Additional material copyright 2013 by Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

No claim is made to material contained in this work that is derived from government documents. Nevertheless, Skyhorse Publishing claims copyright in all additional content, including, but not limited to, compilation copyright and the copyright in and to any additional material, elements, design, images, or layout of whatever kind included herein.

All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62087-475-2

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Several years ago I received a phone call from a woman who invited me to come and see her recent preservation project. She was so proud of her efforts in preserving a historic family farmhouse that she suggested I bring my camera, as it was likely that I would want to write an article about her project. She hinted that she could even envision people wanting to see the house to learn more about the methods she used.

I could hardly refuse such an offer. I grabbed my camera and began the drive. I was somewhat familiar with the address as it was located in an area of Indiana where I had spent considerable time. I tried to picture the house in my mind, but rural Indiana has its fair share of old farmhouses. I simply could not remember it. Perhaps, I thought, I would be able to place it once I arrived at the site.

I was absolutely correct. I immediately recognized the location. It was a site that I had admired many times. The house had been in good condition when I last saw it, a well-maintained wood clapboard farmhouse with a beautifully simple front porch. Now, however, it took some imagination to even recognize the house. Seeing the house in its current state, my heart dropped almost as far as my jaw. I must have looked shocked and stunned as I stepped out of my car with my eyes fixated on the house. I barely noticed the smiling woman approaching me. Struggling to utter a response, I asked her to walk me through the project. She was proud to do so.

She provided a commentary as we walked. My car was now parked in the location where the house had stood for more than 100 years. The house was moved back about fifty feet so a car careening off the road would not hit it. According to the owner this was the best way to protect the house. A new block foundation supported speckled brown and tan brick that now covered the entire wood clapboard house. The woman had tried to paint the house recently, but the paint did not seem to stick. Covering the house in brick would eliminate the need to paint. The original quaint front porch was totally gone. It was replaced with a shiny new vinyl substitute. The new porch was not even close to being the same size or shape as the original. She maintained that the old wood porch had been exposed to the elements and claimed that this new vinyl porch would last forever. All the original windows were replaced with inexpensive vinyl windows. She said that the old windows had been in good condition, but she wanted to be energy efficient, even though the replacement was extremely costly. Architectural brackets under the eaves were removed. The chimney was gone. The house was no longer the house I had appreciated. It was not even the same housethis preservation project had eradicated it.

While I had never viewed the inside of the house, the level of intervention on the interior was equally as shocking. All the lath and plaster was removed in favor of drywall. All hardwood floors were covered with carpet. Some of the wide oak trim was now painted, while the rest of the trim had been destroyed when the lath and plaster was ripped out and was replaced with pine. All light fixtures were removed and replaced with contemporary alternatives. The oak staircase was now painted white. The owner remarked at how much brighter the stairs were now. Particularly disturbing was the kitchen, where all the original cabinetry had been replaced cabinets which had been hand-made from trees harvested on the farm. The owner validated the replacement by saying there were too many coats of paint on the cabinets, and that there was no way to remove the paint. Old bedroom closets were abandoned for closets that used sliding doors. The old, heavy and solid interior doors were replaced with new, flimsy and hollow doors. Even though the old claw-foot bathtub was reused, it now sat in the backyard. Its new use? A large flower pot.

Possibly more shocking than the transformation was the owners pride in thinking that this was a respectable preservation project of the highest quality. She sincerely believed that she had preserved and protected a historic farmhouse. But in the process of doing so, she replaced everything that made the house historic and unique. She replaced everything that had defined the house. Inferior materials replaced quality historic materials that would cost a fortune today if one could even find them. There placed quality historic materials that would cost a fortune today if one could even find them. The only historic elements remaining were some trusses, the framing and about half the floor joists. This was now a brand new house. Virtually every decision that had been made had been the wrong decision. Unnecessary expenses were unbelievable. It was all too apparent that a misunderstanding of what it means to rehabilitate or restore historic architecture had been a costly misunderstanding. I made a feeble attempt to explain to the owner how her approach may have not been the best approach. But the damage was doneshe had preserved the house to death. I thanked her for the tour and drove off bewildered, but also a bit wiser.

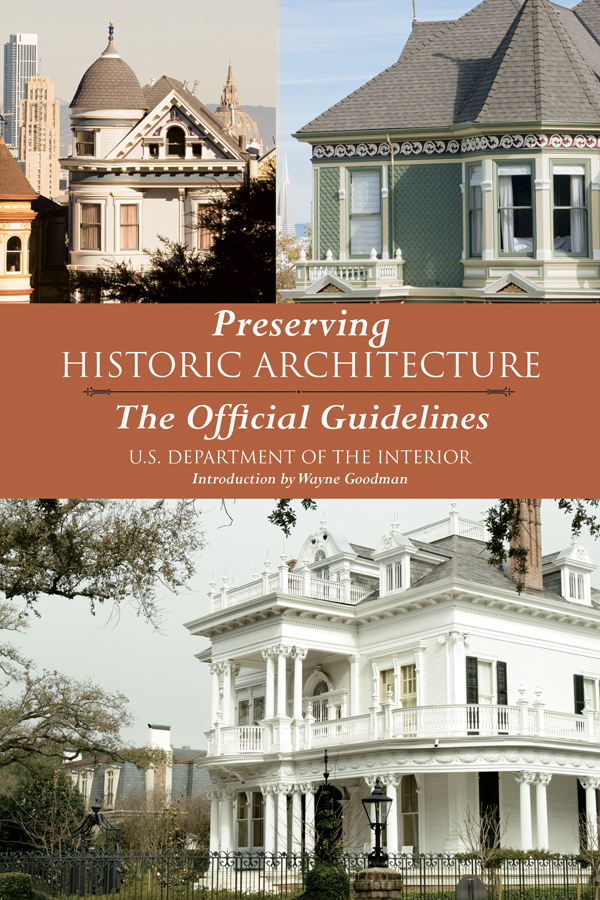

People with good intentions and sincere motives sometimes make poor decisions on how to preserve historic buildings. There is a distinctly human element inherent in preservation. Historic preservation enhances the way we view our communities and demonstrates personal and collective pride. Historic resources are not static, outdated or obsolete monuments to the past, but are opportunities to be utilized as homes, community centers, housing or businesses. Preserving these resources is both a science and an art. Understanding chemical compositions can be critical when removing paint or cleaning masonry. Using the wrong mortar mix can literally cause a brick building to crumble. Yet there is an art in how a modern-day craftsman rehabilitates a dilapidated storefront so it reflects an appropriate appearance and is sympathetic to its surroundings. Artistic design is employed when constructing an appropriate addition to a historic building. Preservation is an interdisciplinary recipe of history, art and chemistry, with a touch of culture and physics.

Preservation embodies much of what makes communities strong. It fosters a responsible use of our environmental resources, creates jobs, rebuilds neighborhoods, elevates investment and stabilizes and increases property values. Good preservation philosophy is the best way to apply our heritage in a way that leverages profit through pride, choosing reuse over ruin. It is essential that projects utilize the correct approach, since the best intentions to rehabilitate or restore a historic building can lead to unintended consequences. Such avoidable mistakes not only compromise the integrity of a resource, but also cause expensive and irreparable damage.