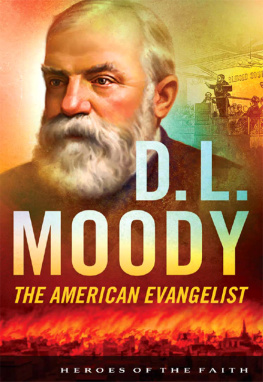

D.L. Moody

D.L. Moody

Faith Coxe Bailey

MOODY PRESS

CHICAGO

Original title D. L. Moody;

The Valley and the World

C OPYRIGHT 1959, 1987 BY

T HE M OODY B IBLE I NSTITUTE

OF C HICAGO

ISBN 0-8024-0039-6

47 49 50 48

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

Y OU COME BACK HERE, Dwight Moody! What in the world do you mean? Set me to work and then just walk off! Young D.L. Moody turned and saw his brother George drop his ax to the ground. George sputtered again, You cant get away with it. You set me to work like I was a hired hand. Then you stand around and.

And organize, D.L. said, grinning.

Organize! Huhanother word . for pushing work off on another fellow. I heard you talk before, Dwight. You grab that ax and start chopping.

In another moment, his big brother would start after him. But it was too nice a day for a real squabble. So D.L. walked toward the woodpile, reluctantly. Ones enough for this job, he started to explain. You follow my system, George, and you.

Chop! George said.

For the next few moments there was no sound in the back yard of the Massachusetts farmhouse but the steady thud of ax on wood and the instantaneous splitting of pine. Overhead a bluejay rasped, and D.L. thought in irritation that the bird was mocking his sweat. When the jay scratched out a last remark, curving away over the trees, D.L. hated the bird for flaunting its freedom. He lifted his ax more slowly, slamming it down with force but no bounce.

Chop wood in the fall, he grunted, half to his brother, more to himself. Hoe corn in the spring. Pick beans in the summer. That aint no life.

George straightened up, pulling the sweat from his forehead with the back of his hand. Why dont you organize something better?

Sick and tired of being squeezed into this valley. Now the ax swung fiercely. Sick and tired. Up with the ax. Sick and, down with the ax, fiercely, tired.

You got growing pains. Youre but sixteen, Dwight. I had em too.

D.L. rested his ax, leaning on the handle. These growin pains are gonna grow me right off this farm and out of this valley and over them hills.

Youre too big for your breeches, Dwight.

He flung down his ax. Then Ill get me new breeches. Fancy ones. City ones. Not wood-chopping breeches. A chunk of pine splintered off from Georges ax and hit him sharply against the shins. He sidestepped but he didnt look down. Instead, he studied the low hills in the distance, as brown against the sky as the turkey gravy his mother was sure to serve at dinner. Crossly he flung the thoughts of his mother and the familys Thanksgiving dinner out of his mind. A man is only so much muscles and blood and brains, he told his brother. Its up to him what he makes out of that raw stuff. Well, Im gonna make something, something big. You wait and see.

It was Thanksgiving Day, 1853. Later at the table, young D.L. hunched up his shoulders, ducked his head and, protecting his plate with a curved arm, gave his full attention to the turkey, mashed potatoes, and squash. When he had almost come to the end of his second plateful, be began to listen to the conversation between his mother and his Uncle Samuel, up from his Boston shoestore for the holiday.

He comes up and stuffs himself fat on out victuals, he thought as his uncle belched behind his napkin. Then he goes back to the big city, shaking the dust of the road in our faces and thinking us all poor country relatives. The rings on his uncles hands glittered. If only be could get to that city on the other side of the hills, he could get rich too.

Uncle Samuel patted his mouth politely and belched again. I declare, Betsy Holton Moody, this pie of yours is richern Beacon Hill.

D.L. leaned down the table. Uncle Samuel, them folks on Beacon Hill, he began.

But his mother rapped the table. Dwight, your uncles plate. Pass it like a good boy.

D.L. paid no attention. Theyre all rolling in money, huh?

Dwight! Your uncle wants another piece of pie.

He handed down the plate and kept on talking. Im figuring on being rich some day, Uncle Samuel.

His mother drew in her breath, but his uncle beamed and nodded. Thats a good ambition. Its a free country, Dwight.

Im figuring on coming down to Boston.

Dwight. His mothers cheeks were getting pink, a sure sign of trouble ahead.

But Uncle Samuel clucked pleasantly. Now, Betsy, dreaming never hurt nobody.

So D. L. persisted. Right away.

Whats that!

The prongs of D. L.s fork drew a wild circle in mid-air. Figure you need a new hand to help out . with winter trade..

His uncles chair scraped the wood floor. Why, Dwight, boy, Id be happier than a clam at high tide to oblige you, but it just so happens.

I dont aim to work for you long, D.L. hurried on. Just till I get my bearings and decide what I really want. His uncle said nothing. The chair squeaked back and forth. Elatedly, D.L. thought, it must be settled. Easier than hed hoped!

Suddenly, across the table, Georges chin jutted out. You hire old Dwight here, and hell be running your store before you know it.

D.L.s chair shot back, and he grabbed for his brother. But George was halfway out of the room, his pie in his hand. From the doorway, he taunted, Watch out, Uncle Samuel. You watch out for old Dwight. Hell run the store right out from under you.

D.L. let him go, concentrating on his uncle. Strike a bargain, Uncle Samuel. Ill go back to Boston with you tomorrow. His uncle had to see he could not stay there on the farm, chopping wood for the rest of his life. You can hire me for less wagesn you pay anybody else. Thats a bargain.

His uncle said nothing as he pushed his chair back from the table, giving his napkin and his lap a little shake that spilled crumbs of turkey and stuffing to the floor. He belched. Im fullern a healthy hog, Betsy, he said ponderously. Then he turned to D.L. Settle down there, boy. I never struck no bargain. I reckon youll call me mean as goose grease, but the truth is theres no place in my Boston shoestore for you. You stay put right here in this valley and look after your widow mother.

But D.L. had caught hold of an idea and he was not going to be pried loose. Uncle Samuel could help him escape from the valley, and there was no reason why he should not. But later, when he faced his uncle out by the woodpile, his uncle made his reasons very plain. What about your mamma, Dwight? You got some obligation to Betsy, after all. The way shes brought up all of you. Why, you were but a four-year-old tyke when your papa died.

Id send money home, D.L. murmured.

As his uncle fiddled with his waistcoat buttons, his rings sparkled in the fall sun. D.L. could not take his eyes from them. Tisnt just your mamma, Dwight, that makes me say no. Tisnt just the way I feel about a country boy knowing his place and staying there. But, Dwight. His uncle puffed out his cheeks. Dwight, youre a hotheaded, unlearned young fool. Youre wild. Who pinned up the notice for the temperance meeting last month?

But.

Gathered up a crowd of hard-working farmers to hear the lecture and there wasnt no lecture at all.

Cant a fellow have some fun?

Fun and tomfoolerythats what your wildness is in the country. But the citys different. A hundred ways for a young fellow to go wrong. Especially one thats got a wild streak in his nature. Hed get out of hand. Disgrace himself.

D.L. interrupted. I could take care of myself.

and disgrace the good name of the Holton Shoestore. Uncle Samuel puffed out his cheeks again and then sucked them in. No, sir, Dwight. Youre bright as a button, but youre headstrong. You stay right here in the valley and grow up to be a sensible farmer.