Victoria Bruce - No Apparent Danger: The True Story of Volcanic Disaster at Galeras and Nevado Del Ruiz

Here you can read online Victoria Bruce - No Apparent Danger: The True Story of Volcanic Disaster at Galeras and Nevado Del Ruiz full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:No Apparent Danger: The True Story of Volcanic Disaster at Galeras and Nevado Del Ruiz

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

No Apparent Danger: The True Story of Volcanic Disaster at Galeras and Nevado Del Ruiz: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "No Apparent Danger: The True Story of Volcanic Disaster at Galeras and Nevado Del Ruiz" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

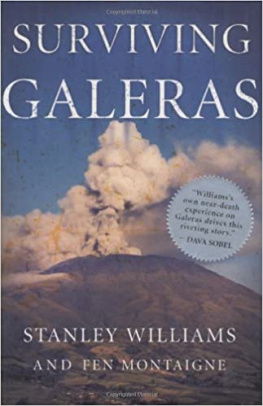

On January 14, 1993, a team of scientists descended into the crater of Galeras, a restless Andean volcano in southern Colombia, for a day of field research. As the group slowly moved across the rocky moonscape of the caldera near the heart of the volcano, Galeras erupted, its crater exploding in a barrage of burning rocks and glowing shrapnel. Nine men died instantly, their bodies torn apart by the blast.

While others watched helplessly from the rim, Colombian geologist Marta Calvache raced into the rumbling crater, praying to find survivors. This was Calvaches second volcanic disaster in less than a decade. In 1985, Calvache was part of a group of Colombias brightest young scientists that had been studying activity at Nevado del Ruiz, a volcano three hundred miles north of Galeras. They had warned of the dire consequences of an eruption for months, but their fledgling coalition lacked the resources and muscle to implement a plan of action or sway public opinion. When Nevado del Ruiz erupted suddenly in November 1985, it wiped the city of Armero off the face of the earth and killed more than twenty-three thousand peopleone of the worst natural disasters of the twentieth century.

No Apparent Danger links the characters and events of these two eruptions to tell a riveting story of scientific tragedy and human heroism. In the aftermath of Nevado del Ruiz, volcanologists from all over the world came to Galerassome to ensure that such horrors would never be repeated, some to conduct cutting-edge research, and some for personal gain. Seismologists, gas chemists, geologists, and geophysicists hoped to combine their separate areas of expertise to better understand and predict the behavior of monumental forces at work deep within the earth.

And yet, despite such expertise, experience, and training, crucial data were ignored or overlooked, essential safety precautions were bypassed, and fifteen people descended into a death trap at Galeras. Incredibly, expedition leader Stanley Williams was one of five who survived, aided bravely by Marta Calvache and her colleagues. But nine others were not so lucky.

Expertly detailing the turbulent history of Colombia and the geology of its snow-peaked volcanoes, Victoria Bruce weaves together the stories of the heroes, victims, survivors, and bystanders, evoking with great sensitivity what it means to live in the shadow of a volcano, a hairs-breadth away from unthinkable natural calamity, and shows how clashing cultures and scientific arrogance resulted in tragic and unnecessary loss of life.

Victoria Bruce: author's other books

Who wrote No Apparent Danger: The True Story of Volcanic Disaster at Galeras and Nevado Del Ruiz? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.