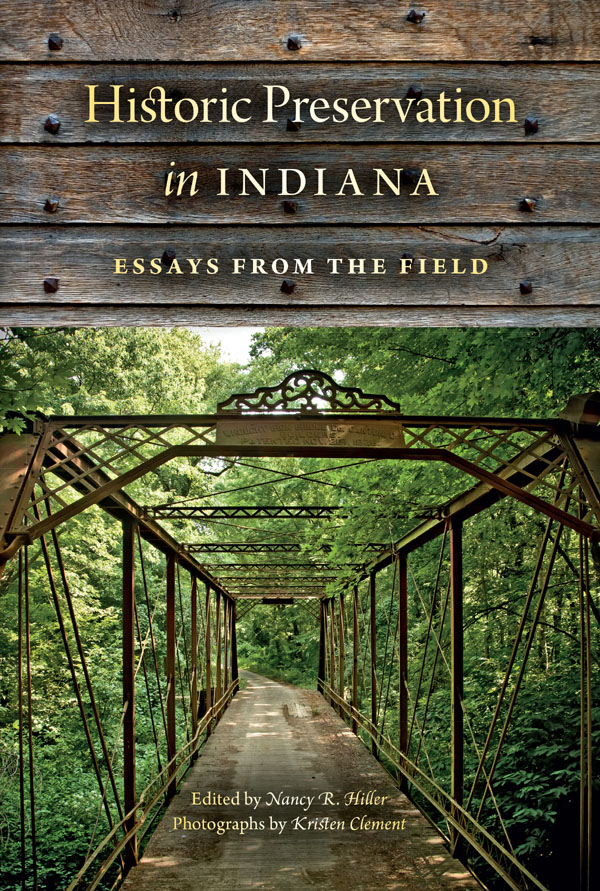

HISTORIC PRESERVATION IN INDIANA

Historic Preservation in INDIANA

ESSAYS FROM THE FIELD

Edited by Nancy R. Hiller

Photographs by Kristen Clement

an imprint of

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington & Indianapolis

This book is a publication of

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

2013 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.481992.

Manufactured in the

United States of America

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Historic Preservation in Indiana : essays

from the field / edited by Nancy R. Hiller;

photographs by Kristen Clement.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references

ISBN 978-0-253-01046-9 (paperback :

alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-253-01067-4

(ebook) 1. Historic preservation

Indiana. 2. Historic buildings

Conservation and restoration Indiana.

I. Hiller, Nancy R., editor.

2013008453

1 2 3 4 5 18 17 16 15 14 13

Theres an actual relationship, when you go into a building thats very beautiful, and its awe-inspiring, and its uplifting. It elevates the soul.

FATHER MICHAEL WALKER ,

Joy of All Who Sorrow Orthodox Church, Indianapolis

Contents

Foreword

Duncan Campbell

I have always been struck by the passion and fervor of historic preservationists and environmental activists. They have a thirst, an appetite for their respective causes that sustains their advocacy and fuels their zeal. This is as it should be. After all, there is a lot at stake: cut down a Sequoia or tear down Penn Station and they are gone forever. There is little room for compromise among combatants and lots of room for disappointment and anger when your cause is lost. The prize is the nations real estate, and there is precious little of it left to go around.

Of course there are many important causes, each with its champions. Elections, business deals, and even sporting events can also involve high stakes, and their respective advocates, whether campaign workers, CEO s, or soccer fans can be just as fervent. In contrast, though and this is not to suggest that these other activities dont matter there will always be another election, another business opportunity, and another game: an opportunity to even the score, tweak the market, field another team. There will never be another Penn Station or stand of Sequoias.

What distinguishes environmental and historic preservation advocates from other activists is that the threats they battle have irrevocable results. A highway cut or razed building can be absorbed emotionally, but the place will never be the same. The tree-hugger and the building-hugger understand this, and though not everyone agrees that protecting a landmark and defending a forest are quite the same thing, each proponent in his or her own way is fighting the same battle: the battle for place. When I ask students why they want to study historic preservation, or what first motivated them toward an interest in historic sites, invariably their responses describe a meaningful experience of a place: a grandparents house, a trip to Williamsburg, a favorite neighborhood. Natural resources students convey similar experiences: a first glimpse of Yosemite, camping in a national forest, a trail construction stint in a state park. Both say they have experienced the loss of a place meaningful to them.

My own path to historic preservation was circuitous, and perhaps not typical, but my motivation to protect both the natural and built environments is predicated on a respect for the importance of place that was constructed from a childhood enjoyment of nature, trips to historic sites, reading history, old house carpentry, a preservation graduate degree, consultant and advocacy work, and a stint as a university professor overall, a lot of time observing, caring for, studying, and just being in the presence of irreplaceable places. Coupled to this is another aspect of my own character that I see shared by other preservers: a desire to do right, to defend places of value. For many, and I have witnessed it among students as well as more seasoned preservation believers, it is an ethical commitment consistent with a closely held sense of right and wrong. Protecting and saving meaningful places is the right thing to do.

The defense of special and historic places, whether wild natural landscapes or our most meaningful constructions, is challenging on several fronts. In both arenas choices are complex and undertakings can be long and arduous, often taking many years; in a real sense, the job is never done. As a consequence, we commonly refer to environmental or preservation advocacy as movements, ideas whose manifestations persist over several generations, engage high stakes battles, and command from their followers a shared sense of what is right. But what makes this possible? What is the ingredient that enables an idea about protecting place to be important enough to sustain itself as a movement, to engender passion in its advocates?

I suggest that we are the ultimate beneficiaries of saving meaningful places. We do it for ourselves, our communities, our fellow human beings. People experience place. We get something in return for being in meaningful places, something I think of as sustenance, though it may be closer to redemption. I believe John Muir, the naturalist, thought of it as salvation.

In the fall of 2009, filmmakers David Duncan and Ken Burns aired the public television series The National Parks: Americas Best Idea, which conveyed in their pioneering style the developmental history of our national park system. In the telling, the eloquence and fervor of naturalist and Sierra Club founder John Muir emerged as a key part of the story, revealing perhaps for the first time to many viewers the important advocacy role that Muir assumed in motivating President Theodore Roosevelt to establish our system of national parks.

Environmentalists, of course, have long cherished John Muirs capacity for rapture in the presence of wild places, and his moving essays recounting his own explorations are well known. Perhaps less well known is his emotional defense of the wilderness. I encountered his writing in my twenties, while living in California and having the occasion to hike and camp in the Sierra Range, and I credit him as one who helped motivate me toward my eventual career in historic preservation, even though, to my recollection, he never mentions it by name. Many years later, reading his letters, I discovered his familiar quote, Nothing dollarable is safe, however guarded.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.481992.