THE EMBASSY

A STORY OF WAR AND DIPLOMACY

DANTE PARADISO

The views expressed in this book are the authors own and not necessarily those of the United States Department of State or the United States Government.

THE EMBASSY

Copyright 2016 by Dante Paradiso

FIRST EDITION

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Greene, Graham. Lawless Roads. 1960

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data On File

ISBN: 9780825308253

For inquiries about volume orders, please contact:

Beaufort Books

27 West 20th Street, Suite 1102

New York, NY 10011

Published in the United States by Beaufort Books

www.beaufortbooks.com

Distributed by Midpoint Trade Books

www.midpointtrade.com

Printed in the United States of America

Interior design by Mark Karis

Cover Design by Michael Short

Jacket Design by Mark Karis

Cover Images from Getty Images:

Top Image U.S. Air Force / Handout

Bottom Image Chris Hondros / Staff

For

ACCP

it must be difficult to shoot a laughing man:

you have to feel important to kill.

GRAHAM GREENE

In Memoriam

CHARLES SAYPAN

JAMES KORYON

SAMUEL KARTEE

CHRIS HONDROS

TIM HETHERINGTON

NABIL HAGE

JOSEPH ELLINGSON

ARTHUR A. DELA CRUZ

JOHN AUFFREY

AUTHORS NOTE

This book is a work of narrative non-fiction designed to place readers as much as possible alongside the actors in the incredible drama that occurred in Liberia in 2003. It has been written by stitching together the recollected experiences of those who were there based on interviews, conversations and other exchanges after the fact, as well as the authors own memories. The author was a political officer at U.S. Embassy Monrovia in 2003. A full list of persons interviewed is provided at the end of the text. The book also draws inspiration from the ample film, photographic and written record produced by the many news agencies and filmmakers who were in Liberia at that time. The text hews as closely as possible to the major facts and timelines of the war, but in reconstructing the thoughts, dialogue, and experiences of the actors, spoken language and descriptions have been shaped for clarity and narrative cohesion.

This book does not make use of cables or email traffic, or any other official, recorded nonpublic communications of the United States government. To the extent that such material may come to light and be at variance with what is presented here, it would be because memories or perceptions of events are different than whatever may have been recorded in official channels at the time. Of course, if any significant, material factual inaccuracies should be revealed, they should be brought to the attention of the author and/or the publisher so that appropriate corrections can be made in later editions.

PREFACE

LIBERIA SCENESETTER

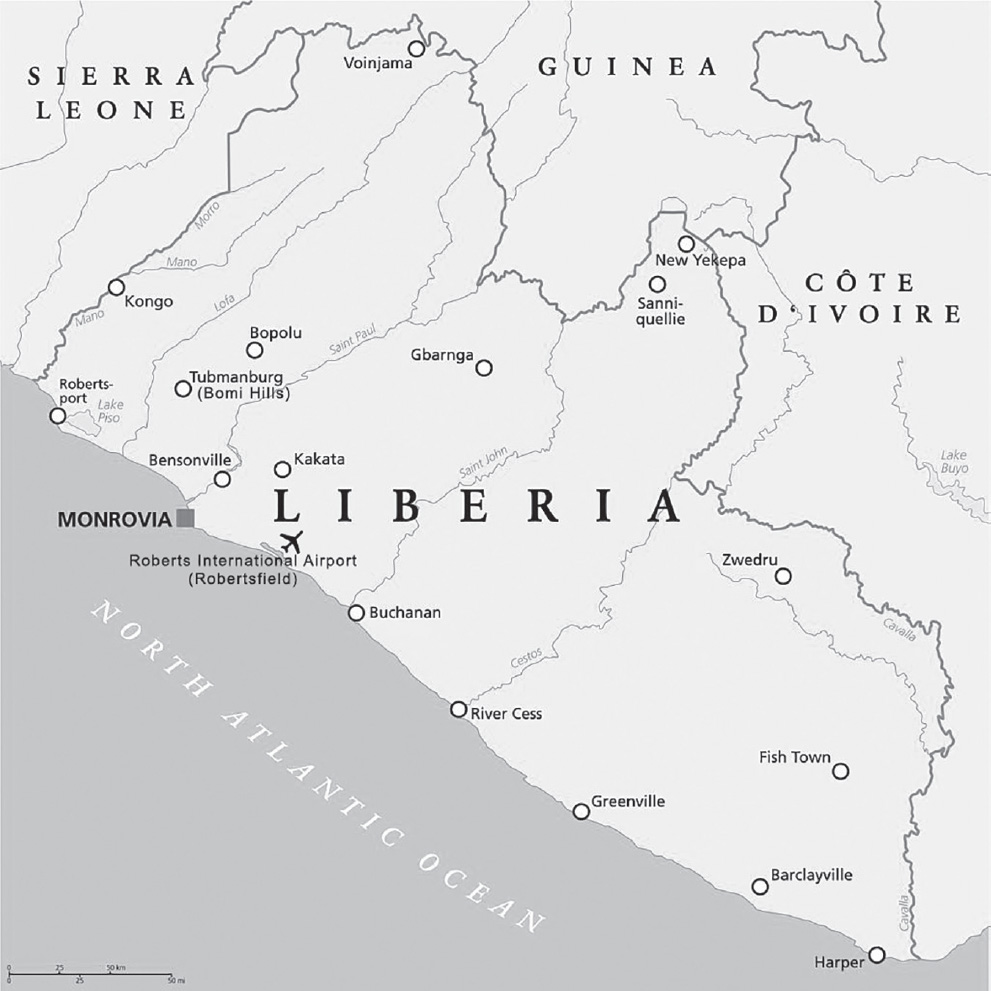

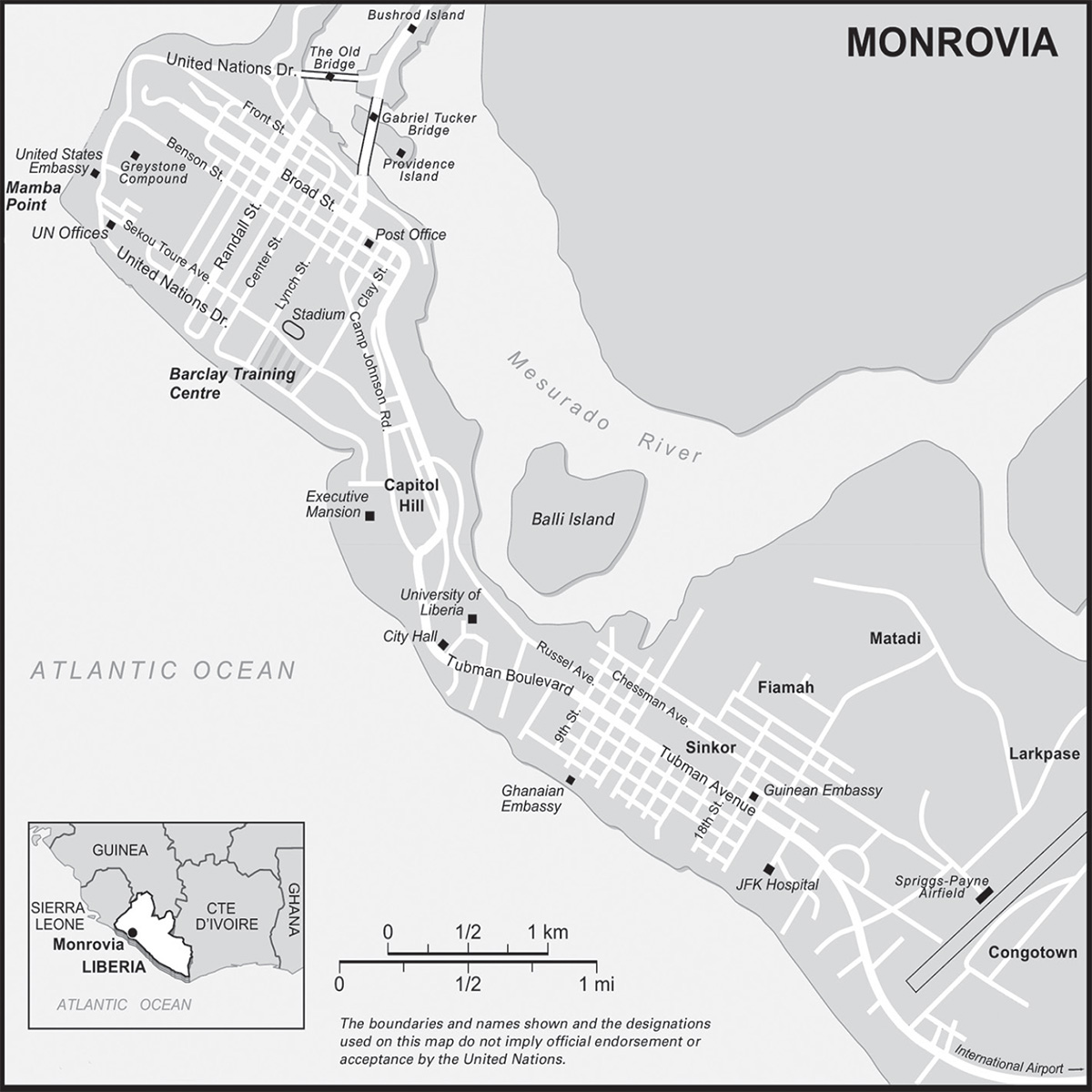

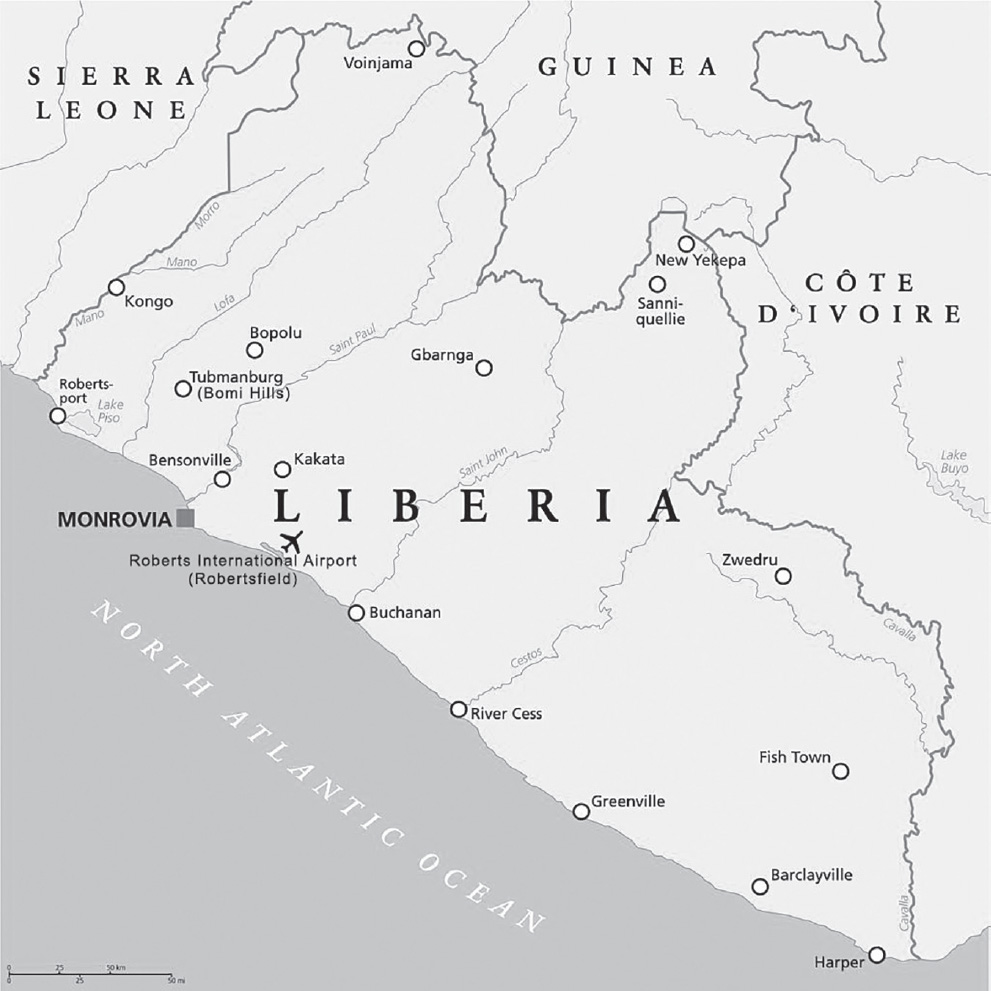

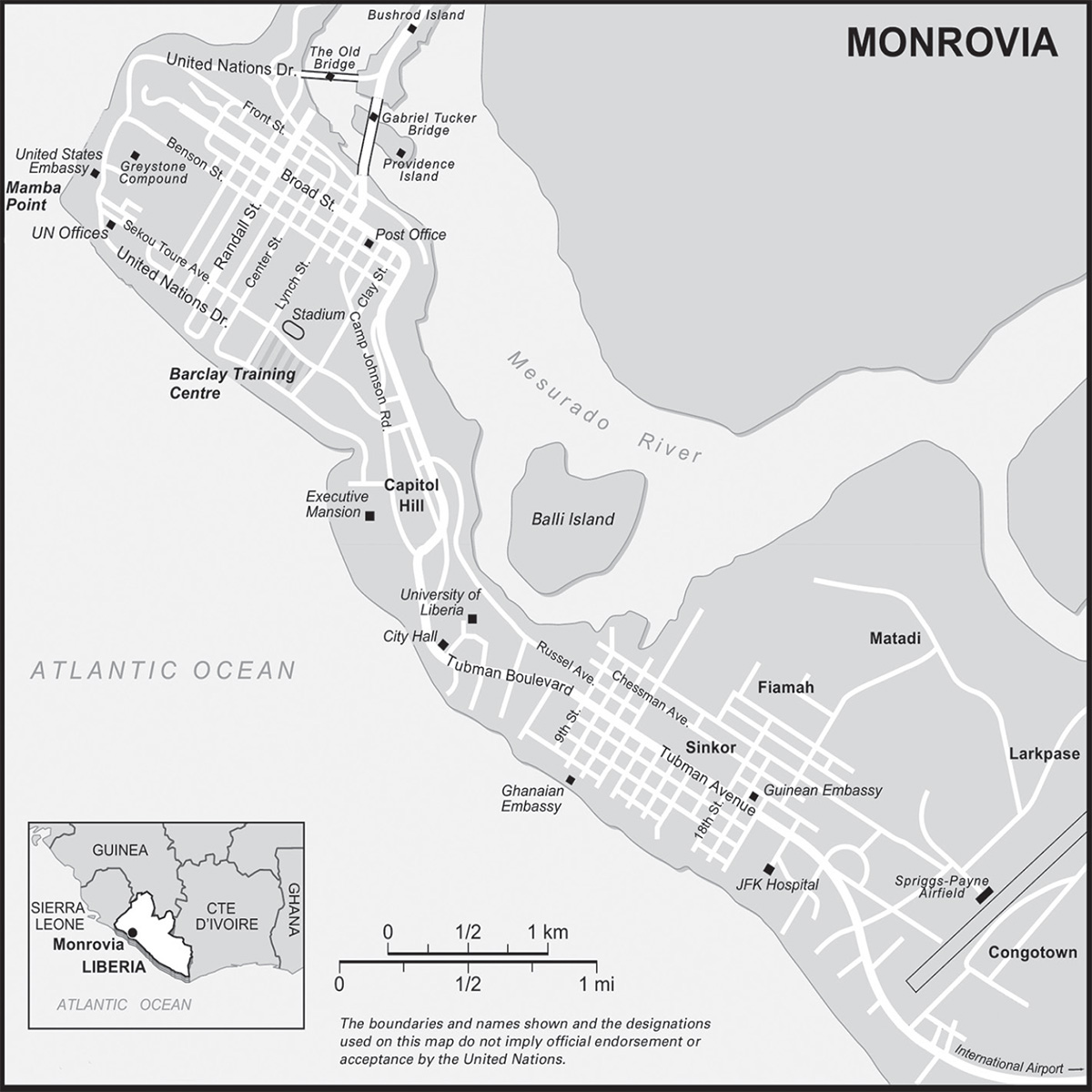

Liberia is an African country that started as an idea that did not come from Africa. In the 1820s, the United States Congress funded an American Colonization Society to return freed slaves to Africa, either as a philanthropic venture or as a facile attempt to resolve race problems by sending blacks back to Africa. The lands selected for the new state held much promise: rivers and coastal shoals teemed with fish; veins of gold and minerals ran through hills; and forests yielded teak, ebony, and other treasured hardwoods. Unfortunately, the riches also belonged to someone else, namely the sixteen tribes, give or take, who already lived there. This inconvenient fact did not deter the sponsors or the emancipated African-Americans, who sailed across the Atlantic in wooden galleys to West Africa and set up camp on a small island in the Mesurado River delta.

Over the next two decades the black colonists coaxed, cajoled, and clashed with the locals until they had their patch, and in 1847 these so-called Americo-Liberians established Liberia as Africas first independent republic in an area roughly the size of Tennessee. The Liberian constitution was drafted at Harvard, the Liberian flag patterned after Old Glory, and the Liberian capital named for U.S. President James Monroe, to honor his support for repatriation efforts. The Americos anointed themselves the governing class, though they were never more than a fraction of the countrys population and their numbers were bolstered only modestly over time through intermarriage with locals and by the embrace of various waves of Congo people, former slaves from European colonies and territories who had escaped or been liberated by the British navy. The new elites deeded themselves the best lands, wrote the laws favorable to their interests, and erected manses along the shore that, for many of the first settlers, recalled antebellum plantation houses they had left behind. They ruled Liberia from the comfortable shade of their verandahs and employed their African countrymen, the original tribes of Liberia, as cheap labor, sometimes as forced labor, while largely excluding them from politics and civic life. Liberia was even rebuked by the League of Nations for its labor practices, which in some cases were slave-like, and it took the government until the mid-nineteen thirties to codify some basic protections that ought to have been in place from the start for a country with its particular origins.

Although the United States established its first diplomatic mission in Africa in Monrovia, transatlantic communication in the nineteenth century was, as one might imagine, as slow as the sailing ships and steamers of the time, so for more than fifty years Liberia developed in relative isolation from the country that had birthed it. At the start of the new century, however, coincident with the rise of U.S. power, Liberian elites called upon their ties across the Atlantic to attract investment, which mostly took the form of concessional arrangements in rubber and mining. The most visible symbol of Liberias emergence as a U.S. trade partner was the Firestone Corporations sprawling rubber plantation, opened to support the rapid growth of the automotive industry.

With Liberian-American joint ventures as the core of its economy, Liberia over time came to be counted upon as a dependable U.S. ally and was called upon during World War II to support the fight against the Axis powers. U.S. engineers built Robertsfield, the national airport, as a refuel stop and depot for military planes headed to North Africa, and they later supervised the construction of the Free Port of Monrovia, financed through the Lend-Lease program, to ensure Liberias iron-ore could be brought to market. During the Cold War, the United States trained the Armed Forces of Liberia as a bulwark against the Reds and Liberia hosted a Voice of America complex, whose broadcasts from a network of towers north of the capital were intended to counter Soviet propaganda across much of Africa.

By the mid-1970s, the outsized U.S. diplomatic mission comprised multiple agencies, more than eight hundred officials, and family members. Monrovia became a most sought-after Foreign Service posting, known for pleasant beachfront housing, pools and lawn sports, somewhat reliable electricity and running water, and friendly locals who, for the most part, adored the United States. Liberian elites, in turn, embraced the relationship as never before. They traveled frequently back and forth to the United States and their children attended American colleges and professional schools. Family trees filled with dual-nationals and the notion of a special bond between the two countries, even if not fully reciprocated, was more or less taken as gospel. It was even built into school curricula. For Liberians of all stripes, the United States was forever patron and partner, known colloquially to those with means enough to visit as the Second Heaven and to everyone else as the Great United States or Liberias Big Brother Country. From time to time some even suggested, only half in jest, that the republic apply for statehood.