Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2021 by Raymond Guadagni

All rights reserved

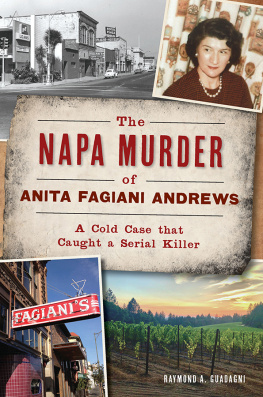

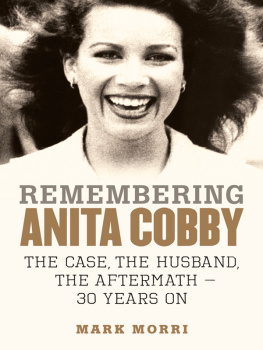

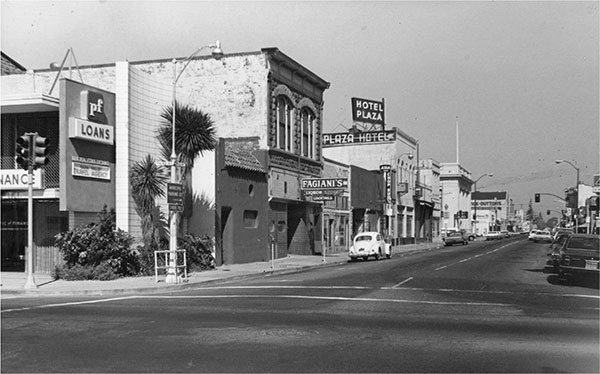

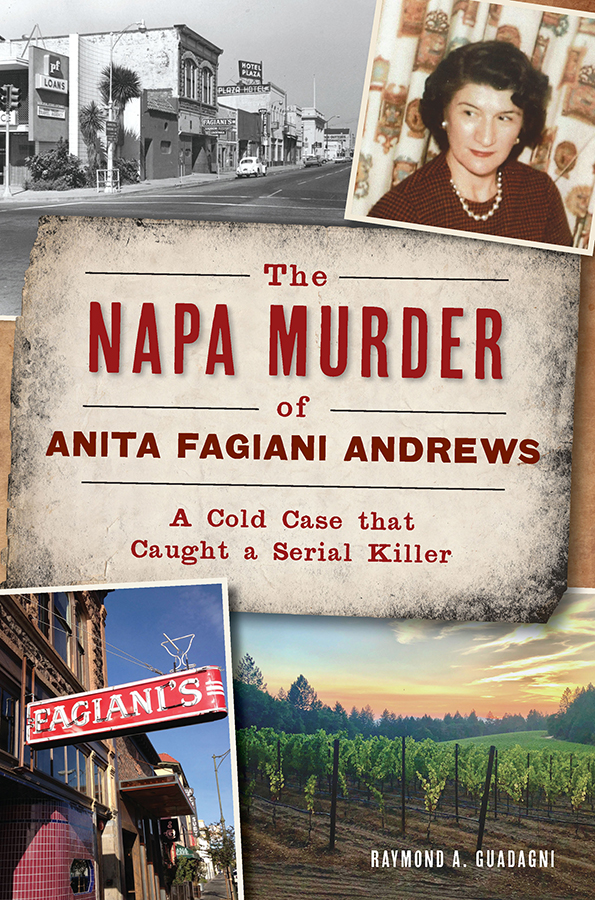

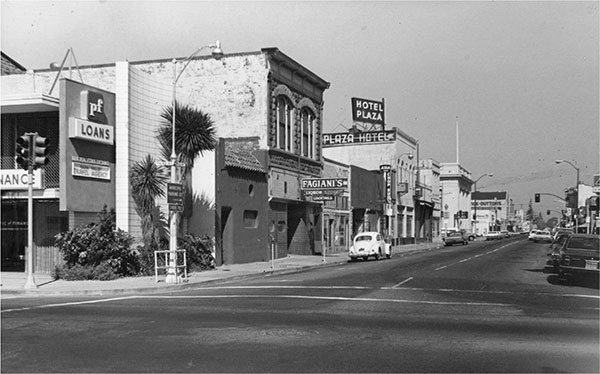

Front cover, clockwise from top left: View of Main and Third Streets, Napa, 1970s. Courtesy of the Napa County Historical Society; victim Anita Fagiani Andrews. Courtesy of the Napa County District Attorneys Office; Napa Valley vineyard. Photo by Raymond A. Guadagni; the iconic Fagianis sign, before it was removed for the major remodel by the new owner in approximately 2015. Photo by Raymond A. Guadagni.

First published 2021

e-book edition 2021

ISBN 978.1.43967.190.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020944243

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.741.5

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

DEDICATION

The events described in this book cover a period of thirty-seven years. Throughout that time, from 1974 to 2011, the work of the Napa Police Department officers exemplified their dedication, devotion and perseverance. Even though they were investigating a seemingly unsolvable case with no obvious suspect and no motive, they never gave up. These professional officers chased every lead, preserved every bit of evidence and spent countless hours working to solve the murder of Anita Andrews.

With the advancement in scientific techniques and the assignment of the case to Detective Don Winegar, and eventually the addition of District Attorney Paul Gero and Investigator Leslie Severe, the murder was finally solved, and the perpetrator was brought to trial.

This book is dedicated to those Napa police officers, and to capable police officers everywhere, for their hard work, for the emotional toll they pay and for how much they care about ensuring that justice is ultimately served.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I have received valuable help from many people in writing this book. First and foremost, I thank my wife, Ann, who provided assistance, suggestions and support and sacrificed both time and effort in this endeavor. She has always been my rock (and the rock for our entire family), and she graciously gave both her attention and her energy because she knew it was important to me. Without her, the book would not have been written.

Detective Don Winegar has been incredibly generous in furnishing me with his recollections, materials and timelines from the investigation as well as sharing countless communications during completion of this book. Dons contributions far outweigh any expression of gratitude I could offer him.

Thanks also to trial attorneys Paul Gero and Allison Wilensky, both of whom were tremendously cooperative, and to Investigator Leslie Severe, whose willingness to help went above and beyond. Leslie supplied many photographs and other materials used during the research on this book.

I am indebted to editor Carolyn Woolston, who is a superior wordsmith. Her suggestions were thoughtful and pertinent. On top of that, through this experience Ann and I made a new friend.

My sincere thanks to Todd Shulman of the Napa Police Department; to Kristen Wells at Stanford University, who supplied essential information about DNA testing; to court reporters Michelle Corrigan and Karen Kronquest for sorting through and supplying me with requested trial transcripts; and to friends who served as manuscript beta readers: Mary Butler, Laura Gorjance and Randy Snowden. I deeply appreciate your time and effort spent on my behalf.

I also want to thank the many people who willingly shared both their recollections of that fateful evening in 1974 and their memories of its effect on the small community of Napa at that time.

NAPA 1974

In 1974, Napa was a bucolic blue-collar town, where many locals worked in the agricultural industry. Almost everyone who lived in Napa worked in town, so there were few commuters other than to nearby Vallejo, a larger city about thirteen miles south that drew many Napans for work at Mare Island Naval Shipyard. Many of the nonagricultural workers were employed by Napa State Hospital or Kaiser Steel Fabrication Plant in Napa. There was very little tourism.

The population was predominantly Caucasian. African American, Asian and Hispanic residents represented a small portion of the total. Most migrant agricultural workers came for the grape harvest and then returned to Mexico or moved on to work the crops in other locales. There were very few good restaurants, and you had to travel out of town to see a play or hear a concert. Kids and teenagers complained there was nothing to do.

At the same time, the community was experiencing significant growth. Redevelopment was underway, and many older buildings were being razed and replaced with modern structures complemented by artwork, clock towers, attractive benches and brick walkways. Concerted efforts were being made to modernize the town and make it more attractive for downtown businesses. City Councilman James V. Jones remembered it this way: In many ways, things didnt seem much changed from the forties; when the sun went down, they rolled up the sidewalks.

Napa was considered a safe community. Many residents didnt lock their homes or their cars, and most people knew their neighbors. You couldnt walk anywhere in town without someone recognizing you and stopping to talk. Criminal activity was minimal, with few crimes other than alcohol-related offensesusually bar fights or driving under the influence of alcohol. There were very few armed robberies, murders, narcotics offenses, gang activity or reported sexual assaults.

Law enforcement described Napa as a whiskey- and beer-drinking town; there were twenty-one bars in the city and several just outside city limits. In 1972, twenty deaths in the county were caused by DUI drivers. Drunks were responsible for most of the assaults, stabbings and bar fights, as well. Napa police officer Ronald Hess recalled many a busy graveyard shift, often leaving the station at 11:00 p.m. with lights and siren, driving from bar fight to bar fight. In those days, the police didnt wear bulletproof vests, but they all wore blue-and-white riot helmets.

The intersection of Main and Third Streets marked the southwest corner of downtown Napa. The Conner Hotel stood on the east side of Main. Officer Hess succinctly described the Conner as a flophouse. On the ground floor of the Conner was the OK Corral bar, and across the street was Fagianis Cocktail Lounge, which the police regarded as a bar for old-timer drinkers. The Gilt Edge and the Oberon were located just up the block at Main and Second. One street over on Brown Street was the Plaza Hotel and Bar, which was a quieter lounge, though it, too, had its lively nights.

Next page