The blast strips the illusion of peace from the fields in an instant and automatic gunfire starts to crackle around the reporter. Hes 40 but vaults like a teenage gymnast into an irrigation ditch and presses himself to the earth as the Danish troops pinpoint the source of the attack. Someone shouts suicide bomber, then insurgents hidden in three compounds open up at the patrol, drawing heavy suppressing fire from the armoured cars on the cliff top above.

He looks down at himself and is seized by the horror of discovery, not of a bullet hole or shrapnel wound but of thick tracks of human excrement smeared up his boots, legs and waist. His first time under fire and he lands in the Talibans toilet, a small victory for the assailants before they die in precision bombardments. Fighting off revulsion rather than fear, he wonders if this gruesome landing hasnt saved him the trouble of fouling himself.

Zabi the Afghan interpreter is crouched on the other side of the ditch looking almost bored. His eyes light up with interest as he studies the daubed journalist.

Shit happens, he says with a grin.

Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired, signifies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and not clothed.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

CONTENTS

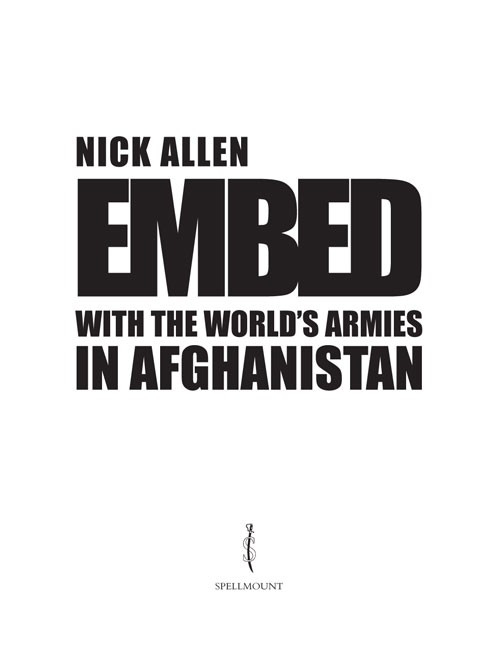

I cant say exactly when I decided to throw in a well-paid, secure job with my employer of eight years, the German Press Agency dpa, and go to Afghanistan to research this book; most likely after I blew a gasket trying to get out of Kabul in July 2007 to cover the storming by commandos of Islamabads militant Red Mosque.

The foreign press corps based in the Pakistani capital had been tracking the confrontation for months and we knew the authorities would eventually move to crush these shoots of Talibanization in the heart of the city. That summer, a few of us left the country to follow other stories or risked a vacation, or like me were traipsing round the Talibans original homeland when the final chapter of the mosque drama unfolded. When a faulty altimeter prompted PIA to cancel my flight back to Islamabad the day before the storming operation, it was too late to drive via the Khyber Pass. I arrived on a UN plane the next afternoon when the assault was winding down and the government lies about numbers of bodies had begun. There was still plenty of work to do but as any news reporter will tell you, missing the main event after a long build-up stings to the core.

The decision to quit was also partly born of fatigue and frustration at sitting at a computer for long months cranking out hundreds of news wire stories about Pakistans murky political intrigues and the confrontation between then President Pervez Musharraf and the judiciary. And I remember regretting that so much material from the weeks I spent embedded with US forces in Afghanistan since December 2006 would go unused after my agency stories were filed, and would languish in faded notebooks in a box somewhere; or like my financial records for the previous ten years, be consumed by invading legions of termites in a dark cupboard in my home in Islamabad.

Perhaps the decision to delve deeper into the soldiering life had been unconsciously sealed with a flash from the night sky over Afghanistans Zabul province that June. I was lying on my cot at a tiny Romanian outpost, gawping at the night sky and thinking the words this trip will change your life when a shooting star arced brightly overhead. An over-scripted movie moment maybe, but true nonetheless. A month later, after the mosque story had run its course, I handed in my notice and mentally if not physically embarked on this project. It took me until November to fully extricate myself from the agency job and the Pakistan story, but it eventually happened and that winter I embedded again with US and Polish forces in eastern Afghanistan.

By the time I wound up the active research nineteen months later I had been what the media and militray call embedded with thirteen foreign contingents for longer or shorter periods, a day in the case of the Swedes, to five months with various US units over nine embeds. The number of separate embeds altogether was over 20, with a few running into others and morphing into something different, so its hard to say how many I did and not so important. I know people who spent far more time in the system, including an American film maker who did an entire 15-month tour with one infantry company and then more time with the Special Forces. The idea was never to embed longer and with more armies than anyone for the sake of credibility. To do so would have been meaningless.

The idea was always to show something of the soldiers deployed lives, but I had many notions about what would result from my visits mainly to the southern and eastern provinces and also a few places in the central and northern regions. Regrettably, I never got to the west and I missed some chief troop contributors to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), notably the German contingent. (But I did get to enjoy their well-stocked bar in Mazar-e-Sharif).

Various project impulses included a fleeting idea of an irreverent travelogue penned from inside the US military machine until I got booted out (working title A Year in Uncle Sams Back Passage), and trying to draft a comprehensive account of military operations in recent years from the ordinary soldiers point of view. Eventually I came full circle to where it was always heading: a front row seat in the front lines and backwaters of Kandahar, Helmand, Kunar, Khost and other provinces, living among ordinary servicemen and women who were doing remarkable things far from home. And I was faced with much of the drama, boredom, tragedy and farce that seem to characterize every war ever fought here or anywhere else.

My thanks go to the public affairs and ministry officials with whom my requests to visit their contingents found resonance and who helped make it happen. As it turned out, those who proved least receptive were my own countrymen in Whitehall and Lashkar Gah. After jumping through hoops and passing vetting rounds to be approved as a reporter and/or book author, my efforts to embed with UK forces in Helmand over two years to tell something of their story came to nought. The only explanation I received from the MoD was that some people on the media selection panel were uncomfortable with book authors after publication of British journalist Stephen Greys Operation Snakebite . But I was fortunately still able to embed with the Royal Gurkha Rifles for six weeks in Kandahar and mingle with the Brits in Helmand while embedded with the Danes, Estonians and US Marines. I thank every member of the military who assisted or simply put up with my presence and every Afghan who welcomed me in his country or missed me when he shot.

I dont presume to have captured the functional essence of the armies I visited but with some events and experiences that individual units went through I feel pretty close to the mark. I still get mails from soldiers I met with mostly kind words about extracts they read or video clips and photos they saw. That is almost worth the effort in itself, since embedded reporters are hardly a desired appendage to a platoon; we are generally regarded as excess baggage and a liability. Alongside everything else that happens in these pages, there is hopefully a taste of what it is like to be that initially faceless media man who is thrust upon the troops from above. To some soldiers our presence is uncomfortable and unwelcome knowing what some journalists look for I would feel the same in their place. But I was always aware of the trust this afforded me and resolved not to abuse it. I have been party to conversations that would be incorrectly understood and look outrageous in print, without hearing the audible irony of their deliverance or sharing the confusion or anger at events that sparked them. I have nonetheless used elements of such exchanges anonymously since they are important in their own right and should simply be heard. In some places names have been changed to protect individuals, while others have been left as they are, at the risk of my receiving some prickly mail when all is said, read and done.

Next page