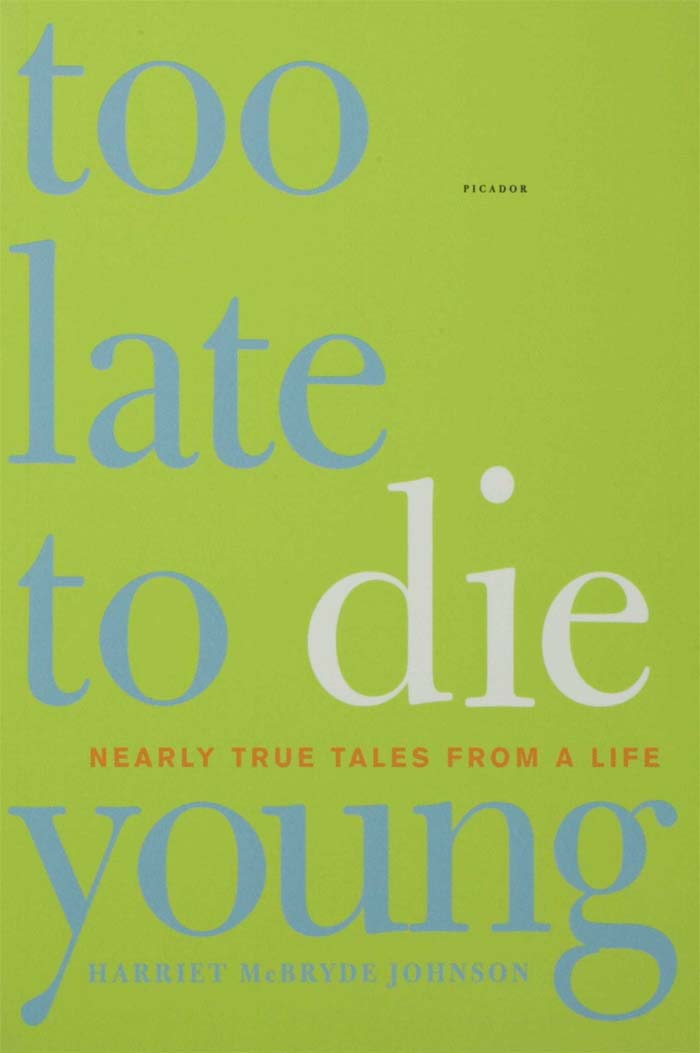

TOO LATE TO DIE YOUNG. Copyright 2005 by Harriet McBryde Johnson.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may

be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in

the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information,

address Picador, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.picadorusa.com

Picadoris a U.S. registered trademark and is used by Henry Holt and Company

under license from Pan Books Limited.

For information on Picador Reading Group Guides,

as well as ordering, please contact Picador.

Phone: 646-307-5629

Fax: 212-253-9627

E-mail: readinggroupguides@picadorusa.com

The chapter titled Unspeakable Conversations

appeared in slightly different form in The New

York Times Magazine on February 16, 2003.

Portions of chapters 1, 5, 6, and 7 have appeared

in slightly different form in New Mobility.

Designed by Victoria Hartman

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Johnson, Harriet McBryde.

Too late to die young / Harriet McBryde Johnson

p. cm.

ISBN 0-312-42571-6

EAN 978-0-312-42571-5

1. Johnson, Harriet McBride. 2. People with disabilities-United States Biography. I. Title.

HV3013.J65A3 2005

362.1967480092dc22

[B]

2004054007

First published in the United States by Henry Holt and Company

First Picador Edition: March 2006

D 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

Harriet McBryde Johnson has been a lawyer in Charleston, South Carolina, since 1985. Her solo practice emphasizes benefits and civil rights claims for poor and working people with disabilities. For more than twenty-five years, she has been active in the struggle for social justice, especially disability rights. She holds the world endurance record (fourteen years without interruption) for protesting the Jerry Lewis telethon for the Muscular Dystrophy Association. She served the City of Charleston Democratic Party for eleven years, first as secretary, and then as chair. She is a frequent contributor to The New York Times Magazine and to the disability press.

Too Late to Die Young

For all of those

who let their stories cross mine,

especially

my Valentine

Preface

I have come to expect it. The glassy smile. The concerned gaze. The double takesometimes hilariouswhen I roll out to meet a client in my waiting room or show up someplace where someone like me is not expected. The discombobulation that comes in my wake.

Its not that I am ugly. Its more that people dont know how to look at me. The power wheelchair is enough to inspire gawking, but thats the least of it. Much more impressive is the impact on my body of more than four decades of a muscle-wasting disease. Now, in my midforties, Im Karen Carpenterthin, flesh mostly vanished, a jumble of bones in a floppy bag of skin. When, in childhood, my muscles got too weak to hold up my spine, I tried a brace for a while, but fortunately a skittish anesthesiologist said no to fusion, plates, and pinsall the apparatus that might have kept me straight. At age fifteen, I threw away the back brace and let my spine reshape itself into a deep twisty S-curve. Now my right side is two deep canyons. To keep myself upright, I lean forward, rest my rib cage on my lap, plant my elbows on rolled towels beside my knees. Since my backbone found its own natural shape, Ive been entirely comfortable in my skin.

A few times in my lifeI recall particularly one largely crip, largely lesbian cookout in ColoradoIve been looked at as a rare kind of beauty. There is also the bizarre fact that in Charleston, South Carolina, where I live, some people call me Good Luck Lady: they consider it propitious to cross my path when a hurricane is coming and to kiss my head on voting day. But most often the reactions are decidedly negative. People on the street have been moved to comment:

I admire you for being out; most people would give up.

God bless you! Ill pray for you.

You dont let the pain hold you back, do you?

If I had to live like you, I think Id kill myself.

I used to try to explain that in fact I enjoy my life, that its a great sensual pleasure to zoom by power chair on these delicious muggy streets, that I have no more reason to kill myself than most people. But it gets tedious. God didnt put me on this street to provide disability awareness training to everyone who happens by. In fact, no god put anyone anywhere for any reason, if you want to know.

But most people dont want to know. They think they know everything there is to know just by looking at me. Thats how stereotypes work.

Because the world sets people with conspicuous disabilities apart as different, we become objects of fascination, curiosity, and analysis. We are read as avatars of misfortune and misery, stock figures in melodramas about courage and determination. The world wants our lives to fit into a few rigid narrative templates: how I conquered disability (and others can conquer their Bad Things!), how I adjusted to disability (and a positive attitude can move mountains!), how disability made me wise (you can only marvel and hope it never happens to you!), how disability brought me to Jesus (but redemption is waiting for you if only you pray).

For me, living a real life has meant resisting those formulaic narratives. Instead of letting the world turn me into a disability object, I have insisted on being a subject in the grammatical sense: not the passive me who is acted upon, but the active I who does things. I practice law and politics in Charleston, which Ill nominate as the most interesting small city in America. I travel. I find various odd adventures. I do my bit to help the disability rights movement change the world in fundamental ways.

And I tell stories. On one level, thats not unusual. Most Charleston peoplerich and poor, black and white, young and oldtell stories as part of daily life. For any Charleston lawyer, any Southern lawyer for that matter, storytelling skill comes so close to being a job requirement that maybe it should be tested on the bar exam. Beyond that, for me, storytelling is a survival tool, a means of getting people to do what I want. Im talking mainly about getting people to drive my van.

I dont drive, but work and politics frequently compel me to travel to Columbia. Its two hours each way on Interstate 26, a straight road through flat land, with many miles of pine trees, a few creeks, and one brown river. For Charleston people, its not a glamor destination. Were still angry that a coterie of real estate developers moved the state capital up there in the early nineteenth century. We all know there is no heat on earth worse than the inside of a van that has been baking in a Columbia parking lot all day.

For all these reasons, Charlestonians dont line up to drive to Columbia and back. To get a driver, I have to offer some incentive. Living on a budget with unpredictable cash flow, I naturally prefer not to pay when I can help it. Therefore, I offer stories.

My tales are true, or nearly true, as true as memory allows. They evolve in telling. They shift focus and emphasis, depending on what the listeneran active participant in the storys creationwants. There are questions, digressions, reactions. Easter lets me know when Ive found a characters voice by raising her right hand with an emphatic Thank you! With Dave, its silence that tells me the pacing is right; his habitual magpie-chatter stops. When Mike says, Wait a minute, let me get this straight, he leads me to an angle I hadnt noticed. I may recount the same sequence of events over and over again, but each listener makes a new story. Thats because storytelling itself is an activity, not an object. Stories are the closest we can come to shared experience.