Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the Print Version

Also by Juliet PattersonThrenodyThe Truant Lover

SINKHOLE

A Legacy of Suicide

JULIET PATTERSON

MILKWEED EDITIONS

2022, Text by Juliet Patterson

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher: Milkweed Editions, 1011 Washington Avenue South, Suite 300, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55415. (800) 520-6455milkweed.org

Scripture taken from the New King James Version. Copyright 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Published 2022 by Milkweed Editions

Printed in Canada

Cover design by Mary Austin Speaker

22 23 24 25 26 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Patterson, Juliet, author.

Title: Sinkhole : a legacy of suicide / Juliet Patterson.

Description: First edition. | Minneapolis, Minnesota : Milkweed Editions, [2022] | Summary: A fractured reckoning with the legacy and inheritance of suicide in one American family--Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022001973 (print) | LCCN 2022001974 (ebook) | ISBN 9781571311764 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781571317476 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Suicide--United States.

Classification: LCC HV6548.U5 P38 2022 (print) | LCC HV6548. U5 (ebook) | DDC 362.280973--dc23/eng/20220421

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022001973

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022001974

Milkweed Editions is committed to ecological stewardship. We strive to align our book production practices with this principle, and to reduce the impact of our operations in the environment. We are a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit coalition of publishers, manufacturers, and authors working to protect the worlds endangered forests and conserve natural resources. Sinkhole was printed on acid-free 100% postconsumer-waste paper by Friesens Corporation.

Authors Note

This is partly a story of trying to understand suicide. This is also a story written through and about grief. In both cases, there are gaps to navigatein memory, in access, and in the historical recordand so this book should be considered a work of creative nonfiction, although I have done my best to ground this work in geographical and historical research and the stories of others, as well as my own experience as I lived it. Specifically, the three imagined final days of my relativesan attempt to understand the transient tempest in the mind, as psychologist Edwin S. Shneidman calls suicidewhile based in this research, do not represent actual transcriptions of thoughts or events.

Finally, I would like to note that this material may be difficult for some readers to encounter. If you or someone you know is in suicidal crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255).

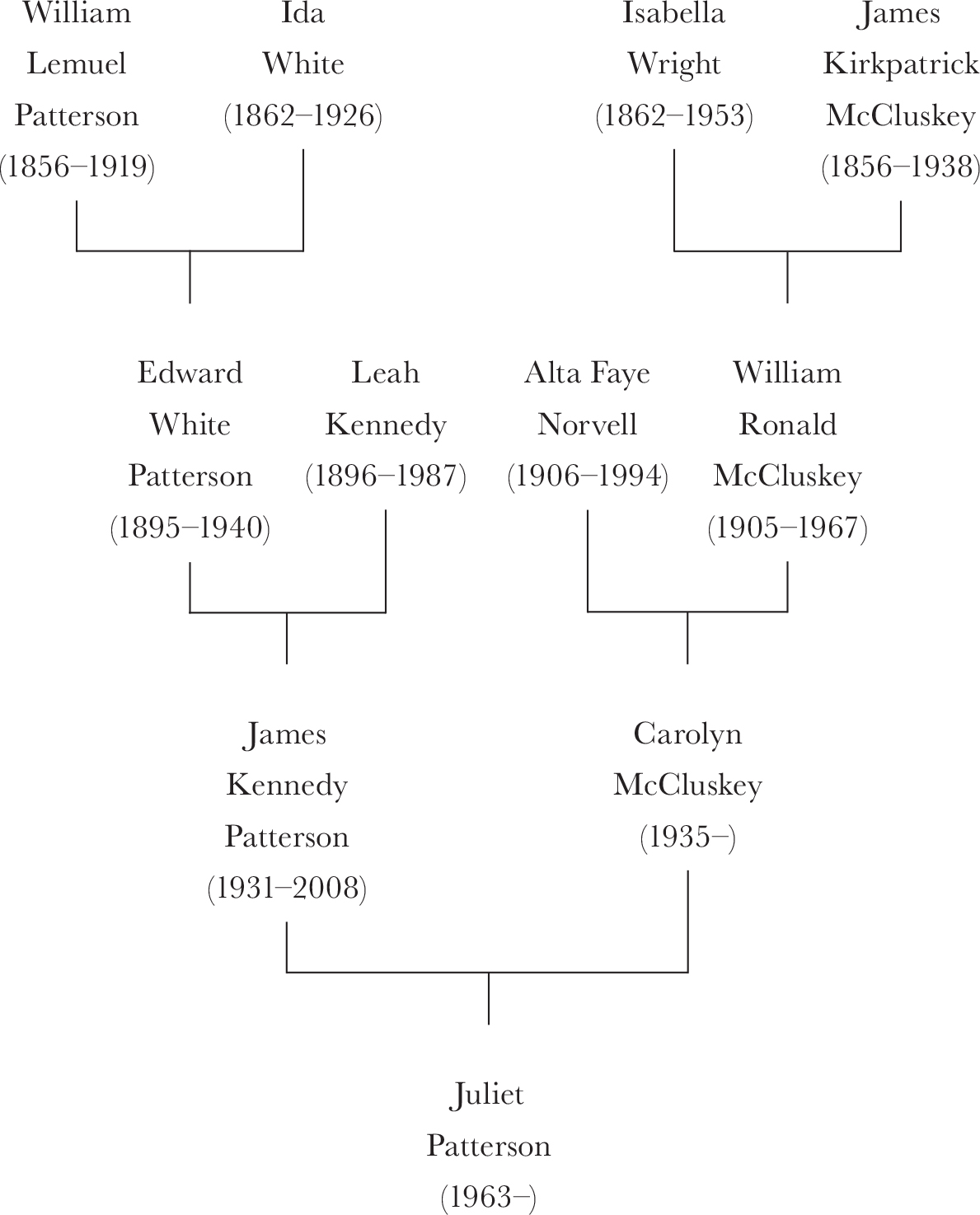

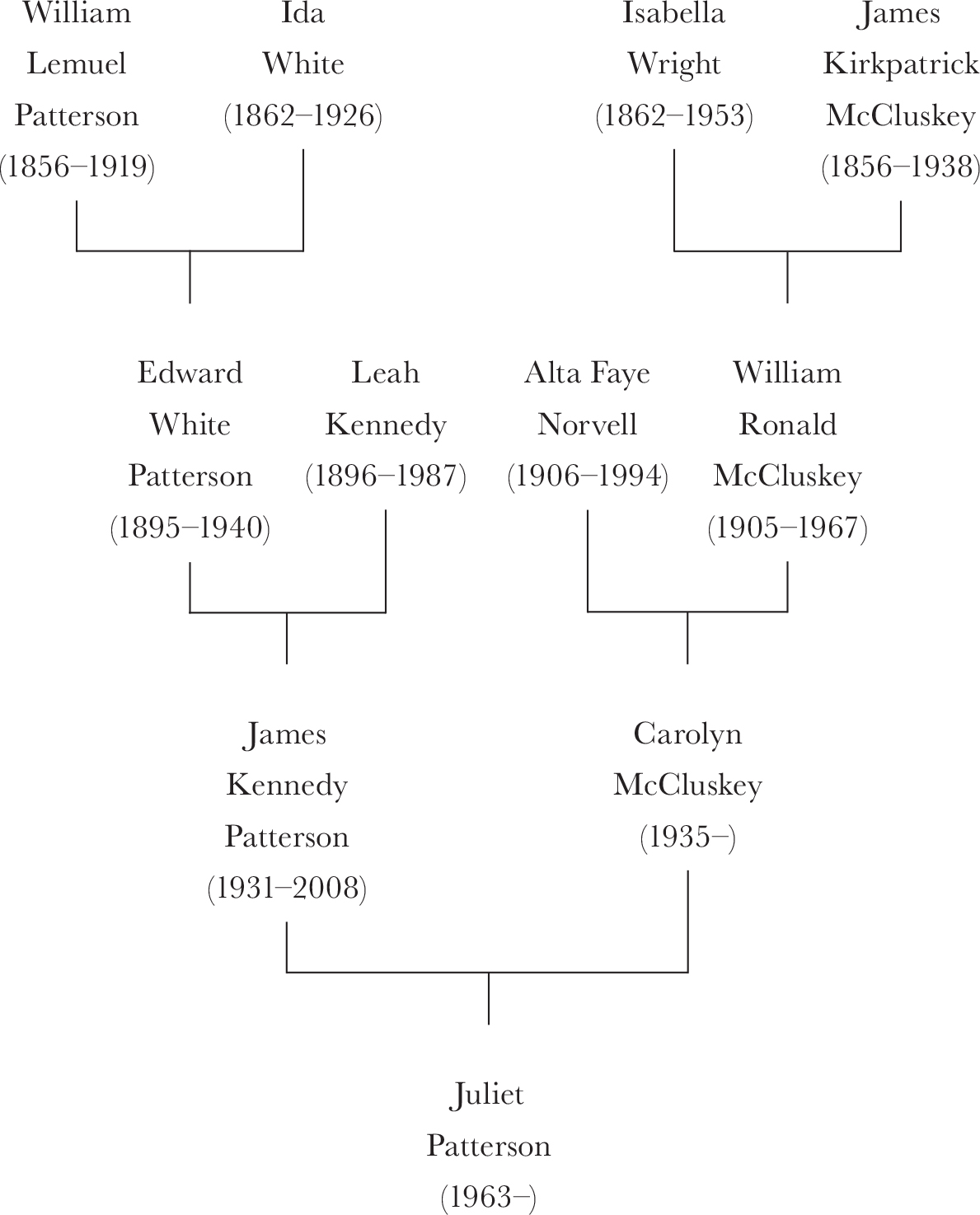

JULIET PATTERSONS FAMILY TREE

I am working out the vocabulary of my silence.

Muriel Rukeyser, The Speed of Darkness

And the end of all our exploringWill be to arrive where we startedAnd know the place for the first time.

T. S. Eliot, Little Gidding, Four Quartets

PART ONE

1.

Tuesday turns to Wednesday. December 17, 2008. The moon is almost in the last quarter. The sky is clear but pitch black. The temperature dips near zero, and already a foot of snow covers the ground in Minnesota. Coming home from work past midnight, my father swerves into the driveway somewhat carelessly, leaving his car pointed at an angle, a glove caught in the door. He enters the house through the garage door and descends into the basement, while my mother sleeps in the bedroom upstairs. He empties the contents of his pockets (keys, coins, cell phone) and removes everything from his money clip except his identification, which he leaves in his right rear pocket. He stands at the laundry utility sink and removes his dentures. He sits at his desk and writes a farewell note. He slips the note under the lid of the laptop computer on his desk and stacks several three-ring binders next to it.

He changes clothes. He pulls on a pair of long underwear and two sweaters, then an old winter coat, slightly torn at the sleeve. Before going out the door, he retrieves a small black sack that contains plastic bags, two box cutters, a pair of scissors, duct tape, cotton balls, and white nylon rope.

He walks outside, leaving the house through the garage, past the car in the driveway and into the street. He walks a block on Roy Street and turns left at Highland Parkway. He walks a half mile down a long sloping hill, near two water towers and a sprawling golf course buried in snow. He turns right and walks another mile, along the east side of the golf course and into a park. Just before he reaches Montreal Avenue, he enters a small parking lot adjacent to a playground and a bridge that extends over the road. Here the snow is deep, and it slows him as he walks to the bridges railing. From his sack, he takes one of the box cutters, the rope, and a plastic bag. Left inside is a note specifying his name and address. As he cuts the rope into two pieces, he accidentally nicks the thumb of his right hand. He makes two nooses. He ties the ropes to the railing and wraps the knots in duct tape. Then he climbs over the railing and stands on the concrete ledge, no more than a foot wide, overlooking a steep ravine. Below, to the left, a winding set of stairs is obscured by trees and snow. He pulls the plastic bag over his head and secures the nooses around his neck, tightening them just below his right ear. All of this takes only a matter of minutes.

My father chooses to die on the north end of the bridge. There, the canopy is so dense that, from the street, the structure appears to grow from the hill. In the dim light spreading from the railings, the crown of its arch bestows darkness.

When my father is found, nine inches of his right hand and wrist have frozen, though his trunk is still warm. The official time of death, 8:48 a.m., marks the moment when the police are dispatched to the scene, but the medical examiner estimates the actual time of death to be sometime between 2:00 and 3:00 a.m. My father hangs for nearly six hours through the night.

On the day my father died, a bitter cold wave swept across the northern regions of the countrysnow and sleet fell from the Twin Cities, where we lived, to states on the Eastern Seaboard. It was midwinter, near the solstice, a time marked by the shortening of days.

I woke that morning feeling drowsy and hopeless, largely a side effect of the Vicodin Id been given to relieve pain from injuries Id sustained in a car accident. One week earlier, my car had been rear-ended by a taxi in a bottleneck stretch of the I-94 freeway; the driver hadnt noticed that traffic ahead was slowing. Id seen him careening toward me in the rearview mirror and knew I was going to be hit. Though I was lucky not to suffer any fractures or injuries to my spine, I had strained the upper vertebra known as the axis and damaged ligaments in my neck, chest, and upper and lower back. No bruises or cuts, just invisible and severe soft-tissue damage. It was difficult to sit; to stand; to concentrate, reason, or think. Without hydrocodone, I could feel the torn edges of muscle and tendon, the path of nerve needlelike in my arms.