John Hersey - Of Men and War

Here you can read online John Hersey - Of Men and War full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Pickle Partners Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Of Men and War

- Author:

- Publisher:Pickle Partners Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Of Men and War: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Of Men and War" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

In five true stories of World War II

- The Battle of the River

- Nine Men on a Four-Man Raft

- Bories Last Battle

- Front Seats at Sea War

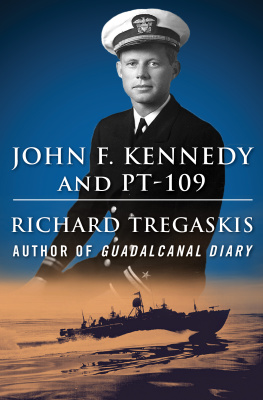

a famous war correspondent takes you aboard John F. Kennedys doomed PT-109...into the horror of Guadalcanal...onto a death raft in the Southwest Pacific.

Of Men and War — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Of Men and War" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1963 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

OF MEN AND WAR

BY

JOHN HERSEY

Contents

John Hersey was born in Tientsin, China, in 1914 and lived there until 1924, when his family returned to the United States. He attended Hotchkiss School, was graduated from Yale in 1936, and then went to England to study at Clare College, Cambridge, for one year. Upon his return to this country, he was private secretary to Sinclair Lewis for a summer. Hersey has been a writer, editor, and war correspondent for Time and Life, a writer for The New Yorker and other magazines. Since 1947 he has been devoting most of his time to fiction.

The stories in this book describe some of the sensations of what has come to be called conventional warfare. This refers to all those forms of war that do not involve the use of atomic weapons.

In another book, Hiroshima , I have given an account of what happens to those on whom atomic warfare is waged. Nearly everyone agrees that the most urgent strivings of the worlds statesmen must be toward the goal of prohibiting atomic warfare foreverfor in it, if it occurs, there will be no victory for anyone, only general disaster for all mankind.

There are some who feel that conventional wars not only will be fought in future but even can be justified. I am not one of them. The stories in this volume may help readers to see why warfare, conventional or otherwise, cannot be justified as a means of settling disputes between nations, for these are stories of what common men, not necessarily leaders or heroes, feel as they wage warand their feelings are inevitably reduced, in the end, to what men cannot help feeling about their worst crime, which is murder.

The terrain, the weapons, and the races of war vary, but certainly never the sensations, except in degree, for they are as universal as those of love.

On the surface the sensations of war, as these stories reveal them, may not all seem to be sensations of suffering, pain, discomfort, and guilt. Some seem to be wildly pleasant sensations. I will point to only one example: the strange, giddy elation of the men on the bridge of the U.S.S. Borie when they have their adversary, a German submarine, pinned beneath their ship in a kind of death grip. But I would suggest that this is a glee of briefest duration, for it combines two guilty elements: relief at the thought that the other human being, not the self, is to die; and, far worse, an upsurging drive to destroy. This drive is present to some degree in all of us, but living in a world at peace most of us succeed in diverting it into acceptable and harmless outlets. One of the worst things about war is that it renders this destructive urge respectable and even, it appears, praiseworthy. Men have been known to get medals for displaying it.

It is true that warfare does also provide men with occasions for selfless generosity toward their fellows, of a sort that we call heroic sacrifice. The concern of young Lieutenant John F. Kennedy for his wrecked crewmen, in the now-famous episode of the survival of the youth destined to be President of the United States, and the gentle but costly care of Jim Hosegood for his delirious friend, in the story of the aviators crowded on a too-small rubber raft at seathese are examples of human love at work under harrowing circumstances. But occasional sacrifice does not justify widespread pain; a hundred heroes do not restore one life unjustly lost.

War does ask courage of men, but so does peace. Indeed, I hope that this bookshowing instances of courage and cowardice, of heroism and utter selfishness, of love of life and disgusting bloodlustwill help readers to make a leap of imagination, to arrive at this fact of our time: peace is a far sterner challenge than war. War is the easy way out, the primitive resort to rage and killing. Peace, whether national or personalthe solution of problems without recourse to fighting, yet without compromising principlesrequires of us greater stamina, greater sacrifice, greater forbearance, greater endurance, greater patience, greater resourcefulness, greater love, and even greater physical courage, by far, than giving vent to violence.

This is the story of a crucial episode in the life of John F. Kennedy, who, seventeen years after these events, became President of the United States.

The time of these occurrences was August, 1943 . I wrote the account a few months later, when Kennedy had been returned to the United States for recuperation and for separation, in due course, from the service . He told me the story one afternoon when I visited him in the New England Baptist Hospital, in Boston, where the disc between his fifth lumbar vertebra and his sacrum, ruptured in his crash in the Solomons, had been operated upon; and I asked if I might write it down. He asked me if I wouldnt talk first with some of his crew, so I went to the Motor Torpedo Boat Training Centre at Melville, Rhode Island, and there, under the curving iron of a Quonset Hut, three enlisted men named Johnston, McMahon, and McGuire filled in the gaps.

IT SEEMS that Kennedys PT, the 109, was out one night with a squadron patrolling Blackett Strait, in mid-Solomons. Blackett Strait is a patch of water bounded on the northeast by the volcano called Kolombangara, on the west by the island of Vella Lavella, on the south by the island of Gizo and a string of coral-fringed islets, and on the east by the bulk of New Georgia. The boats were working about forty miles away from their base on the island of Rendova, on the south side of New Georgia. They had entered Blackett Strait, as was their habit, through Ferguson Passage, between the coral islets and New Georgia.

The night was a starless black and Japanese destroyers were around. It was about two-thirty. The 109, with three officers and ten enlisted men aboard, was leading three boats on a sweep for a target. An officer named George Ross was up on the bow, magnifying the void with binoculars. Kennedy was at the wheel and he saw Ross turn and point into the darkness. The man in the forward machine-gun turret shouted, Ship at two oclock! Kennedy saw a shape and spun the wheel to turn for an attack, but the 109 answered sluggishly. She was running slowly on only one of her three engines, so as to make a minimum wake and avoid detection from the air. The shape became a Japanese destroyer, cutting through the night at forty knots and heading straight for the 109. The thirteen men on the PT hardly had time to brace themselves. Those who saw the Japanese ship coming were paralyzed by fear in a curious way: they could move their hands but not their feet. Kennedy whirled the wheel to the left, but again the 109 did not respond. Ross went through the gallant but futile motions of slamming a shell into the breach of the 37-millimetre anti-tank gun which had been temporarily mounted that very day, wheels and all, on the foredeck. The urge to bolt and dive over the side was terribly strong, but still no one was able to move; all hands froze to their battle stations. Then the Japanese crashed into the 109 and cut her right in two. The sharp enemy forefoot struck the PT on the starboard side about fifteen feet from the bow and crunched diagonally across with a racking noise. The PTs wooden hull hardly even delayed the destroyer. Kennedy was thrown hard to the left in the cockpit, and he thought, This is how it feels to be killed. In a moment he found himself on his back on the deck, looking up at the destroyer as it passed through his boat. There was another loud noise and a huge flash of yellow-red light, and the destroyer glowed. Its peculiar, raked inverted-Y stack stood out in the brilliant light and, later, in Kennedys memory.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Of Men and War»

Look at similar books to Of Men and War. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Of Men and War and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.