SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bocca, Geoffrey. The Life and Death of Sir Harry Oakes. New York: Doubleday, 1959.

Donaldson, Frances. Edward VIII. Philadelphia and New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1974.

Higham, Charles. The Duchess of Windsor. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1988.

Houts, Marshall. King's X. New York: William Morrow, 1972.

Leasor, James. Who Killed Sir Harry Oakes? Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983.

"The Murder of Sir Harry Oakes," The Nassau Daily Tribune, 1959.

Pye, Michael. The King Ch'er the Water. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1981.

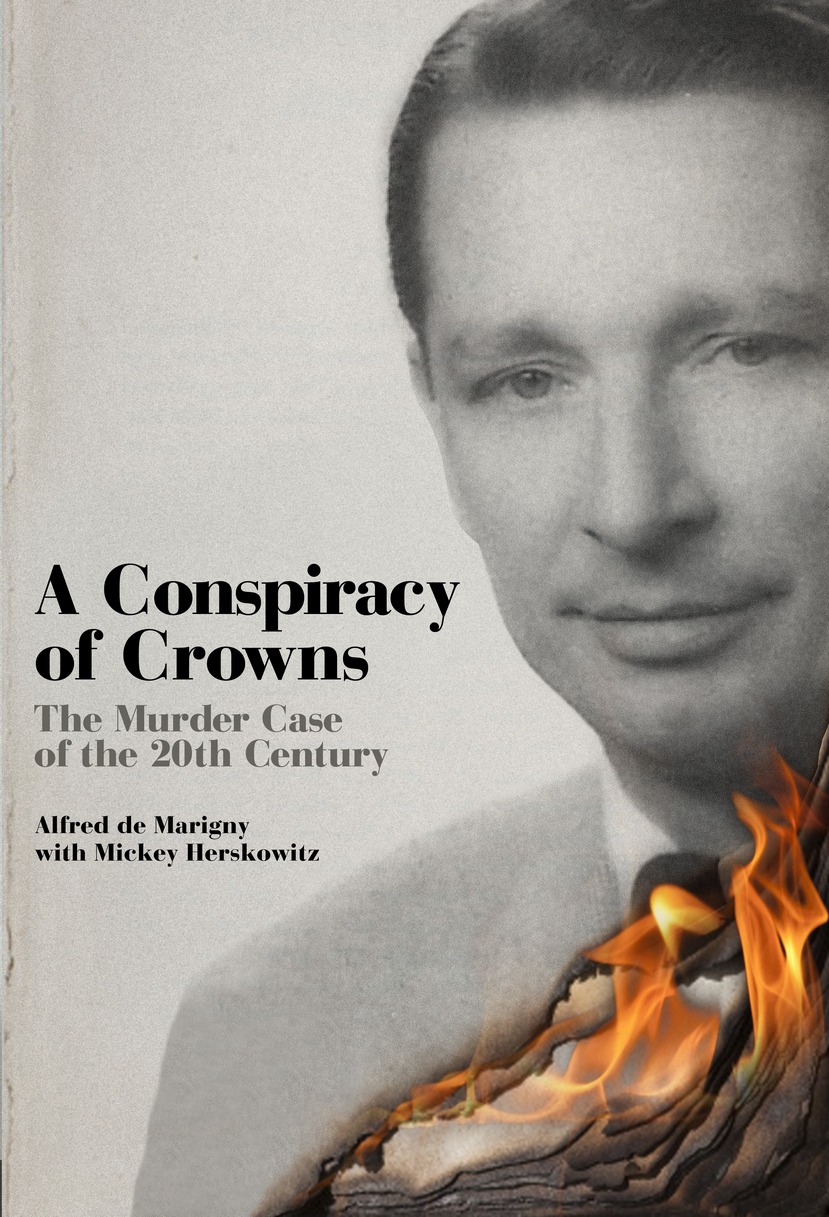

A CONSPIRACY OF CROWNS

Photograph credits appear with the captions. Those not credited are from the personal collection of Alfred de Marigny.

ISBN: 978-1-939430-18-2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Garrett County Press Digital For more information, please address

www.gcpress.com

To Curtis Thompson,

known as George,

and to Montreal's Jewish community of the mid-forties,

led by Moses Miller, Philip Joseph, and Harry Rajinsky.

In the darkest hours of my life, they

defined for me the word friend.

Acknowledgments

I made a promise to certain loved ones not to refer to them, or thank them, by name. But they know who they are and what they have meant to my life and this book.

In expressing my gratitude elsewhere, there are no such restrictions. Scott Williams, a young and brilliant friend, was always supportive and helpful in interpreting legal details. It also helps to have an attorney in the family; my daughter-in-law, Sidney de Marigny, was helpful in obtaining documents that had been previously classified.

In organizing literally thousands of pages of transcript and early drafts, my coauthor was assisted by Patrick Bishop, whose insights were welcome.

In the tedious process that involves keeping the computer running and the printer printing and the pages in the right order, thanks are due to Sid Clinton and Ida Levinson.

I was challenged by, and enjoyed comparing notes with, the writer Charles Higham, whose book The Duchess of Windsor included a provocative chapter on the Oakes case. Another author who fell under the thrall of this story was Geoffrey Bocca, who encouraged me, up to the time of his death from cancer, to tell my side of it.

As a patient and understanding editor, the best kind, Betty Prashker guided us with gentle hands. Her associate, Lisa Healy, gave us the friendly and essential closing push.

I approached the task of writing this book with the most tangled of feelings. Now it is done. I am more convinced than ever that no one will resolve the contradictions of the case, either the murder of Sir Harry Oakes or the attempt to frame me for it. The description of my trial is based on the transcript of the testimony as kept by the Chief Justice, who wrote it by hand, with a quill pen. Although not all of his notes are legible, the accounts of the testimony vary little in the newspapers of the day and the books that appeared later.

What I can add to the dryness of the daily record is truly my ownmy thoughts, my knowledge of the characters, how I appraised the evidence and the people who gave it. On the subject of how Oakes died, and why, I differ emphatically with most of what has been written. But to all who have kept alive an interest in this case, and the injustice that grew out of it, I give my thanks.

Predestination brought everyone in this book to play a part in my life. Each one had a definite place at a definite time, similar to the units of a jigsaw puzzle. Every piece was part of a whole.

PART ONE Fool's Gold: The Cast,

the Scene, the Crime

1. WIND, RAIN, AND FIRE

There is a cycle in life in which friends become enemies, and winners become losers, and the cycle goes the other way as well. This is true among men as it is among countries, and it is part of a story that began on a summer's night in Nassau, the Bahamas, and continues nearly half a century later. The islands were not yet the tourist attraction they would in time become, but even as the globe was engulfed in war, Nassau fulfilled its role as a sanctuary for the rich, the spoiled, and the shadowy.

Between midnight and dawn on the morning of July 8, 1943, one of the richest men in the British Empire was murdered in his bed, in a sprawling home at the water's edge. He was Sir Harry Oakes, sixty-eight, an eccentric and complicated man who roamed the earth before discovering a legendary gold mine.

Doctors would find four wounds to the head, each the size of a fingertip, behind the curve of the left ear. The bed had been set afire, scorching the body in no discernible pattern, and reducing to rags the front of his pajamas. Only tatters of mosquito netting still dangled from the ceiling.

Blisters were visible on Sir Harry's neck, chest, and groin, and on the left knee and foot. His face was blackened by smoke and soot, and feathers from a torn pillow were pasted to the raw skin, stirring slightly, like moths, in the air of an electric fan facing the bed a few feet away.

He had been found lying on his back in bed, but, oddly, a line of blood seemed to flow in the wrong direction, upward, from the left ear, over his cheek, and across the bridge of the nose. Either the law of gravity had been defied, or his killer had left him facedown, his head hanging toward the floor.

A trail of charred carpet led across the bedroom, into the hallway, and down the staircase, and yet no flames had reached the ceiling, and the bedroom walls were almost undamaged. When the first doctor reached the scene, the mattress still smoldered in one small spot beneath the body. The doctor doused it with water from a drinking glass.

Muddy tracks ran through the house. A typical Nassau storm had blown up during the evening, squalls with winds fierce enough to bend the tall palms as if they were made of rubber.

A million tourists have come and gone in the years since the morning of that gruesome discovery. Reporters, authors, amateur detectives, even a few pros have poked around the islands, searching for the missing clue that would solve the crime. Still the same questions are heard:

Who killed Harry Oakes? Why? And how?

For reasons that are still a matter of conjecture, no specific instrument of death was ever established. Theories about the murder weapon would spread like crabgrass. From that moment on, half a dozen lives would be rearranged, and a mystery would surface that endures to this day.

That week, the Allied forces had invaded Sicily, and Mussolini's Fascist government was on the verge of collapse. Tens of thousands were dying across Europe, Asia, and Africa. But the murder of Harry Oakes landed on page one of newspapers around the globe. Who would have dared to invent such a melodramatic crime: a stormy night, an exotic island, a grizzled old gold prospector, all at the doorstep of a former King of England?

The Bahamas had just begun to emerge as a playground of the idle rich. But this act seemed a throwback to other eras, to a long history of what might be called institutional violence: piracy, shipwrecking, bootlegging.

No stranger to the rougher edges of life, Oakes boasted of the enemies he made. He might have been killed out of fear or greed or hate.

Oakes was crude and ill-tempered, his nature made tough by early hardship and suspicious by late wealth. He was, from all accounts, a man of modest sexual experience when he married at forty-eight. His wife, Eunice, was half his age. He had traveled around the world in search of the riches he never doubted he would find, and had worked his claims in places that are now a part of folklore: Yukon Territory, the Klondike, the Belgian Congo, Death Valley.