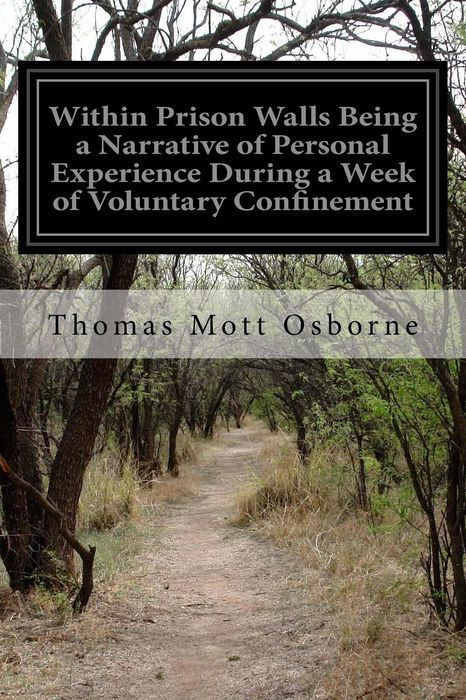

WITHIN

PRISON WALLS

BEING A NARRATIVE OF PERSONAL

EXPERIENCE DURING A WEEK OF

VOLUNTARY CONFINEMENT IN THE

STATE PRISON AT AUBURN, NEW YORK

BY

THOMAS MOTT OSBORNE

(THOMAS BROWN, AUBURN No. 33,333X)

NEW YORK AND LONDON

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

1928

Copyright, 1914, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

THIS LITTLE VOLUME IS DEDICATED TO

OUR BROTHERS IN GRAY

AND ESPECIALLY TO THOSE WHO, DURING

MY SHORT STAY AMONG THEM IN AUBURN

PRISON, WON MY LASTING GRATITUDE

AND AFFECTION BY THEIR COURTESY,

SYMPATHY, AND UNDERSTANDING

CHAPTER I

WHY I WENT TO PRISON

Many years back, in my early boyhood, I was taken through Auburn Prison. It has always been the main object of interest in our town, and I was a small sized unit in a party of sightseers. No incident of childhood made a more vivid impression upon me. The dark, scowling faces bent over their tasks; the hideous striped clothing, which carried with it an unexplainable sense of shame; the ugly close cropped heads and shaven faces; the horrible sinuous lines of outcast humanity crawling along in the dreadful lockstep; the whole thing aroused such terror in my imagination that I never recovered from the painful impression. All the nightmares and evil dreams of my childhood centered about the figure of an escaped convict. He chased me along dark streets, where I was unable to run fast or cry aloud; he peeked through windows at me as I lay in bed, even after the shades had been pinned close to escape his evil eye; as I ascended a flight of stairs in dreamland and looked back, he would come creeping through an open door, holding a long knife in his hand, while my mother all unconscious of danger sat reading under the shaded library lamp; he was a visitor frequent enough to make night hideous for a time, and it was many long years before he took a departure which I trust is final.

After this early experience I carefully avoided the Prison. Its gray stone walls frowned from across the street every time I departed or arrived on a New York Central train, but I made no effort to go again inside. In fact I persistently refused to join my friends whenever they made a visit there; once had been quite enough.

So it was not until many years afterward that I again passed within prison walls. Then my official connection with the Junior Republic and its successful training of wild and mischievous boys brought me in touch with the Prison System. I had been interested in the Elmira Reformatory and had visited Mr. Brockway, the superintendent of that institution. I became acquainted, quite by chance, with a certain prisoner in Sing Sing, and through him interested in other prisoners, there and in Auburn. In due time, I began to appreciate the importance of the general Prison Problem and the difficulties of its solution. Also I felt that my experience in the Junior Republic had given me a possible clew to that solution.

Thus I was drawn to the prison almost in spite of myself; and, becoming more and more interested, I felt that there was great need of some ones making a study at first handsome one sympathetic but not sentimentalof the thoughts and habits of the men whom the state holds in confinement. It is easy to read a textbook on civil government and then fancy we know exactly how the administration of a state is conducted; but the actual facts of practical politics are often miles asunder from the textbook theory. In the same way the Criminal has been extensively studied, and deductions as to his instincts, habits and character drawn from the measurements of his ears and nose; but I wanted to get acquainted with the man himself, the man behind the statistics.

So the idea of some day entering prison and actually living the life of a convict first occurred to me more than three years ago. Talking with a friend, after his release from prison, concerning his own experience and the need of changes in the System, I brought forward the idea that it was impossible for those of us on the outside to deal in full sympathy and understanding with the man within the walls until we had come in close personal contact with him, and had had something like a physical experience of similar conditions. We discussed how the thing could be done in case the circumstances ever came about so that it would become desirable for me to do it. He agreed as to the general proposition; but nevertheless shook his head somewhat doubtfully. There is no question but that youd learn a lot, he said; then added, but I think youd find it rather a tough experience. He made the suggestion that if ever the plan were carried out autumn would be the best season, as the cells would be least uncomfortable at that time of year.

Time passed, and while I continued to have an interest in the Prison Problem, the interest was a passive rather than an active one. Then on a red-letter day in the summer of 1912, being confined to the house by a slight illness, I read Donald Lowries book, My Life in Prison. That vivid picture of prison conditions, written so simply yet with such power and such complete and evident sincerity, stirred me to the depths. It made me feel that I had no right any longer to be silent or indifferent; I must do my share to remove the foulest blot upon our social system.

Thereafter when called upon to speak in public, I usually made Prison Reform the subject of my talk, advancing certain ideas gathered from my experience with the boys of the Junior Republic, endeavoring not only to crystalize my own views as to the prisons but to get others to turn their thoughts in the same direction.

Finally came an appointment by Governor Sulzer to a State Commission on Prison Reform, suggested to the Governor by Judge Riley, the new Superintendent of Prisons. My position as chairman of the Commission made it seem desirable, if not necessary, to inform myself to the utmost as to the inner conditions of the prisons and the needs of the inmates. I do not mean that it was necessary to reinvestigate the material aspect of the prisonsit is known already that the conditions at Sing Sing are barbaric, and those at Auburn medievalbut that it was desirable to get all possible light regarding the actual effect of the System as a whole, or specific parts of it, upon the prisoners.

I began to feel, therefore, that the time had come to carry out the plan which had been so long in the background of my mind. I discussed it long and earnestly with a certain dear friend, who gave me needed encouragement; the Superintendent of Prisons and the Warden at Auburn approved; and, last but not least, an intelligent convict in whom I confided thought it a decidedly good idea. None of us, to be sure, realized the way in which the thing was actually to work out. It became a much more vital and far-reaching experiment than we had any of us expected or could have dared to hope. We were not prepared for the way in which the imaginations of many people, both in and out of prison, were to be touched and stimulated.