'll find in any decent-sized town. This national hedonism also manifests itself in Brazil's highly developed beach culture , superb music and dancing, rich regional cuisines and the most relaxed and tolerant attitude to sexuality gay and straight that you'll find anywhere in South America.

View across Rio's Lagoa towards Ipanema and Leblon

|

Fact file

By far the largest country in South America, Brazil covers nearly half the continent and is only slightly smaller than the US, with an area of just over 8.5 million square kilometres. It shares a frontier with every South American country except Chile and Ecuador.

Brazil has around 200 million inhabitants , making it the fifth most populous country in the world.

Almost ninety percent of Brazil's electricity is generated from hydropower, about six percent from fossil fuels and six percent from nuclear power. Brazil is becoming an important oil exporter, with new reserves recently discovered offshore from Rio.

Brazilian exports consist mainly of manufactured products (including automobiles, machinery and footwear), minerals and foodstuffs as varied as coffee, beef and orange juice. But only thirteen percent of GDP comes from exports: Brazils growing domestic economy is the powerhouse of its development.

|

Carnaval

Carnaval plunges Brazil into the most serious partying in the world. Mardi Gras in New Orleans or Notting Hill in London are not even close; nothing approaches the sheer scale and spectacle of Carnaval in Rio, Salvador and Olinda, just outside Recife. But Carnaval also speaks to the streak of melancholy that is the other side of the stereotype of fun-loving Brazil.

Part of the reason is Carnaval's origins at the time when Brazil was still the largest slaveholding country in the Americas. The celebrations just before Lent acquired a kind of "world turned upside down" character, with slaveowners ceremonially serving their slaves food and allowing them time off work giving a particularly double-edged feel to Carnaval as servitude reasserted itself come Ash Wedneday. Brazil has come a long way since then, but the traditional freedom to transgress that comes with Carnaval gives its partying an edge that deepens in the small hours, as alcohol and crowds generate their usual tensions the already high murder rate hits its peak over the festival and traffic deaths are also at their annual high. There is a big difference between day and night. Carnaval during the