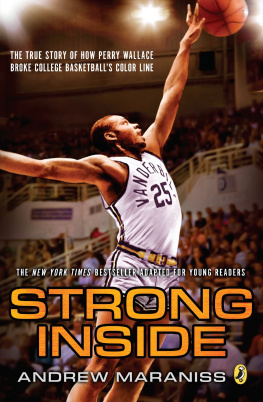

Andrew Maraniss - Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South

Here you can read online Andrew Maraniss - Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Vanderbilt University Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South

- Author:

- Publisher:Vanderbilt University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

2015 RFK Book Awards Special Recognition

2015 Lillian Smith Book Award

2015 AAUP Books Committee Outstanding Title

Based on more than eighty interviews, this fast-paced, richly detailed biography of Perry Wallace, the first African American basketball player in the SEC, digs deep beneath the surface to reveal a more complicated and profound story of sports pioneering than weve come to expect from the genre. Perry Wallaces unusually insightful and honest introspection reveals his inner thoughts throughout his journey.

Wallace entered kindergarten the year that Brown v. Board of Education upended separate but equal. As a 12-year-old, he sneaked downtown to watch the sit-ins at Nashvilles lunch counters. A week after Martin Luther King Jr.s I Have a Dream speech, Wallace entered high school, and later saw the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts. On March 16, 1966, his Pearl High School basketball team won Tennessees first integrated state tournamentthe same day Adolph Rupps all-white Kentucky Wildcats lost to the all-black Texas Western Miners in an iconic NCAA title game.

The world seemed to be opening up at just the right time, and when Vanderbilt recruited him, Wallace courageously accepted the assignment to desegregate the SEC. His experiences on campus and in the hostile gymnasiums of the Deep South turned out to be nothing like he ever imagined.

On campus, he encountered the leading civil rights figures of the day, including Stokely Carmichael, Martin Luther King Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer, and Robert Kennedyand he led Vanderbilts small group of black students to a meeting with the university chancellor to push for better treatment.

On the basketball court, he experienced an Ole Miss boycott and the rabid hate of the Mississippi State fans in Starkville. Following his freshman year, the NCAA instituted the Lew Alcindor rule, which deprived Wallace of his signature move, the slam dunk.

Despite this attempt to limit the influence of a rising tide of black stars, the final basket of Wallaces college career was a cathartic and defiant dunk, and the story Wallace told to the Vanderbilt Human Relations Committee and later The Tennessean was not the simple story of a triumphant trailblazer that many people wanted to hear. Yes, he had gone from hearing racial epithets when he appeared in his dormitory to being voted as the universitys most popular student, but, at the risk of being labeled ungrateful, he spoke truth to power in describing the daily slights and abuses he had overcome and what Martin Luther King had called the agonizing loneliness of a pioneer.

Andrew Maraniss: author's other books

Who wrote Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.