This book has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2015 by Michael Sturma

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-61251-861-9 (eBook)

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

Contents

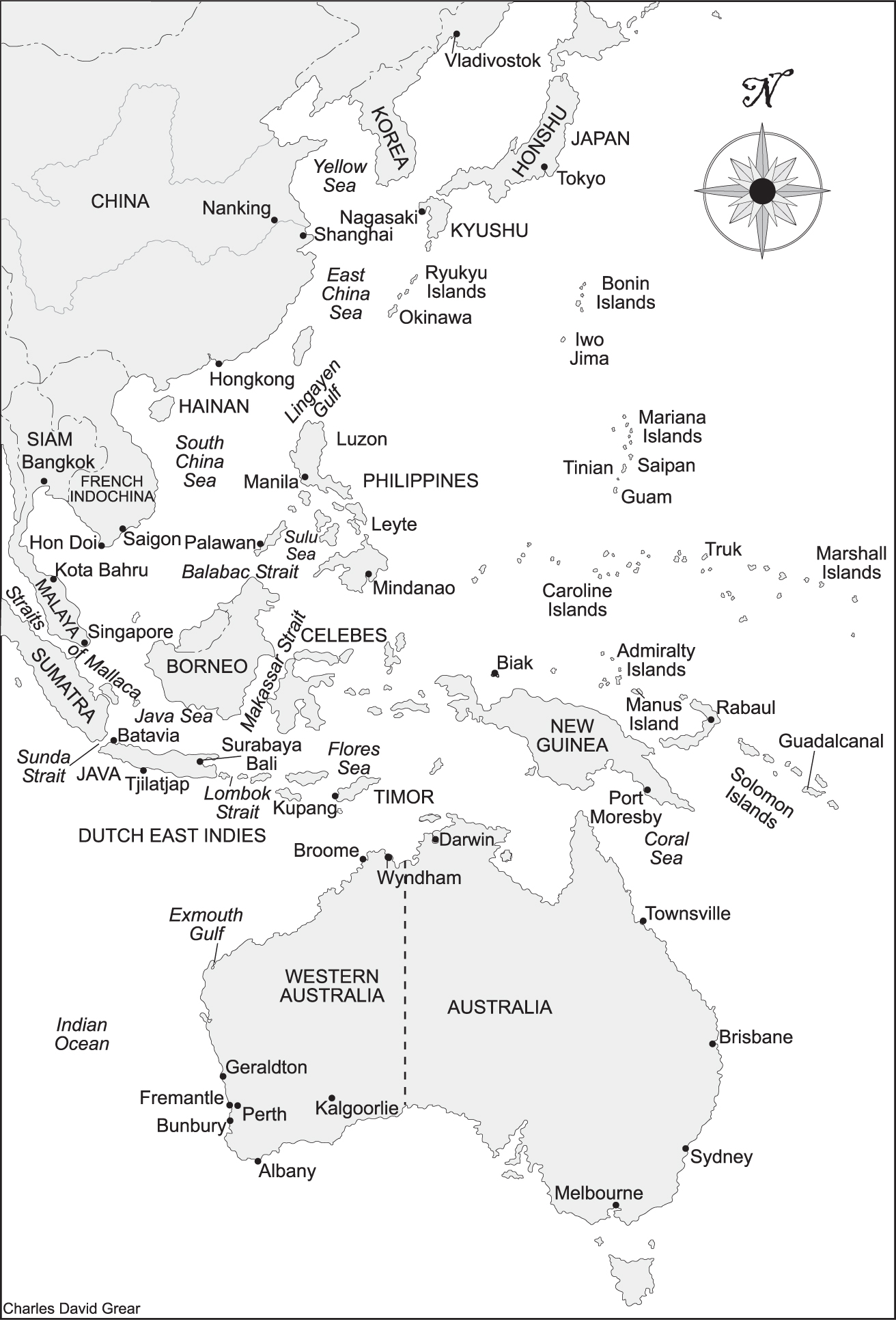

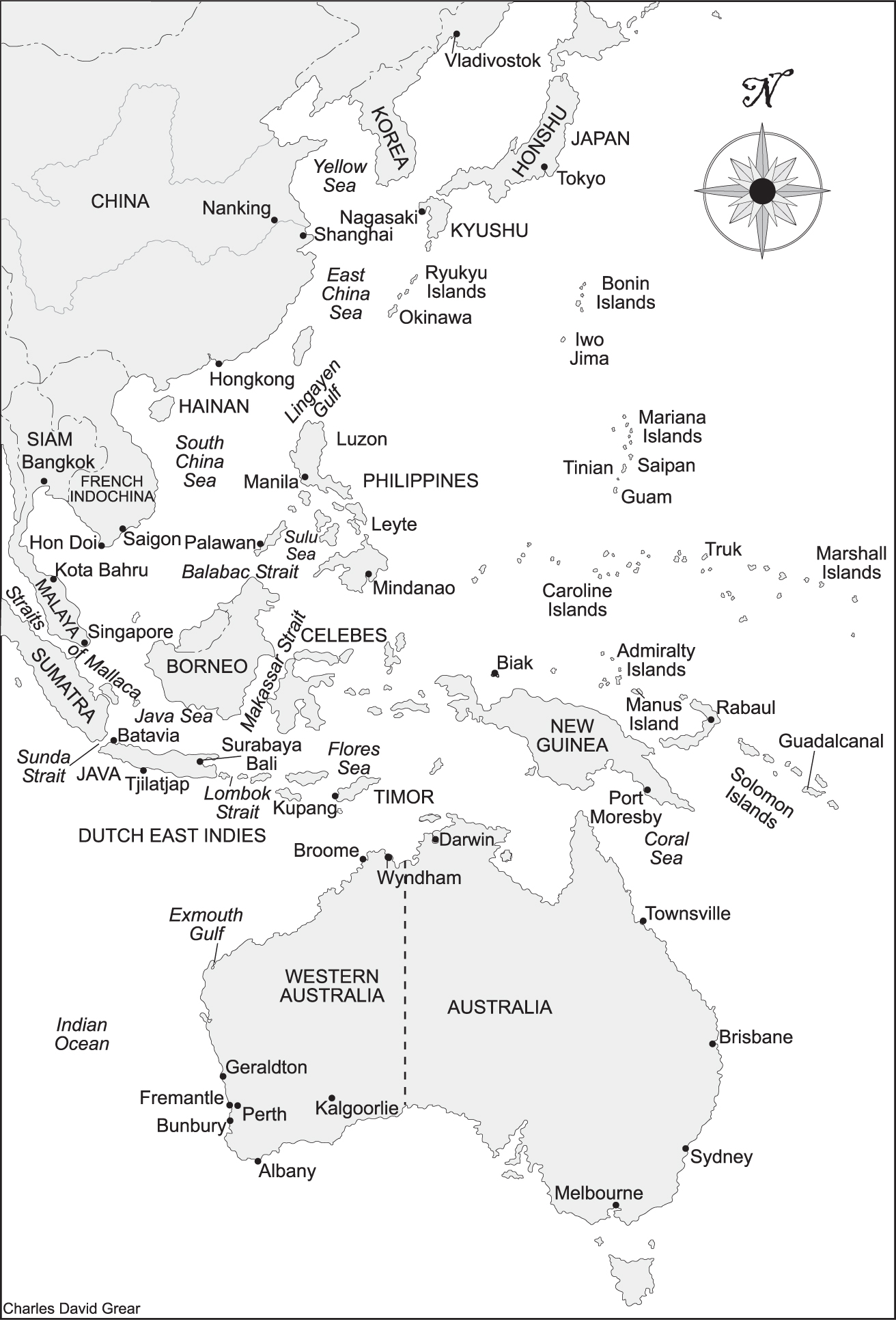

Map

Photos

Figure

And so you people of the land ere you lay your heads to dream,

Just pass a fleeting thought for the men who serve in a submarine.

A. B. Bristowe, A Visit to a Submarine

Over the years I have spared more than a fleeting thought for the men who served in submarines. In this endeavor I have accumulated a considerable debt, most of all to the submariners who have left oral histories and personal memoirs. I am also grateful for the assistance of numerous archivists and colleagues. Sally May, head of the Department of Maritime History, generously provided access to the recollections of Dutch, British, and American submariners held by the Western Australian Maritime Museum. Charles R. Hinman at the USS Bowfin Submarine Museum at Pearl Harbor has helped guide me through the museums resources over several visits. I thank George Malcolmson for his help in locating relevant material at the Royal Submarine Museum in Gosport, England. Thanks to Caitlin MacNeil for her assistance at the Victorian Archives Centre (Melbourne). Bob Price assisted by going through a selection of Boat Books held at the Submarine Force Museum in Groton, Connecticut. Craig McDonald generously shared information about some World War II submarine veterans from USS Puffer. Ernest Zeke Zellmer not only recorded his detailed memories as a submariner but put me in touch with some of his former crewmates from USS Cavalla. Thanks to Peter Nunan for sharing ephemera from the papers of Les Cottman.

At Murdoch University, Dr. Ian Chambers has afforded valuable technical and editorial assistance. Pam Mathews and Yolie Masnada have assisted in the ordering of research materials. As in the past, my longtime friend Professor Mike Durey provided a valued sounding board. My wife, Ying, is a continuous source of support. To all of these people my heartfelt gratitude.

T he submarine base at Fremantle, Western Australia, evolved from unpromising circumstances. Faced with the onslaught of the Japanese in World War II, U.S. submariners retreated to Fremantle as a port of last resort. While the American submarine base at Pearl Harbor was largely undamaged by the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, the base in the Philippines with the main contingent of U.S. submarines was devastated by an attack on December 10. A bomb sank USS Sealion as it underwent repairs at the Cavite Naval Yard, while the remaining twenty-eight American submarines stationed at Manila hurried out to sea in an attempt to both stem the Japanese invasion and avoid destruction.

With their base lost in the Philippines, the American submariners moved to the Netherlands East Indies, where for nearly two months Allied patrols were made from Surabaya and Tjilatjap on the island of Java. Soon, however, those bases too were overrun by the Japanese. Darwin, on the northern coast of Australia, was briefly considered as an alternative base, but, apart from the physical limitations of its harbor, any base there would be within striking distance of Japanese aircraft operating from recently captured islands to the north. From March 1942 on, Fremantle became Americas main submarine base in the Southwest Pacific through default. The port had the advantages of a good harbor and of being outside the range of land-based Japanese aircraft, but it also had disadvantages; it was far away from the areas where submarines carried out their patrols, and it was difficult to reinforce should the enemy launch a naval assault.

Despite the ports shortcomings, Fremantle became the most significant Allied submarine base in the Pacific after Pearl Harbor. During the war 127 American submarines made 353 war patrols from Fremantle, roughly a quarter of all U.S. patrols in the Pacific. Early in the war a small number of Dutch submarines were sent to Western Australia, and a total of ten Dutch boats made patrols from Fremantle. From August 1944 Royal Navy submarines established a substantial presence there, and thirty-one made patrols from Fremantle. Taken together, Fremantle

In relating the story of Fremantle submarines during the Second World War, three major themes emerge: courage, cooperation, and community. Submariners certainly had no monopoly on courage during the war, but as naval historian Malcolm Murfett observes, Even so, it is difficult not to see submariners as a special breed of seamen. Shared danger and shared responsibility for the groups survival was a key factor that contributed to the special status of submariners. Comradeship and loyalty to the group helps explain the willingness of men to face the hazards of submarine patrols again and again. Some of the most spectacular submarine patrols of the war were made from Fremantle under the command of such legends as Reuben Whitaker, Walt Griffith, and Sam Dealey. Allied submariners took enormous risks not only sinking enemy ships but conducting covert operations and rescuing beleaguered comrades from behind enemy lines. Eight U.S. submarines (Barbel, Bullhead, Flier, Grayling, Grenadier, Growler, Harder, and Robalo) were lost on patrols from Fremantle, remaining on eternal patrol, as the sailors phrased it. Another ten American submarines previously based at Fremantle (Bonefish, Grampus, Grayback, Gudgeon, Pickerel, S-39, Seawolf, Sculpin, Swordfish, and Trout) subsequently perished on patrols from other bases. The Dutch submarine O-19 was also lost on patrol from Western Australia, and HMS Porpoise, which carried out missions from Fremantle and was lost with all hands on a patrol from Trincomalee, became the last British submarine of the war lost to enemy action.

The courage of submariners may appear self-evident, but the degree of cooperation between allies is not always so clear. In an early effort at combined operations, the British general Sir Archibald Wavell was appointed head of the American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) command on January 15, 1942. The combined naval forces included a total of forty submarines: twenty-eight U.S., three British, and nine Dutch.Japanese Fifth Cruiser Squadron, on the other hand, had trained together for years.

Next page