An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloging in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

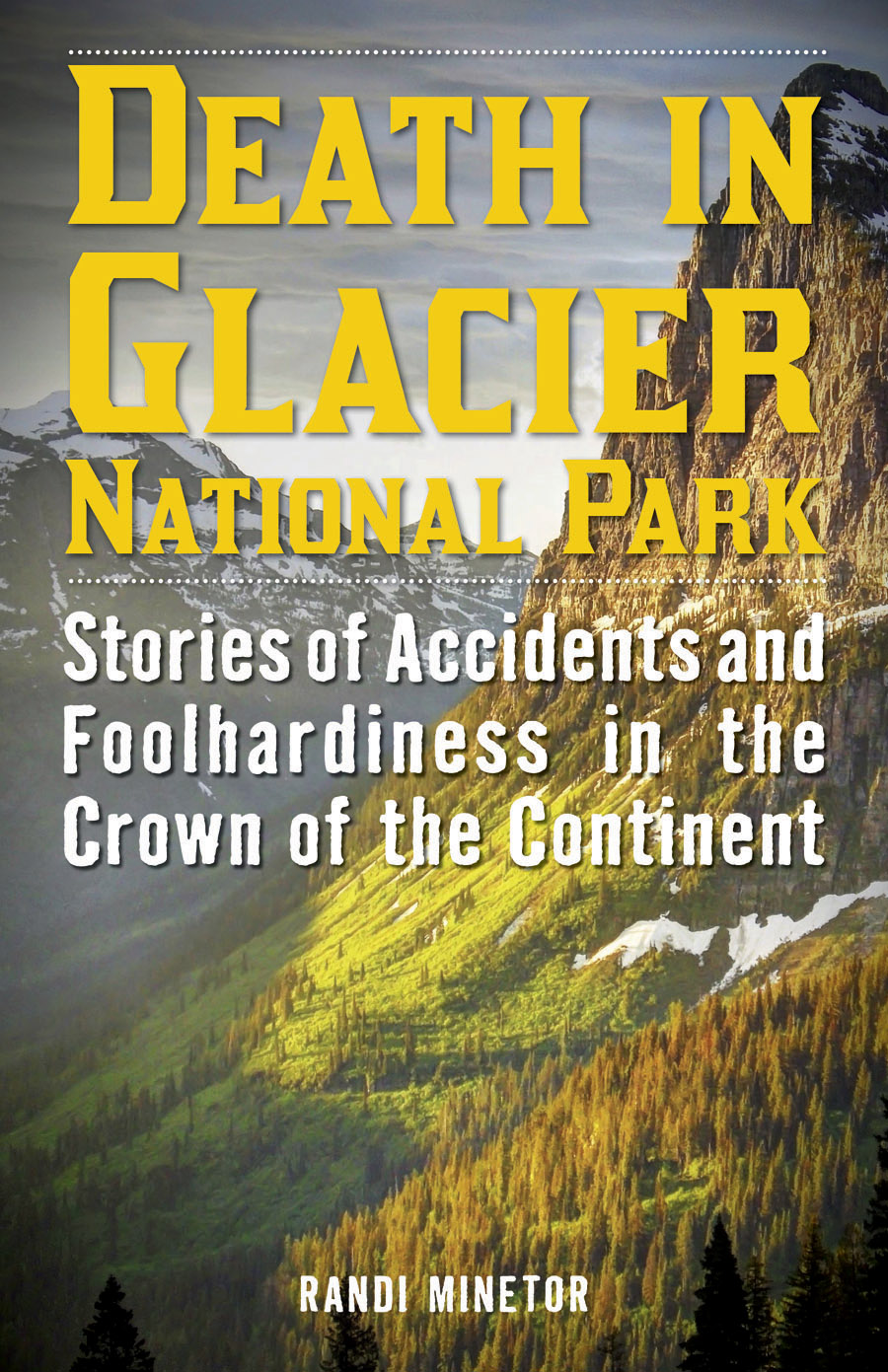

Names: Minetor, Randi, author.

Title: Death in Glacier National Park : stories of accidents and foolhardiness in the crown of the continent / Randi Minetor.

Description: Guilford, Connecticut : Lyons Press, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016001012 | ISBN 9781493024001 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781493025473 (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: AccidentsGlacier National Park (Mont.)Anecdotes. | Violent deathsGlacier National Park (Mont.)Anecdotes. | Bear attacksGlacier National Park (Mont.)Anecdotes. | Glacier National Park (Mont.)HistoryAnecdotes.

Classification: LCC F737.G5 M55 2016 | DDC 978.6/52dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016001012

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

PREFACE

THIS BOOK DETAILS MANY OF THE 264 DEATHS THAT HAVE taken place in Glacier National Park since the staff began keeping records in 1913, three years after Glacier became a unit of the National Park Service. I have endeavored to research every incident, but someparticularly those involving heart attacks or natural causeswere not covered by the media or chronicled in park documents. Other events (including a number of drowning accidents) must have been cataclysmic to the families involved, but they did not generate the media interest at the time to help me tell a detailed story today. In these cases you will find listed in this book's appendix the names, dates, and areas of the park in which the death occurred, but no other details in the chapters. If I appear to have skipped over your ancestor or loved one, I most likely could not find much information about his or her demise. Please feel free to get in touch with me at author@minetor.com to provide any factual information you may have, so I can include it in the next edition.

As you read this book, please keep in mind that an average of only 2.6 people per year lose their lives during a visit to Glacierand with 2,238,761 people visiting the park in 2014, this makes your odds of dying in the park about 861,062 to 1. Please do not take this concentration of stories as an indication that this spectacular park is a place to be feared. Instead, see them as the cautionary tales they are, further reinforcement of the basic rules of safety the National Park Service asks you to follow during your visit. (You'll find these rules and other survival tips in the Epilogue.)

Let me take this opportunity to encourage you, to urge you, even to insist that you plan a trip to northwestern Montana to enjoy Glacier National Park. Few places on the planet parallel its vast wilderness, the startling majesty of its high peaks, and its opportunities for views of charismatic megafauna, the large animals that people come from all over the world to see. This glacially carved landscape reminds us of the forces well beyond our own that first sculpted such magnificent places, and the responsibility we all have to preserve pristine environments like this one. I can't tell you how pleased you will be that you took the riskthe truly infinitesimal riskand made the trip to one of America's wildest places.

INTRODUCTION:

A GREAT VACATION GONE WRONG

THE STORIES YOU ARE ABOUT TO READ ARE ALL TRUE. SOME involve a little speculation about what may have transpired to cause the death in each case, but I have endeavored to be as factual as the media coverage and history allow.

There is no kinder way to describe what's in this book: These are stories about people going to a magnificent place expecting to have the time of their lives, and coming home dead. That being said, this book also brings to light the impressive facts of the massive search and rescue operations involved in attempting to save the lives of people who find themselves in trouble in Glacier National Park.

These are stories of daring rescues, uncommon teamwork, remarkable skill, and the many heroes throughout northwestern Montana who dedicate their professional and volunteer time to saving lives, or to recovering the bodies of people who have perished, so their loved ones can bring closure to their ordeal of loss. My research focused on those who died, but the park's records also are filled with stories of successful rescuestestaments to the training and courage of the rangers of the National Park Service, Flathead County Search and Rescue, North Valley Search and Rescue, Flathead Nordic Ski Patrol, Mountain Rescue Team, Two Bear Air, ALERT Air Ambulance at the Kalispell Regional Medical Center, the US Border Patrol, the US Forest Service, and the Flathead County Sheriff's Office. Together, this suite of rescue services handles more than five hundred calls every year, all but a handful of whose lives are saved. They are part of the reason that Glacier actually has one of the lower death rates in the National Park Service system, given the park's sizenearly one million acresand the number of visitors it draws (well over two million) on an annual basis.

Death in Glacier National Park is also the story of journalists, especially the ones who braved the risks of the wilderness to bring readers the most extensive coverage of these events. My hat is off to the writers at the Daily Inter Lake, the Independent Record, the Missoulian, and others whose excellent work gives us insights into the famous Night of the Grizzlies in 1967; the avalanches of 1953 and 1969; the disappearances and eventual discovery of pilot Donald Donovan and his passenger, Kathy See, and hikers Jake Rigby, Jakson Kreiser, and Yi-Jien Hwa; and the searches for Joseph and William Whitehead, F. H. Lumley, James Pinney, John Provine, and others whose remains may still linger somewhere in the park.

You will find all of these incidents treated with respect, even though some of them warrant a private guffaw at the misguidedness of people who venture off into the treacherous Glacier backcountry without carrying so much as a packet of trail mix, who ignore warning signs and guardrails as if the laws of physics do not apply to them, or who believe that climbing one of the park's highest mountains in the dead of winter ranks as an entry-level adventure.

Most of the people who have died in Glacier encountered sheer bad lucka stepping stone that looked stable and turned out to be slick, an icy crevasse hidden by new-fallen snow, or a boulder careening down from a rock face of its own volition. Others took precautions they considered adequate, without a true understanding of the danger present. It's one thing to stop and take photos of bears, for example, and quite another to fail to recognize that the advancing bear seen through your viewfinder is a wild animal about to attack. These people are not so much foolish as nave, lacking an understanding of nature as natural, and therefore distinctly different from the tightly controlled environment of an Orlando theme park.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.