J ust about every baseball fan knows the basic outlines of Hank Aarons story.

J ust about every baseball fan knows the basic outlines of Hank Aarons story.

Poor kid from segregated Alabama comes of age not long after Jackie Robinson breaks baseballs color line. He is already a certain Hall of Famer when it suddenly becomes clear that he, not one of his more celebrated contemporaries like Willie Mays or Mickey Mantle, is the guy who has the best chance to eclipse Babe Ruths career home-run record. Fifty years ago, 714 was nearly 200 homers ahead of anyone in the games history. It was unassailable. Unreachable. But year after year, sweet swing after sweet swing, Aaron drew closer.

Not in 50-, 60-, or (absurdly and inauthentically) 70-homer chunks, but by hitting between 40 and 47 homers (never more than that) eight times and 39 twice more. A model of enduring excellence. A marvel of consistency and dedication to craft. Just as a baseball story, this would be compelling enough. But of course, there was more. On April 8, 1974, as Hank Aaron stepped to the plate against the Dodgers Al Downing, in a ballpark in the Deep South, he had already endured years of racist taunts, hate mail, and death threats.

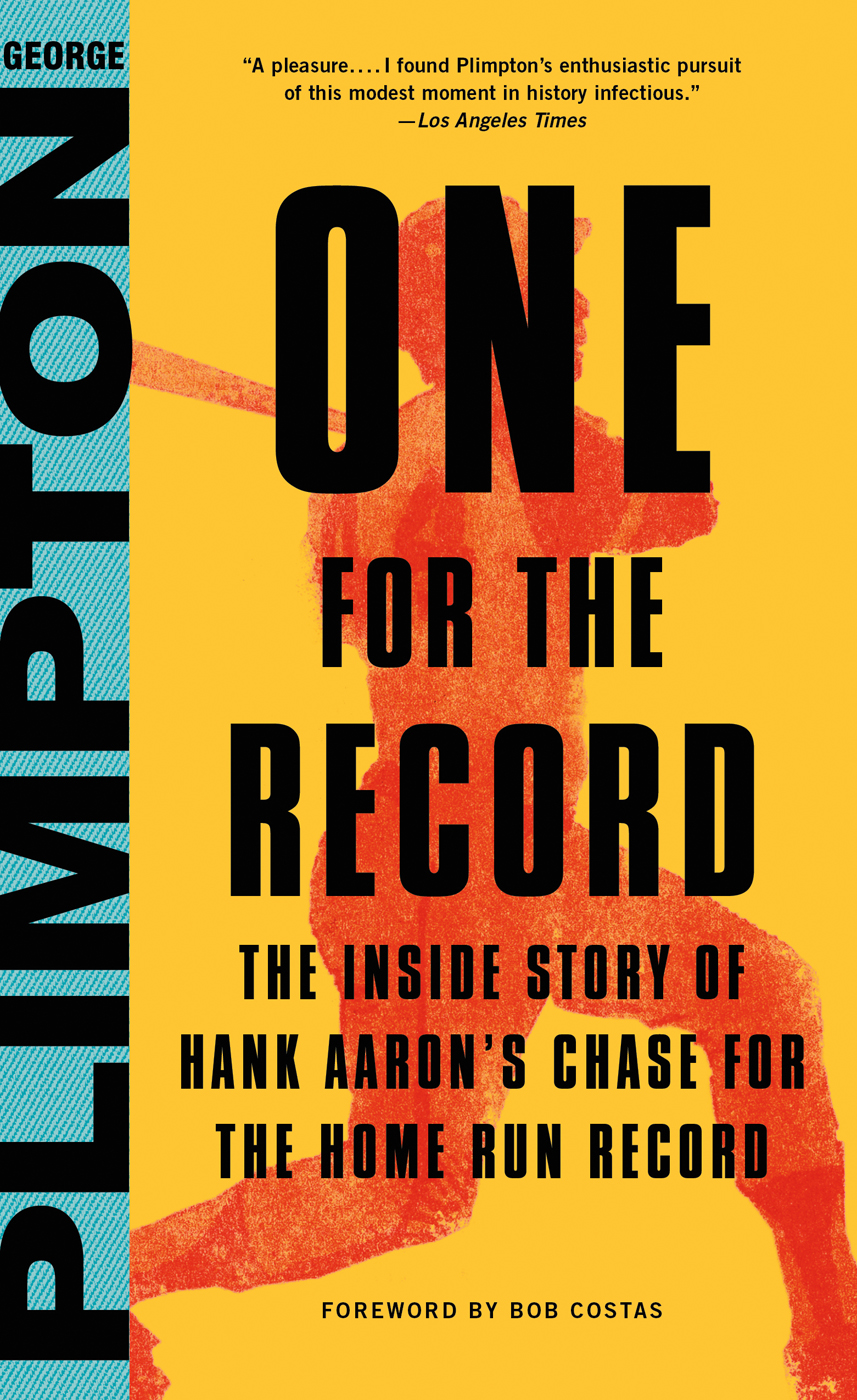

Some portion of America was still uneasy with black athletes in general. But a black man passing the Babe? A black man owning baseballs most cherished record? That was more than some could abide. Or rationalize. Hank Aaron withstood all that, his dignity and sense of purpose undiminished, remembered now as someone who stood for something even more than his brilliance as a ballplayer. Those are the broad strokes of Hank Aarons story. But to appreciate and capture the full texture of his life, and especially the rich details of the years and moments leading up to and surrounding that record-setting night, well, thats where George Plimpton comes in.

As graceful a writer as Aaron was an outfielder, Plimpton brought to the task genuine empathy, curiosity, a keen eye for detail, and, when it came to great athletes, his odd and endearing combination of sophistication and childlike awe. It was only natural he would be drawn to Aarons story and do it justice. I have known Hank Aaron for many years and consider him a friend. He is among the most significant and admirable people I have met in sports. I was also lucky enough to have crossed paths with Plimpton on several occasions. We were friendly acquaintances.

He was always good company, in person and on the page. It is a pleasure to be in his company again, rereading and appreciating anew both the writer and his subject. It was a simple act by an unassuming man which touched an enormous circle of people, indeed an entire country. It provided an instant which people would remember for decadesexactly what they were doing at the time of the home run that beat Babe Ruths great record of 714 home runs which had stood for 39 years, whether they were watching it on a television set, or heard it over the car radio while driving along the turnpike at night, or whether a neighbor leaned over a picket fence and told them about it the next morning.Its effect was far-reaching, and more powerful than one would expect from the act of hitting a ball over a fence. The sports correspondent from El Sol de Mxico, almost overcome with emotion, ended his piece on the Aaron 715th home run with thanks to God. We lived through his historic moment, the most fabulous in the world.

Thanks to God we witnessed this moment of history.In Japan the huge headlines in Tokyos premier sports daily read haiku-like: WHITE BALL DANCES THROUGH ATLANTAS WHITE MIST and under the subhead I SAW IT the correspondent began: In my Atlanta hotel room I now begin writing this copy. I know I have to be calm. But I find it impossible to prevent my writing hand from continuing to shake.It caused tragedy. In Jacksonville, Florida, a taxicab driver shot himself when his wife pulled him out of his chair in front of the television to send him out to work just as he was settling down to the game. He died before the home run was hit.In what might have seemed an illogical place, the instant caught the commissioner of baseball, Bowie Kuhn, addressing a Cleveland Indians Booster dinner in the Cleveland Stadium Club. In the controversy which had boiled up over Aarons wish to skip the Cincinnati series and open in Atlanta before his hometown fans, the commissioner had ruled against him and ordered him to play.

Kuhn had vowed to be on hand for 715, but the moment found him on the dais reminiscing about Johnny Allen, the Indians pitcher famed for disconcerting batters with a tattered sleeve on his pitching arm.Almost everyone else in baseball was in front of a television set. In Kansas City the ancient black pitcher Satchel Paige had 17 of his family crowded around (all these sisters-in-law of mine) and when they saw the ball hit they began shouting and they could hear the people next door carrying on the same way.

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.