Kathleen Snow has specialized in recent years in writing about our national parks. She is a member of the Montana Writers Guild. In 2016 Lyons Press published her nonfiction Taken by Bear in Yellowstone: More than a Century of Harrowing Encounters between Grizzlies and Humans.

Also in 2016 the University of Montana Press published her Searching for Bear Eyes: A Yellowstone Park Mystery. Her nonfiction has appeared in Harpers Magazine, Women in Natural Resources, and other periodicals.

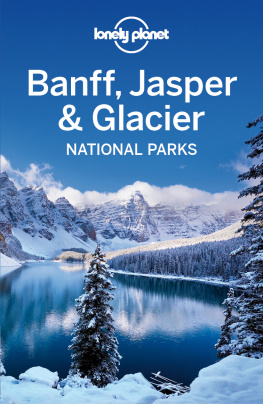

When spring comes again to Glacier National Park, the glaciers begin to melt. All beings strive for life, including people and bears. Every bear and every person has a story, which needs to be respected.

We have not forgotten Julie Helgeson and Michele Koons, who died that night in 1967. We honor their loved ones, family, and friends. We also have not forgotten Glacier Parks other known bear-caused fatalities: Mary Pat Mahoney, Jane Ammerman, Kim Eberly, Larry Gordon, Chuck Gibbs, Gary Goeden, John Petranyi, Craig Dahl, and Brad Treat.

We remember those who were injured but survived in the struggle of people and bears to coexist. We remember that bears are mortal too.

Montana Public Radio reported on November 21, 2018, that the year 2018 was the deadliest year on record for Montana bears since scientists started keeping track.... [There were] 51 [now 52] known and probable documented mortalities of grizzly bears in the NCDE [Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem], the huge swath of land in and around Glacier NationalPark. In addition to mortality due to age, injuries, and disease, grizzlies are euthanized for property damage, livestock predation, injuries to humans, and being habituated to humans. Grizzlies also die when hit by vehicles and trains, and in occasional accidents involving grizzly research projects and management operations such as relocation.

Each of us in the public can decide whether to do nothing, to do something to better safeguard people, and/or to preserve the grizzlies of Glacier Park. We can also educate ourselves on these issues, and practice, embody, and show others the Glacier Park guidelines for safer travel in bear country.

When thinking about preservation in general, consider this: If we take a step back from wherever we sit at this moment in time, we see the Blackfeet and the Kootenais at the edges of Glacier National Park, concludes the book, People Before the Park. But Glacier National Park, like the tribal homelands surrounding it, is also a remnant. At the same time, Glacier Park rangers are busier than ever. Rangers have experienced a 25 percent increase in calls for service to visitors in 2019, over 2018.

Statistics shared by Glacier National Park for one week in July show they responded to about 100 calls for service each day, the Missoulian reports on September 1, 2019, or 703 total in one week alone. Much of Glacier Park is out of cell-phone range, but If you call 9-1-1 in the Park, you will get a ranger, says Micah Alley, the ranger operations coordinator for the Park. Rangers retrieve locked keys in vehicles. They help change flat tires. Stranded at a trailhead? Theyll get you back to your vehicle. Theyll ticket you for leaving food or campsites unattended. Theyll adjudicate disputes over parking spots. Theyll race into the wild country to search for lost hikers. Theyll recover drowning victims, which is one of the leading causes of death in the park. Theyll arrest protagonists in domestic violence encounters. Theyll haze bears. Theyll carry people out of the backcountry on litters. Theyll go in search of human-habituated grizzlies.

People from all over the world come to Glacier National Park to experience and enjoy the wildlife and natural beauty. This affection may help to preserve Glacier Park long after the glaciers are gone.

Are grizzly bears a remnant?

I want to at least hope that when the clock ticks into the next millennium, writes Montana author Roland Cheek, that the childrens children of my children can still find an occasional grizzly bear in Glacier.

Can people and bears coexist?

In Glacier Park, as the arc of the year turns from spring to summer, fall to winter, the question remains.

One of the points of this book is the importance of that quintessentially human quality called altruism, even in the face of danger. To save a life, someone must find as quickly as possible any bear-attack victim who has been dragged away. The dragging away is itself predictive of predatory behavior, as opposed to a hiker surprising a sow bear who attacks to protect her cubs. In Julie Helgesons tragedy (, Finding Julie), four and a half hours elapsed from the time of the attack and finding her alive to when she was pronounced dead, despite the heroic efforts of three doctors and a nurse at Granite Park Chalet. To not go as quickly as possible to try to locate the victim is to sentence that person to the possible fate of being consumed alive.

I wish to thank former Glacier National Park superintendent Chas Cartwright, and current superintendent Jeff Mow, for their generous transparency in releasing the requested Case Incident Records of bearhuman encounters that constitute this book. I also thank their Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) officers, Amy Vanderbilt, Denise Germann, and Lauren Alley, and museum curator Jean Tabbert.

Each Glacier Park bearhuman encounter within this book has a Case Incident Record identified by number, which includes all relevant information gathered at that time.

For greatest accuracy, I chose to use these original National Park Service archives (and not depend on others later interpretations). Events of the time, related by those at that time in first-person narratives, are contained in this book. Any errors or omissions are my own.

Glacier National Park

Ashley, John. Photographs and essays by John Ashley. Glacier National Park After Dark: Sunset to Sunrise in a Beloved Montana Wilderness. Helena, MT: Sweetgrass Books, 2015.

Beaumont, Greg. Many-Storied Mountains: The Life of Glacier National Park. Washington, DC: Natural History Series, Division of Publications, National Park Service, 1978.

Brooks, Tad, and Sherry Jones. The Hikers Guide to Montanas Continental Divide Trail. Helena, MT, and Billings, MT: Falcon Press Publishing Co., 1990.

Byron, Eve. Calls for Service Keep Glacier Rangers Busy, Missoulian, Missoula, Montana, September 1, 2019.

Cheek, Roland. Chocolate Legs: Sweet Mother, Savage Killer? Columbia Falls, MT: Skyline Publishing, 2001.

Duckworth, Carolyn, ed. Hikers Guide to Glacier National Park. West Glacier, MT: Glacier Natural History Association, 1978, 1996.

Guthrie, C. W., and Dan and Ann Fagre. Death and Survival in Glacier National Park: True Tales of Tragedy, Courage and Misadventure. Helena, MT: Farcountry Press, 2017.

Hanna, Warren L. The Grizzlies of Glacier. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 1978.

Holterman, Jack. Place Names of Glacier National Park, 3rd ed. Helena, MT: Riverbend Publishing, 2006.

Kimball, Shannon Fitzpatrick, and Peter Lesica. Wildflowers of Glacier National Park and Surrounding Areas. Kalispell, MT: Trillium Press, 2005.

Leftridge, Alan. Glacier Day Hikes, 3rd ed. (now with GPS-compatible maps). Helena, MT: Farcountry Press, 2003.

Lomax, Becky. Glacier National Park Moon Handbook, 5th ed., New York: Carroll & Graf / Avalon Travel Publishing, 2009.

Martinka, C. J. Paper 13, Ecological Role and Management of Grizzly Bears in Glacier National Park, Montana. Published at the Third International Conference on BearsTheir Biology and Management, June, 1974. Binghamton, New York, USA, and Moscow, USSR. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Morges, Switzerland, 1976.