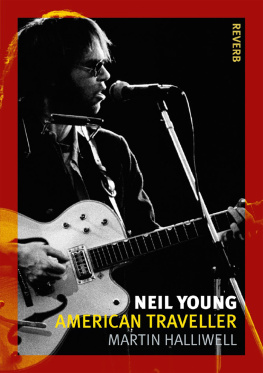

NEIL YOUNG

The Reverb series looks at the connections between music, artists and performers, musical cultures and places. It explores how our cultural and historical understanding of times and places may help us to appreciate a wide variety of music, and vice versa.

reverb-series.co.uk

Series editor: John Scanlan

Already published

The Beatles in Hamburg

Ian Inglis

Brazilian Jive: From Samba to Bossa and Rap

David Treece

Easy Riders, Rolling Stones: On the Road in America, from Delta Blues to 70s Rock

John Scanlan

Heroes: David Bowie and Berlin

Tobias Rther

Jimi Hendrix: Soundscapes

Marie-Paule Macdonald

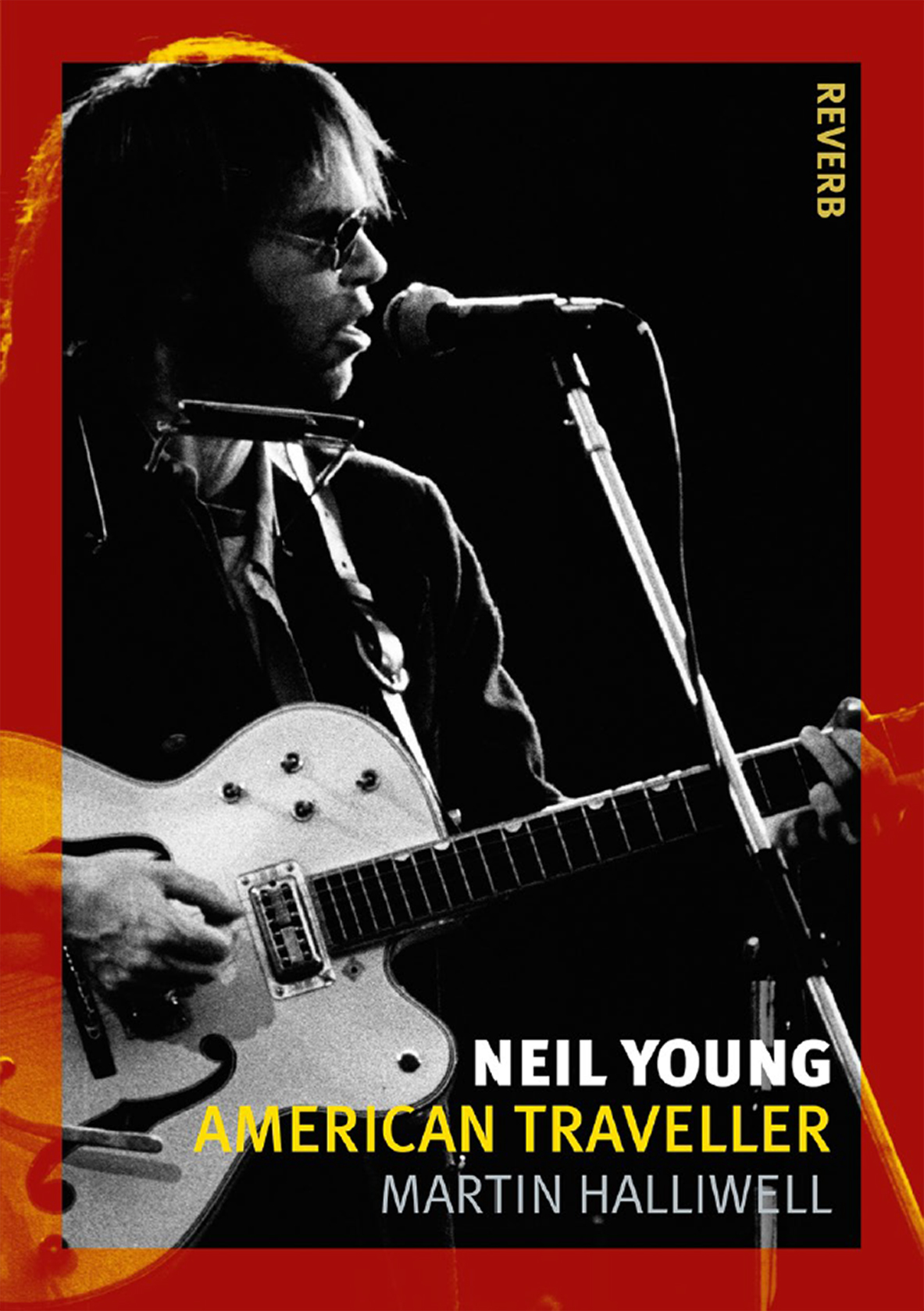

Neil Young: American Traveller

Martin Halliwell

Nick Drake: Dreaming England

Nathan Wiseman-Trowse

Remixology: Tracing the Dub Diaspora

Paul Sullivan

Tango: Sex and Rhythm of the City

Mike Gonzalez and Marianella Yanes

Van Halen: Exuberant California, Zen Rocknroll

John Scanlan

NEIL YOUNG

AMERICAN TRAVELLER

MARTIN HALLIWELL

REAKTION BOOKS

To Alex

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2015

Copyright Martin Halliwell 2015

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780235493

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The three most listened-to albums of my undergraduate years spent in Devon in southwest England were Freedom, Ragged Glory and Harvest Moon. These were widely hailed as Neil Youngs return to form after the uneven studio experiments of the 1980s when he was unhappily on the Geffen record label, and I felt lucky to be initiated into three dimensions of his music the conceptual richness of Freedom, the heavy guitar grind of Crazy Horse on Ragged Glory and the lyrical nostalgia of Harvest Moon but also saddened that this was not twenty years earlier, when the silver spaceships of Youngs countercultural song After the Gold Rush might have transported me into a transcendent realm.

I often regretted that the year I was born, 1970, was not my coming-of-age year; that the increasingly corporate 1980s couldnt be traded in for the cultural vibrancy of the late 1960s; and that my student war (the Gulf War of 199091) did not harness the same energies of protest and creativity as the much longer war in Vietnam, even if it did spark Youngs emotionally charged performances on his 1991 tour with Crazy Horse. Born a month after the Kent State University shootings by the National Guard of 4 May 1970 and the writing of Youngs iconic protest song Ohio, I often felt like I was living at one remove from history, especially when the French theorist Jean Baudrillard was proclaiming that the Gulf War was only a virtual media spectacle for most people around the world. I even wondered how things might have been had I grown up in Seattle, where I lived as a small child in the early 1970s when my father was seconded there with Boeing. Too young to be aware of the gravity of the Watergate scandal or to know that Youngs roadie Bruce Berry had been found dead from a heroin and cocaine overdose on my third birthday, I was more interested in hanging out with Disney characters in Anaheim or seeing totem poles in Vancouver.

A decade on, and back in the UK as a secondary-school kid in the East Midlands at a time when both progressive rock and punk had worn themselves out, I wanted to believe that being educated in the Pacific Northwest would have connected me to a more vibrant and politicized music scene than anything that was available in Britain. Of course, given my age and Seattle location, I would be much more likely to have been a Queensrche groupie or a Nirvana dropout than a devotee of Californian folk rock, even though Young performed live in Seattle four times between 1989 and 1992 (coinciding with my undergraduate years) and recorded his Mirror Ball album there with Pearl Jam in 1995.

For the most part, being British did not help my sense of connectedness, and perhaps led me to focus on American Studies as a graduate student in the mid-1990s, by which time I had filled in my missing years with most of Youngs 1970s back catalogue. Two memorable moments from back then are waking up blearily at my parents house halfway through the extended guitar solo of Cortez the Killer to find that a cassette of Young and Crazy Horses 1975 album Zuma had been playing on loop all night, and, a year later, going vinyl shopping with friends in Nottingham and triumphantly discovering a solitary German-import CD of Youngs arguably most significant album, On the Beach (otherwise unavailable on CD at that time), in a now sadly closed record store, Selectadisc (19662009). There are many instances since when Youngs music has been bound up with personal experiences in which place and time have been particularly resonant. My other major Canadian musical influence, Rush, rarely evoke geography in the same way, other than the occasional critique of suburban life (on their 1982 track Subdivisions) or reminiscing about growing up by the shore of Lake Ontario (on Lakeside Park from 1975). Rushs lyricist Neil Peart is more often interested in metaphysical abstractions, scientific themes and alternative cosmologies than a rootedness in distinct North American locations. In contrast, on listening to Neil Youngs music I discover moments and spaces that are both real and mythical.

I am very aware that my autobiographical sense of elsewhere colours my response to songs such as Helpless and Dont be Denied, through which Young reflects on his childhood and school years in Ontario and Manitoba. And I am not a unique case. This is as true for the majority of listeners in Canada, the United States and around the world, and Youngs interest in old Spanish American and Native American cultures stretches that feeling of elsewhere for many others. Sometimes, as is the case on Zuma, Youngs topographies are both actual (Zuma Beach, north of Malibu, where Young was resident on Sea Level Drive in 1974) and lost in time (the demise of Moctezuma IIs Aztec Empire in the early sixteenth century). And sometimes his meditation on place occurs between songs. For example, on two tracks written in the late 1960s, the apocalyptic city in the smog of LA contrasts with the bittersweet title track of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, on which the migrant singer dreams of being back home where it is cool and breezy. Distinct places can vanish into nowhere spaces and then re-emerge: Los Angeles is both real and nowhere in these two songs, while Youngs childhood home, Omemee, is not actually a town in north Ontario, as the opening line of Helpless describes it, but only 80 miles from the urban centre of Toronto. Young is not studiously historical or geographical in his research and at times he indulges in romanticism, but he is very often conscious of this, most obviously on his fantasy song Pocahontas (1979), in which the musician-songwriter, the Powhatan and iconic actor Marlon Brando (a champion of Native American causes) sit around the campfire to reflect on the astrodome and the first tepee. Often bound up with journeys and road travel, Youngs geographies span the Americas past and present, north and south, rural and urban in an expansive manner that is rare among recording artists.