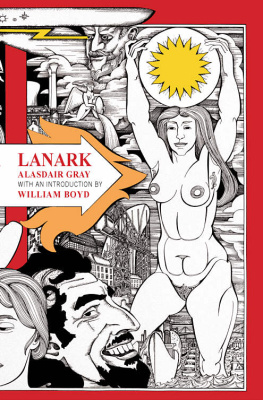

LANARK A LIFE IN FOUR BOOKS by

Alasdair Gray With an introduction by

William Boyd

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Readers develop unique histories with the books they read. It may not be immediately apparent at the time of reading, but the person you were when you read the book, the place you were where you read the book, your state of mind while you read it, your personal situation (happy, frustrated, depressed, bored) and so on all these factors, and others, make the simple experience of reading a book a far more complex and multi-layered affair than might be thought. Moreover, the reading of a memorable book somehow insinuates itself into the tangled skein of personal history that is the readers autobiography: the book leaves a mark on that page of your life leaves a trace one way or another.

The history of my reading of Lanark is exemplary in this regard typically complex. Twenty-five years ago I was paid to read Lanark by the Times Literary Supplement (I forget how much I received 40?) and the review duly appeared in the issue of 27 February 1981, entitled The Theocracies of Unthank. It was a long review, some two thousand words, leading off the fiction section that week, and it shared its page with a short poem by Paul Muldoon and an advertisement for Heinemanns spring list (Catherine Cookson, R.K. Narayan and Violet Powell, amongst others).

Looking back now it seems even more interesting that I came to review Lanark Alasdair Grays first novel a month after my own first novel, A Good Man in Africa , had been published. A Good Man in Africa had been reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement on 30 January that year, somewhat patronisingly (engaging, amusing), by someone called D.A.N. Jones, in a review that was one-third the length of my review of Lanark . However, I can detect no trace of professional jealousy, bitterness or chippiness in my analysis of Grays novel. Indeed, as a tyro novelist myself, I was flattered to be asked to review it at such length (by the then fiction editor of the TLS , Blake Morrison). I still have the diligent notes I made on that first reading they run to three and a half closely written pages (I have tiny, near-illegible handwriting). Clearly Lanark had already been designated an important novel by the TLS (even now it would be virtually unheard-of to grant a full page to a first novel) and it had been decided to give it due prominence.

Why was I asked to review it? I was already an intermittent reviewer of fiction in the TLS but I suspect that the Lanark commission arose because of two factors my nationality (Scottish colonial version) and because I knew the city of Glasgow, having spent four years there at university. But Blake Morrison could have had no idea, I think, that I had heard of Lanark long before he gave me the opportunity to read it.

In the early seventies (197175, to be precise), when I was studying for my MA degree at the University of Glasgow, there was occasional talk of Lanark amongst my circle of friends. Alasdair Gray was someone known to me by sight (we had mutual friends) and by reputation as a painter and muralist. Doubtless we drank in the same pub The Pewter Pot in North Woodside Road from time to time but I dont remember ever meeting him properly. However, Lanark had something of the whiff of legend about it, even then: it was reputed to be a vast novel, decades in the writing, still to see the light of day. Rather like equally heralded masterworks-in-progress, such as Truman Capotes Answered Prayers or Harold Brodkeys Runaway Soul, Lanark was talked about as an impossibly gargantuan, time-consuming labour of love, a thousand pages long, Glasgows Ulysses such were the myths swirling about the book at the time, as far as I can recall.

And so, finally, to have Lanark in my hand a few years later was something of a shock: it was indeed long, five hundred and sixty pages, and it bore Grays highly distinctive black and white drawings on the cover and inside. My abiding sensation as I began to read was one of intense and excited curiosity.

One final anecdotal digression to do with the tangled skein. It is unusual, as a young novelist/critic, to possess some years of apocryphal familiarity with a novel you are sent to review. Even more unusual, in the case of Lanark , was that I was also familiar with its publisher, Canongate then a very small, Scottish, independent publisher almost wholly unheard-of outside Edinburgh literary circles. I knew about Canongate because I had met its then owner/publisher, Stephanie Wolfe-Murray.

In the early summer of 1972 (aged twenty) I was living alone in my parents isolated house in the Scottish borders about three miles from the town of Peebles. I was working as a kitchen porter in the Tontine Hotel in Peebles trying to earn some money to pay for a trip to Munich (where my German girlfriend lived). Not owning a car or a bicycle, I used to hitchhike to and from work. I was quite often given a lift by a young woman who drove a battered Land Rover (she often drove this Land Rover in bare feet, I noticed, a fact that added immeasurably to her unselfconscious, somewhat louche glamour). This was Stephanie Wolfe-Murray, and she lived further up the valley in which my parents house was situated. In the course of our conversations during the various lifts she gave me I must have told her I suppose about my dreams of becoming a writer. She told me in turn that she had just started up (or was in the process of starting up) a publishing house in Edinburgh, called Canongate. I filed this information away (thinking it might be useful). I have never met or seen Stephanie Wolfe-Murray since that summer of 1972 (I did get to Munich, though, in time for the Olympics and the Black September terrorist disaster) and Im wholly convinced she has no memories at all of the Tontine Hotels temporary kitchen porter to whom she was giving occasional lifts that summer but for me it was a strange moment to see Canongate Publishing on the title page of Lanark and realise the unlikely connection and stranger now to think that Lanark was the book that put Canongate squarely and indelibly on the literary map.

Such are the complexities of personal history that enfold the simple reading of a book. I havent read Lanark since that 1981 review (though I have read and reviewed other of Alasdair Grays novels and stories and have since met him on a few occasions) and to re-encounter a closely-read and greatly admired novel twenty-five years on is not necessarily to be encouraged I abandoned a recent re-reading of Catch-22 because my growing dismay was seriously tarnishing the memories of my rapt late-adolescent engagement with what I thought was one of the great novels of all time. However, revisiting Lanark was both a fascinating and a revealing experience. When I reviewed the book in 1981 it had no reputation; now its immense freight of reputation is impossible to ignore.

What can one say about Lanark that hasnt been said already (most eloquently by Gray himself, in his tailpiece How Lanark Grew)? Re-reading my review I can see how much I enjoyed the novel, but my appreciation was not unequivocal. I particularly relished the two books about Duncan Thaw in Glasgow but I was less taken with the allegorical counterpoint of the eponymous Lanark in the city of Unthank. I wrote: Thaws story Books One and Two forms a superb, self-contained realistic novel about a disturbed childs education and his uneven growth towards manhood. But the Unthank sections drew less praise: The bizarremachinery of the world of fable reasserts itself ; The final scenes of Lanarks rise to power (he becomes Provost of Unthank) are amongst the least successful parts of this long and demanding novel Lanark is, in effect, made up of two novels, one traditional and naturalistic, the other a complex allegorical fable. My conclusion, though, was genuinely positive: For all its unevenness Lanark is a work of loving and vivid imagination, yielding copious riches, especially in the two central books of Thaws life which, had they been presented on their own, would surely have been hailed as a minor classic of the literature of adolescence.

Next page

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS