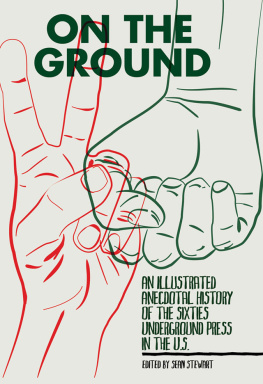

On the Ground

An Illustrated Anecdotal History of the Sixties Underground Press in the U.S.

edited by Sean Stewart

Copyright Sean Stewart, this edition copyright PM Press 2011.

ISBN: 978-1-60486-455-7

LCCN: 2011927951

Cover design by Simon Benjamin

Interior design by Josh MacPhee/Justseeds.org

Printed in the United States on recycled paper.

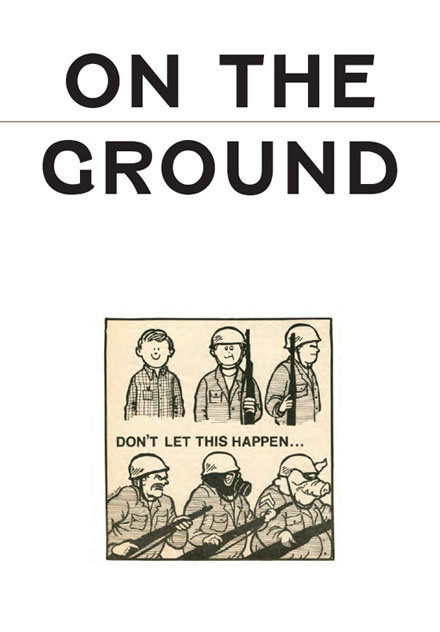

Image on page : Liberated Guardian, May 1, 1970.

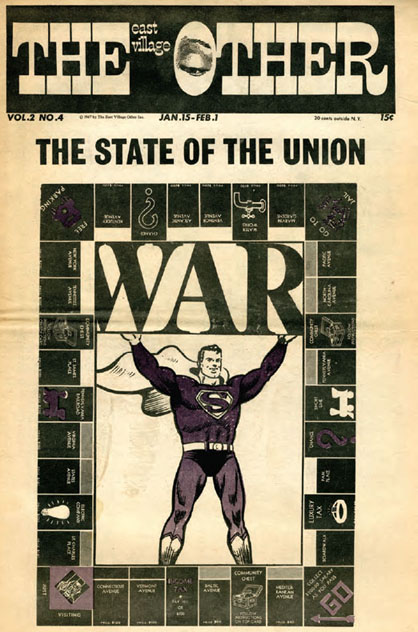

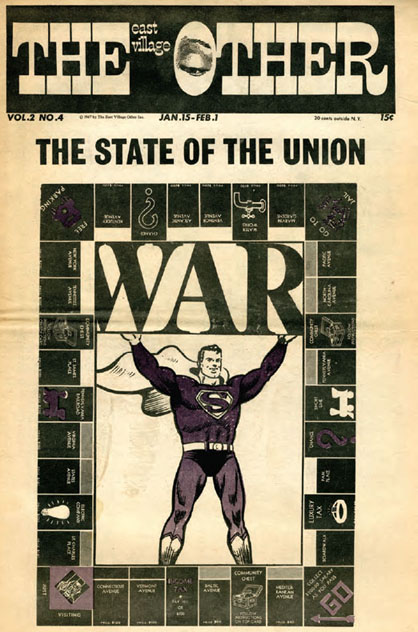

Image on page : East Village Other, vol. 2, no. 4 (1967).

Image on opposing page: Rising Up Angry, vol. 1, no. 10 (1970).

CONTENTS

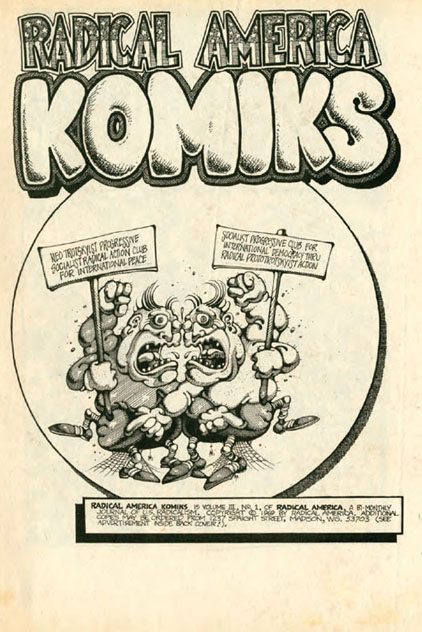

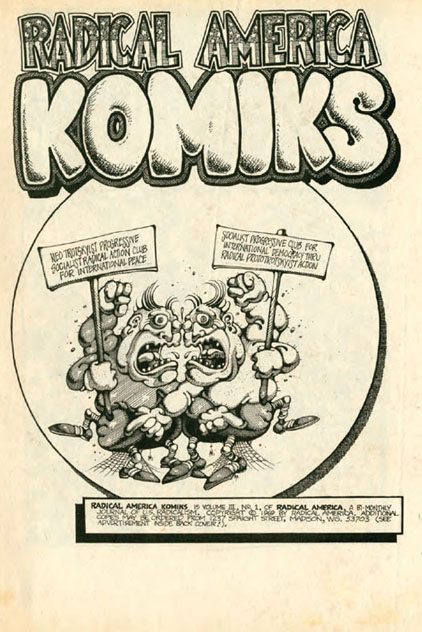

Radical America, vol. 3, no. 1 (1969). Title page artwork by Rick Griffin. Editor Paul Buhle enlisted Gilbert Shelton as guest editor for this popular all-comics issue of the SDS Magazine of American Radicalism.

PREFACE

Paul Buhle

T he underground press, lacking corporate support of any kind, largely local and grassroots even in its limited advertising base, yet flourishing for a half-decade in the United States, is nevertheless one of the great wonders of modern cultural politics. The creativity of local editors, artists, writers, and others (including this writer, mainly as a hawker of underground papers on a campus mall) did as much to advance the antiwar movement as any other force. In the process, theyor rather we, including naturally the millions of longhaired readers as wellchanged journalism, battled repressive laws, and had a mighty good time in the process. Looking back from forty years or so, it was the best time of our lives.

The title of this priceless collections first chapter, Like Mushrooms, recalls a populistic bumper-sticker slogan of uncertain political character from the eighties: They Must Think Im a Mushroom; They Keep Me in the Dark and Feed Me Bullshit. But perhaps the sensibility in this book better fits a popular slogan held aloft by activists in Wisconsin during the straggles of Spring 2011, against right-wing governors and legislators: S CREW U S AND W E M ULTIPLY!

The contributors and readers of the underground press may have been, as a group, the most comfortable generation materially in U.S. history, but we nevertheless felt screwed. The locked-down character of American culture, from the fifties, had not eased all that much even by the mid-sixties. Anything disliked could be called Communist and dismissed without a second thought, not only by segregationist rednecks in their own locales but by the New York Times reporters and editorial writers, whenever the subjects of a U.S. military occupation anywhere in the world did anything at all to try and end the occupation. The Beatles had appeared on the scene, following the rise and fall of early rock n roll, but popular culture was still dominated by the mostly idealized lives of the rich and powerful. Even the growing availability of the pill, altering the lives of young people, did not immediately change attitudes, especially public attitudes, toward sexual repression and the double standard.

Then something happened. Or to put it better, all hell broke loosebut (mostly, make that overwhelmingly) in a good way! Historians and memoirists are still trying to sort out the reasons, and they will not likely make a single, convincing case because no single case exists. For a little while there were overwhelming demographic contrasts between the readershipoften if by no means always long-haired, committed to the acceptability of social drug usage (if not personal use) and nonmarital sex but not the acceptability of warand the straights of Middle America, and in many places young versus not-so-young. So much of Americaincluding most of the South and rural districts, not to mention religious college campusesdid not read the underground press, that to generalize would be suspect. But millions did, simply because the underground papers suited their interests and perceived needs. For those who were potentially to be in Viet Nam, or had a brother, lover, or friend likely to be sent there, it was also a matter of life and death to get the news and insight somewhere.

The underground as a term may be found in many places across several centuries, but there can be little doubt that the most widely used identification, up to the middle of the twentieth century, identified anti-Fascist forces behind enemy lines of the Second World War, in much of Central and Eastern Europe, also large parts of Asia, where resistance movements largely led by Socialists and Communists engaged in illegal acts, at the cost of torture and murder if apprehended. The underground, not quite yet identified as such, had begun after Hitlers 1933 takeover in Germany and climaxed with the defeat of the Axis.

Popular culture, especially the Hollywood film of a certain type, celebrated the courage and self-sacrifice of the resisters. Humphrey Bogart famously gave up Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca for the sake of the antiFascist cause, but hundreds of resistance fighters in other films, hundreds of others in popular fiction, made worse sacrifices, while real-life members of the underground were slaughtered by the tens of thousands. Not long after the defeat of Germans and Japanese, the Cold War mood minimized the role of the underground, insisting that Allied troops had little assistance from behind the lines, and anyway the Resistance was tainted with Communist sympathies almost everywhere (an accurate charge). underground in that usage seemed to fade, and its companion resistance was applied to movements bent on overthrowing governments unfriendly to U.S. interests. (Suicide missions, a term of heroism in anti-Fascist and war films, popped up again decades later with the heroic suicide-missioners now mocked as fanatics: who else would consider such a thing?)

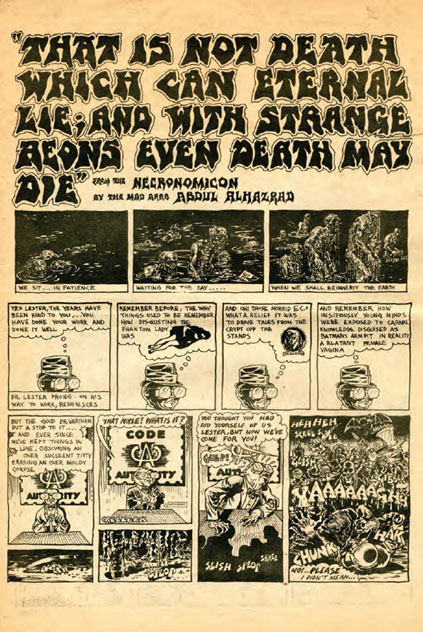

It was a bit surprising, then, to see nominally apolitical victims of the McCarthy Era, almost a decade later, to declare that they had gone underground against the censors of comic books. The occasion, a removal of comics not acceptable to the Comics Code (policed by an agency of the Catholic Church), sent the editors of MAD Comics into a high dudgeon of satirical art in 1955. A strip published shortly before MAD Comics became MAD Magazine (thus a black-and-white publication, no longer comics and not susceptible to censorship) showed an otherworldly figure who needed to be underground, effecting escaping the likes of Joe McCarthy and the FBI. Humor, real humor, had been forced underground.

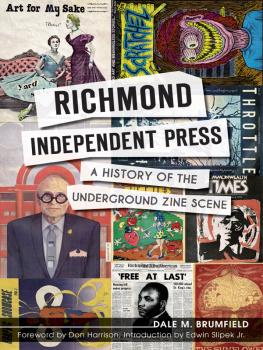

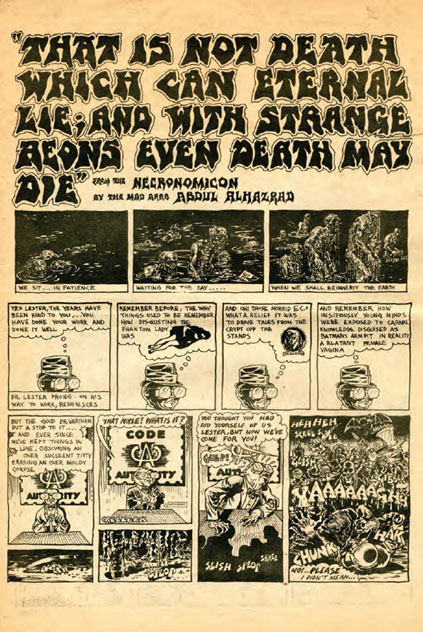

Gothic Blimp Works, no. 8 (1969). Up from under. Spain Rodriguez takes on the Comics Code.

Not everyone would have noticed this decidedly vernacular gesture. The editor and prime mover of

Next page