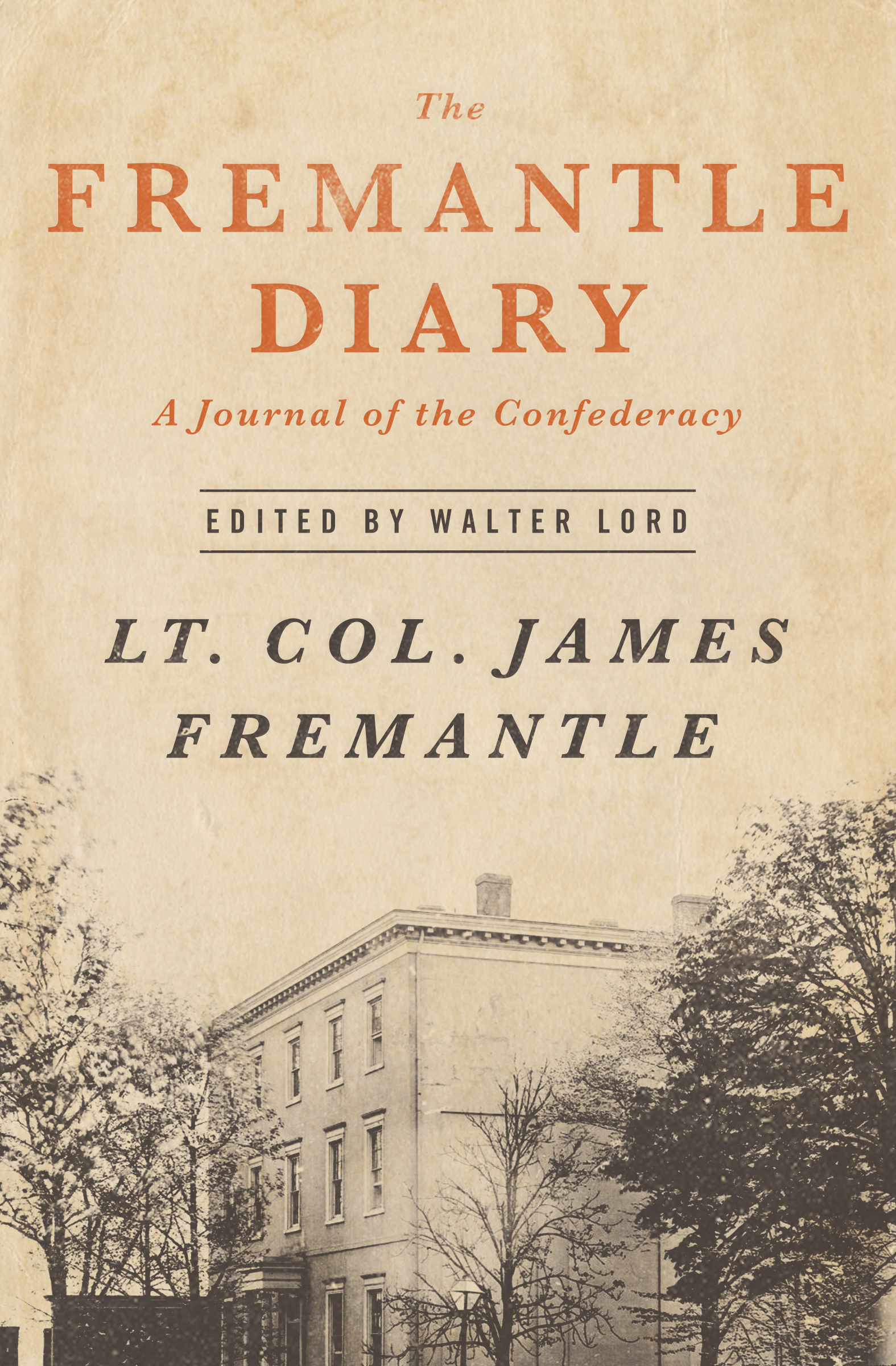

The Fremantle Diary

Being the Journal Of Lieutenant Colonel Arthur James Lylon Fremantle, Coldstream Guards, on His Three Months in the Southern States

Editing and Commentary by

Walter Lord

Editors Introduction

COLONEL FREMANTLE OF ENGLAND was ensconced in the forks of a tree not far off, with glass in constant use, recalled General John B. Hood. The occasion was the Confederate High Commands conference in a Gettysburg meadow early on the second day of the Civil Wars climactic battle. General Hood was reminiscing some twelve years later in a letter to the Southern Historical Society, but he still remembered vividly the ubiquitous, oddly dressed Englishman who peered down from the tree with his spyglass as the Confederate leaders argued whether to attack the Union lines.

General Hood never said what he thought about the presence of this strange outsider, but he probably took it for granted. By that time, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur James Lyon Fremantle, H.M. Coldstream Guards, had become a familiar sight throughout the Confederacy.

He had arrived in Brownsville, Texas, three months earlier as a young man of twenty-eight on military leave from the British Army. He was traveling for pleasure, and, like the sailor who spends his shore leave rowing in the park, he naturally picked the only place where there was a war on. He had gone to the South instead of the North because he had the Victorians sympathy for the underdog (except where England was concerned), but he had no deep convictionshis real reason was adventure, pure and simple.

Fremantle threw himself enthusiastically into his trip, moving gradually from Brownsville across Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Georgia to the headquarters of General Braggs army in Tennessee. There he relaxed for a week and then moved on to Charleston, Richmond and finally joined General Lees army on its march to Gettysburg. As the echoes of the great battle died away, he suddenly discovered that his leave was almost up. Hurriedly he crossed the lines; satisfied the puzzled Federals that he might be peculiar but he was no spy; and took the next boat home, where he resumed an impeccable but uneventful career in the British colonial armies.

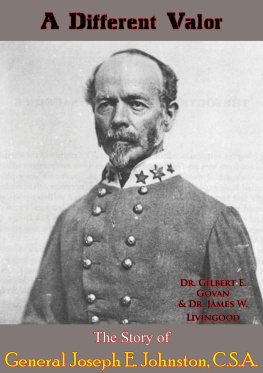

In the course of his whirlwind tour, Fremantle probably covered the South more thoroughly than anybody else who lived through the Confederacy. Certainly he saw more people. As he traveled along, he quickly showed that he was a marvelous celebrity collector. He looked up everyoneLee, Longstreet, Jeff Davis, Joe Johnston, Beauregard and all the rest. Remarkably enough, these meetings were rarely perfunctory. Fremantle charmed even the grumpiest Confederates, like Longstreet and Bragg. Invariably, he became a member of the familywhether he was sharing the only fork in Joe Johnstons mess or sharing Lees confidences at Gettysburg. So when Fremantle finally went home, he had not only been everywhere, but he knew everybody.

Like the good tourist he was, Fremantle kept a diary, recording the places he went, the sights he saw and the people he met. His unique experiences, and his wonderful knack for describing them, made the diary an entrancing account of the South at war. Before the end of 1863, it was published in London and in the following year was reprinted in New York and Mobile, Alabama. The Mobile edition came at a time when the South was growing desperate for supplies and appeared bound in flowered wallpaper.

Everywhere the diary stirred enormous interest. People bought it in England because pro-Southern feeling was running high; they bought it in the North because of the hungry curiosity about conditions in the Confederacy; they bought it in the South because any token of an Englishmans sympathy helped keep alive the desperate hope for foreign intervention. All these interests disappeared when the war ended. People wanted only to forget, and the diary was buried with the past.

Today, the national mood has changed. Sectional bitterness has given way to a common pride in the glory and courage of both sides. With this new perspective, Fremantles journal once again comes into its own. Nowhere is there a more revealing firsthand picture of the South at war. The sources of her strength and the seeds of her weakness parade by in a curiously contradictory pattern. We see disabled veterans given special work to stretch the last ounce of Southern manpowerwhile weak conscription and poor discipline simultaneously eat away the armies in the field. We see splendid resourcefulness in building from scratch an entire munitions industryand we find it closed on Sundays, even as late as Gettysburg.

Nor is Fremantle only concerned with important problems. Hes a master at painting in trivial details that bring the war and its personalities to lifeGeneral Magruder in a gay evening of amateur theatricals; General Bragg getting baptized; General Joe Johnston gathering wood for a locomotive; General Longstreet whittling on a stick at Gettysburg; General Beauregard getting gray hairs due not to lack of sleep but lack of hair tonic. Equally vivid are the pictures of unnamed and unsung heroesLees veterans in tattered butternut; saucy Pennsylvania girls taunting the Confederate invaders.

Today, the appeal of Fremantles journal extends far beyond the Civil War. It is one of the best contemporary accounts we have of American frontier life. Fremantle covers everythinghow to address a mule team effectively; how to get first to a water hole; how to dodge tobacco juice; how polecat tastes. We meet rangers so tough they scalp the Indiansyet so gentle they show nothing but kindness to women, strangers and the weak. We see a rip-roaring community, where the locomotive engineer shoots his passenger, and the steamboat passengers shoot each other; yet a community so shy and bashful that the passengers pull down the stagecoach blinds every time they lose their clothes in a robbery.

Even more fascinating is the vivid picture Fremantle gives of America in its adolescent years. In a sense, our national voice was changing. We were neither out of pioneer days nor into modern times. The old was incongruously mixed with the new, and the new with the old, often when least expected. Its a world where one day, communication is limited to prairie schooner; the next, theres an exchange of playful telegrams worthy of a college sophomore. One day, theres an endless variety of elaborate cocktails to drink; the next, theres nothing but filthy water from a lonely mudhole. Within a space of twenty-four hours, Fremantle is first forced to do his traveling by stagecoach, then has the luxury of a berth on a sleeping car.

Fremantles diary plays another important role. It gives us a splendid portrait of that great institution of the nineteenth century, the British tourist. Serenely oblivious to the uproar around him, yet always ready to try anything, Fremantle is a superb example of the Old Breed.

Sometimes he is almost a caricature. He dutifully records all toasts to the Queen. He refuses to go to a party without his evening clothes. He searches in vain for a good old-fashioned cavalry charge with drawn sabers. Hes dismayed by the inability of the Confederate infantry to form a hollow square. He proudly reports each occasion when he has succeeded in burying his instincts and has managed to shake hands with somebody. On trains, he is always happy to take a seat in the ladies car, until he discovers, to his indignation, that one is liable to be ousted by a female.