Contents

Guide

THE STORY OF YOUR DOG . Copyright 2022 by Brandon McMillan. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

FIRST EDITION

Cover design: Faceout Studio

Photography: Kremer/Johnson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

Digital Edition APRIL 2022 ISBN: 978-0-06-304067-0

Version 02242022

Print ISBN: 978-0-06-304064-9

To my late brother Brian.

I miss you every day.

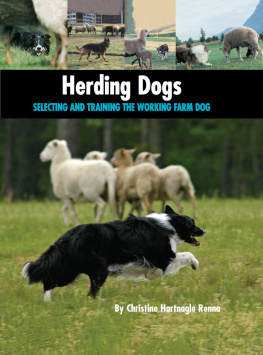

I was a teenager the first time I saw a rookie border collie at a herding ranch. This dog was six months old and had never seen sheep in her life. She was completely untrained and naive to the worldbut the minute she caught sight of the flock, her body stiffened, her head dropped, her ears flattened, and her entire frame leaned with attention as she went into full stalking mode. Zeroed in on the animals, she burst into action, charging at the flock, running circles around them, and nipping at their heels. In under a minute, fifteen meandering sheep became a tight, compact group, ready to be safely penned up for the night.

My jaw dropped. I asked the ranch owner how the pup could possibly know what to do without any training. She looked at me and then at the dognow looking every inch a puppy again, with one ear up, one ear down, and her whole body twitching with excitement as she watched over her sheep. The owner shrugged and said simply, They were wolves.

Of course that was only half the story. Wolves arent known for their sheepherding. The rest happened in the thousands of years that passed between ancient wolves and that modern-day border colliean evolutionary process that may be unequaled by any other creature. The wolf became domesticated by and bonded to humans, then underwent a long, slow, definitive transformation from all-purpose omnivore to the perfect dog for herding sheep.

What I witnessed that day shifted my entire perspective on dogs, and over the years, I became a more accomplished animal trainer because of it. I realized that the primal drives each animal carries within are critical components in our human understanding of dog behavior and what compels those behaviors in the first place.

On a hypothetical level, we all know dogs are descended from wolves. Of course they are. But few of us take that fact into account when we look at our own dogs. More often than not, we imagine them kind of like furry childrenprojecting simplified versions of our own logic and emotions onto them. When they bolt out of the yard, we think theyre being naughty, rather than following their instincts to seek prey. When they get snippy around the food bowl, we call it aggression, rather than a defense tactic. When they maniacally race around the house or go crazy on a toy, we say theyre being playful, rather than striving to fulfill their genetic impulse to exhaust each days mountain of energy. When they pee on the floor after an hour alone, we think theyre spiteful, rather than the truththey are so stressed at being separated from their pack they can hardly stand it.

And this is just the beginning of the miscommunications and misunderstandings between humans and dogs. The critical fact we tend to forget is that fifteen thousand years of genetics factor into every move our dogs make. Every issue, personality trait, and quirky habit of our domestic dogs is rooted in links to their ancestors and the ensuing centuries of domestication and job-specific breeding.

History shaped domestic dogs and then their breeds, coaxing their behavior away from wildness, shyness, and the other survival, territorial, and mating instincts of wolves. Humans set out to make wolves cooperative, and eventually worked to recast them as specialized dogs, experts at valued jobs like guarding, herding, and hunting. It worked. Over time, we created hundreds of different breeds capable of doing highly specific, useful jobs for us.

Fast-forward to the twenty-first century, when less than 5 percent of dogs have ever even had an obedience class. Only a minuscule portion of them work, doing jobs they were designed to do. Many of those tasks are obsolete now anyway. Instead, todays pet dogs are lounging on the couch, snoozing in the bed, chasing their tails in the backyard, bounding after tennis balls, or romping in the dog park. Theyre bringing laughter and companionship and love to our lives. At least the lucky ones are. The not so fortunatedogs I see all the time as part of my workare huddled in cages at animal shelters, not knowing their lives are at stake or why. Far too often the reasons go right back to their wolf origins and their job-specific breeding. Dogs are abandoned because theyre too energetic or too aloof, too aggressive or too defensive, or even because they get too lonely, whiny, and dependent.

To say the fate of both naughty dogs and shelter dogs who end up in trouble is not their fault is an epic understatement. Humans spent thousands of years selecting and shaping these creatures to behave a certain way. Now that we dont needor even likesome of those traits anymore, theres no easy way to turn them off.

Case in point: several years ago, I took my Jack Russell terrier out for a quiet morning at a dog-friendly park. I picked a sunny spot, spread a blanket, stretched out, and opened a book. My dog Pepe (more about him in ) took off to engage in his favorite sport: squirrel chasing. He had caught plenty of rats, but squirrels were his pipe dreamthe ones that always got away. Everything was right with the world until I caught sight of an idyllic scene unfolding about thirty yards away. A little girl, five or six years old, was slowly, gently reaching her little hand toward a fat squirrel to offer him a peanut. She set it on the ground beside her foot, and the squirrel calculated the risk and stepped in to grab it. He scurried a few feet up a tree trunk and proceeded to eat the peanut while the kid watched and laughed. Her parents looked on, smiling. Heck, it was so sweet I smiled, toountil I caught a glimpse of Pepe, maybe twenty feet from this family, his attention fixated on that squirrel.

It happened fast. The girl offered another peanut, the squirrel edged her way, Pepe saw his chance, and he took off like a shot. As the child, her family, and a few other folks who had been enjoying the peaceful morning looked on, Pepe sank his teeth into the poor distracted rodent, then gave it a giant shake that surely broke its neck and killed it instantly. The girl screamed, the father shouted, the mom went running toward Pepe, but he was not quite done. As we all looked on in horror, he braced the squirrels body with his right front paw, decapitated it in one swift motion, trotted over to me with the head in his mouth, and dropped it at my feet.

All eyes turned to me then, father of the monster.

Trust me when I tell you there is no etiquette that works in that momentno suitable gesture or polite words that can make it right. Logic and history told me my dog had acted on an instinct as primal and deep as the urge to eat or to mate, something honed in his breed until it was sharp and undeniable, but that was not the moment to explain such a thing to a crying child or a bunch of disgusted onlookers. Instead, I scooped up dog, book, and blanket, and started what felt like a miles-long walk of shame to the car. For his part, Pepe had at last caught his white whale, and he held his head high.