Other books by Sylvain Tesson

Consolations of the Forest

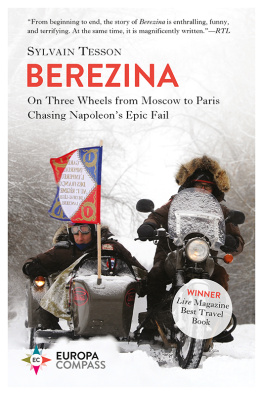

Berezina

PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2019 by ditions Gallimard

Translation copyright 2021 by Frank Wynne

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Originally published in French as La Panthre des neiges by ditions Gallimard

Copyright Vincent Munier for the photograph reproduced on

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Tesson, Sylvain, 1972 author. | Wynne, Frank, translator.

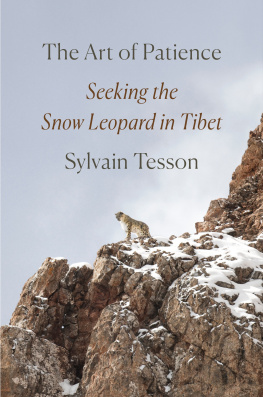

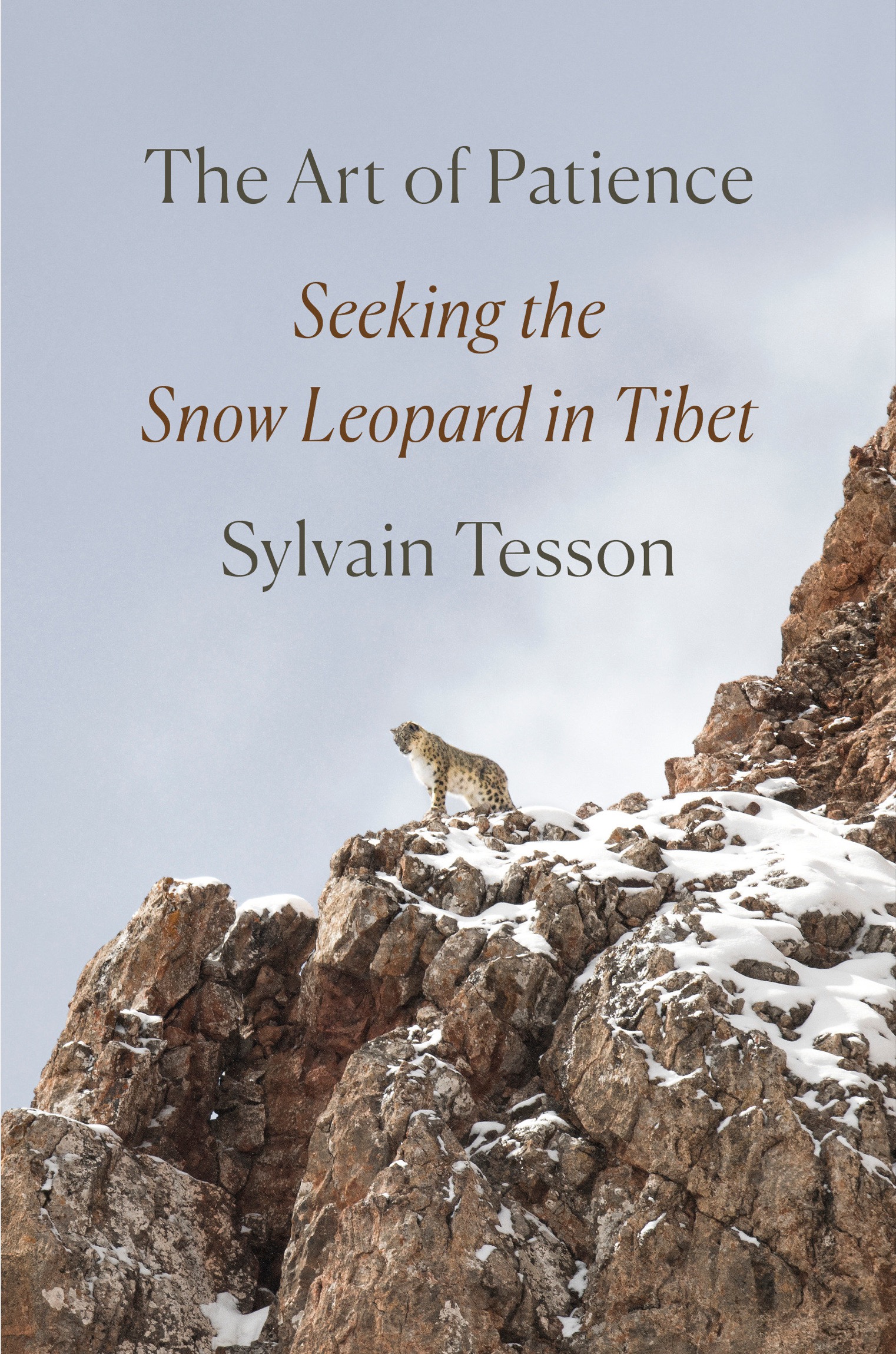

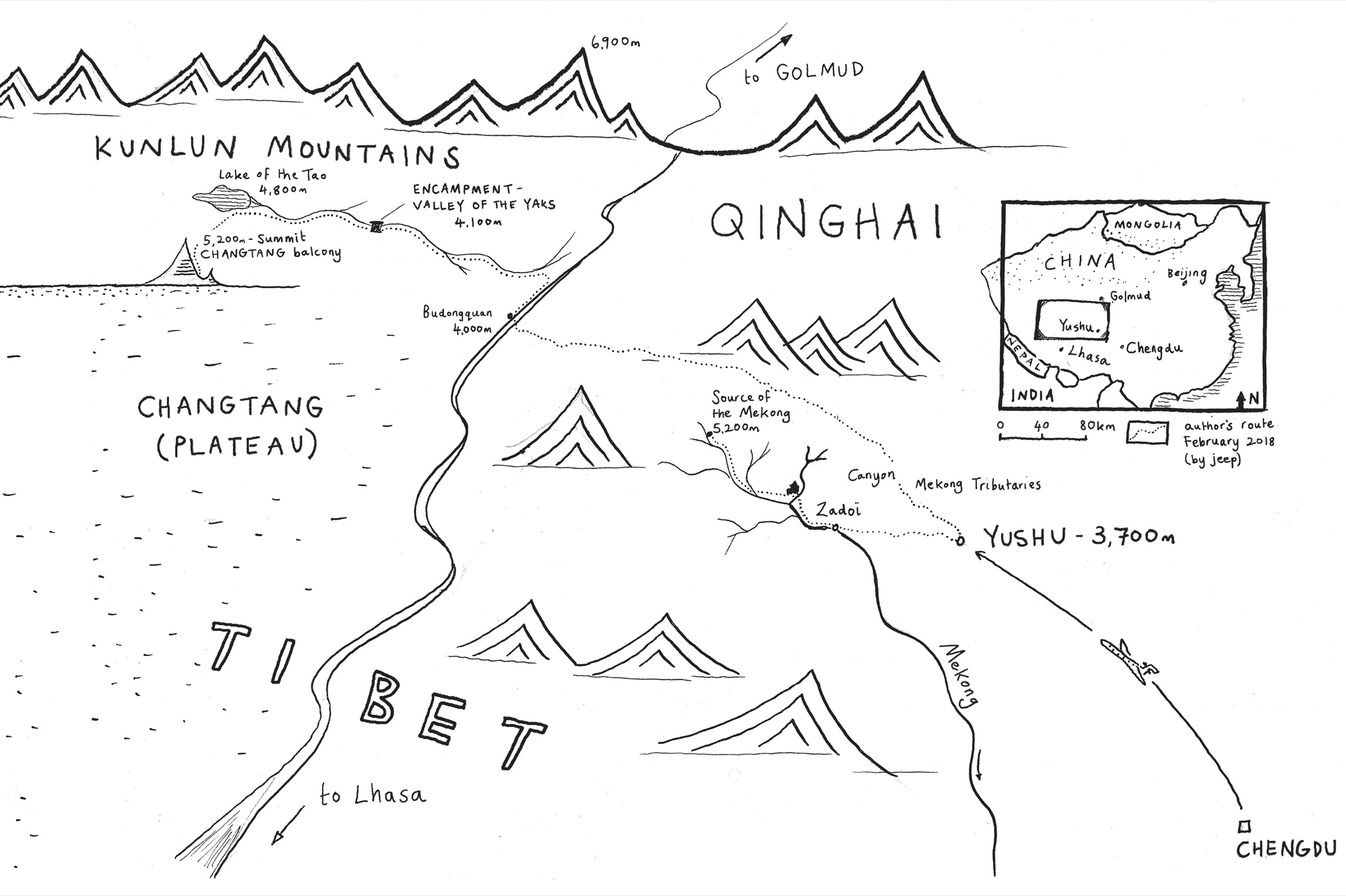

Title: The art of patience: seeking the snow leopard in Tibet / Sylvain Tesson; translated from the French by Frank Wynne.

Other titles: Panthre des neiges. English

Description: New York: Penguin Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020052516 (print) | LCCN 2020052517 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593296288 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593296295 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Tibet Autonomous Region (China)Description and travel. | Tesson, Sylvain, 1972 TravelTibet Autonomous Region (China) | Snow leopardTibet Autonomous Region (China)

Classification: LCC DS786 .T45413 2021 (print) | LCC DS786 (ebook) | DDC 915.1/504612dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020052516

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020052517

Cover design: Stephanie Ross

Cover photograph: Vincent Munier

Designed by Cassandra Garruzzo, adapted for ebook by Cora Wigen

pid_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

To the mother of a lion cub

The females of all animals are less violent in their passions than the males, except the female bear and the leopard, for the female of these appears more courageous than the male.

Aristotle

The History of Animals, IX

Contents

Preface

I had met him one Easter day, at a screening of his film about the Abyssinian wolf. He had spoken to me about the elusiveness of animals and of the supreme virtue: patience. He had told me about his life as a wildlife photographer, and explained the technique of lying in wait. It was a delicate and rarefied art that involved hiding in the wild and waiting for an animal that could not be guaranteed to appear. There was a strong chance of coming away empty-handed. This acceptance of uncertainty seemed to me to be very nobleand by the same token anti-modern.

Could I, who loved to run like the wind over lowlands and highlands, manage to spend hours, silent and utterly still?

Lying among the nettles, I obeyed Muniers precepts: not a movement, not a sound. I could breathe; this was the only vulgar reflex permitted. In cities, I had grown accustomed to prattling about anything and everything. The most difficult thing was saying nothing. Cigars were prohibited. Well smoke later, down by the river, Munier had said, it will be night and fog! The prospect of lighting a Havana on the banks of the Moselle made it easier to endure the position of prostrate watcher.

Life was exploding. The birds in the trees streaked the night sky, they did not shatter the magic of the place, did not disturb the order of things, they belonged to this world. This was beauty. A hundred meters away, the river flowed. Swarms of dragonflies hovered over the surface, predatory. On the western bank, a hobby falcon was diving. Its flight was hieratic, precise, deadlya Stuka.

This was not the time to allow myself to be distracted: two adult badgers were emerging from the sett.

Until it grew dark, all was a mixture of grace, of drollery, of authority. Would the badgers give a signal? Four heads appeared, and the shadows darted from the tunnels. The twilight games had begun. We were posted ten meters away, and the animals were oblivious to our presence. The badger cubs tussled, scrabbled up the embankment, rolled into the ditch, nipped at each others necks and got a clout from an adult, determined to restore a semblance of order to the night circus. The black pelts daubed with three stripes of ivory would disappear into the undergrowth only to reappear further on. The animals were preparing to forage in the fields and on the riverbanks. They were warming up for the night ahead.

From time to time, one of the badgers would wander close to our hide, snuffling the ground with its long snout, then turning to face us. The dark bands set with coal-black eyes sketched out melancholy smears. They were still on the move; we could make out the powerful plantigrade paws turned inward. In the French clay, their claws left small bear-like tracks that a certain lumbering race of humans, in its wisdom, identified as the tracks of vermin.

It was the first time I had ever been so still, hoping for an encounter. I scarcely recognized myself. Until now, from the Yakutia to Seine-et-Oise, I had run, adhering to three principles:

The unexpected does not pay house calls, it must be sought out everywhere.

Movement enhances inspiration.

Boredom runs less swiftly than a man in a hurry.

In short, I convinced myself that there was a link between distance and the importance of an event. I thought of stillness as a dress rehearsal for death. In deference to my mother, resting in the family tomb on the banks of the Seine, I roved about freneticallythe mountains on Saturday, the seaside on Sundaywithout paying attention to what was going on around me. How do journeys spanning thousands of kilometers lead one day to lying in the tall grass with your chin propped on the edge of a ditch?

Next to me, Vincent Munier was taking photographs of the badgers. The mass of muscle beneath his camouflage clothes blended into the vegetation, but his profile was still visible in the half-light. His face, all sharp edges and long ridges, seemed to be sculpted for issuing orders; he had a nose that Asians mocked, a carved chin and soft eyes. A gentle giant.

He had talked to me about his childhood, his father taking him to a hide beneath a spruce tree to witness the flight of the kingthe capercaillie; the father teaching the son the promise of silence; the son discovering the rewards of nights spent lying on the frozen ground; the father explaining that the appearance of an animal is the greatest gift life can give to those who love it; the son setting up his own hides, discovering the secrets of the world unaided, learning to frame a nighthawk taking wing; the father discovering the sons artistic photographs. Munier, lying next to me, had been born in the mists of the Vosges. He had become the greatest wildlife photographer of his time. His peerless photographs of wolves, bears and cranes were sold in New York galleries.

Tesson, Im taking you to the forest to see badgers, he had said to me, and I had accepted, because no one refuses an invitation from an artist in his studio. He did not know that Tesson meant badger in Old French. The word is still common in the vernacular of western France and Picardy. It originated as a deformation of the Greek