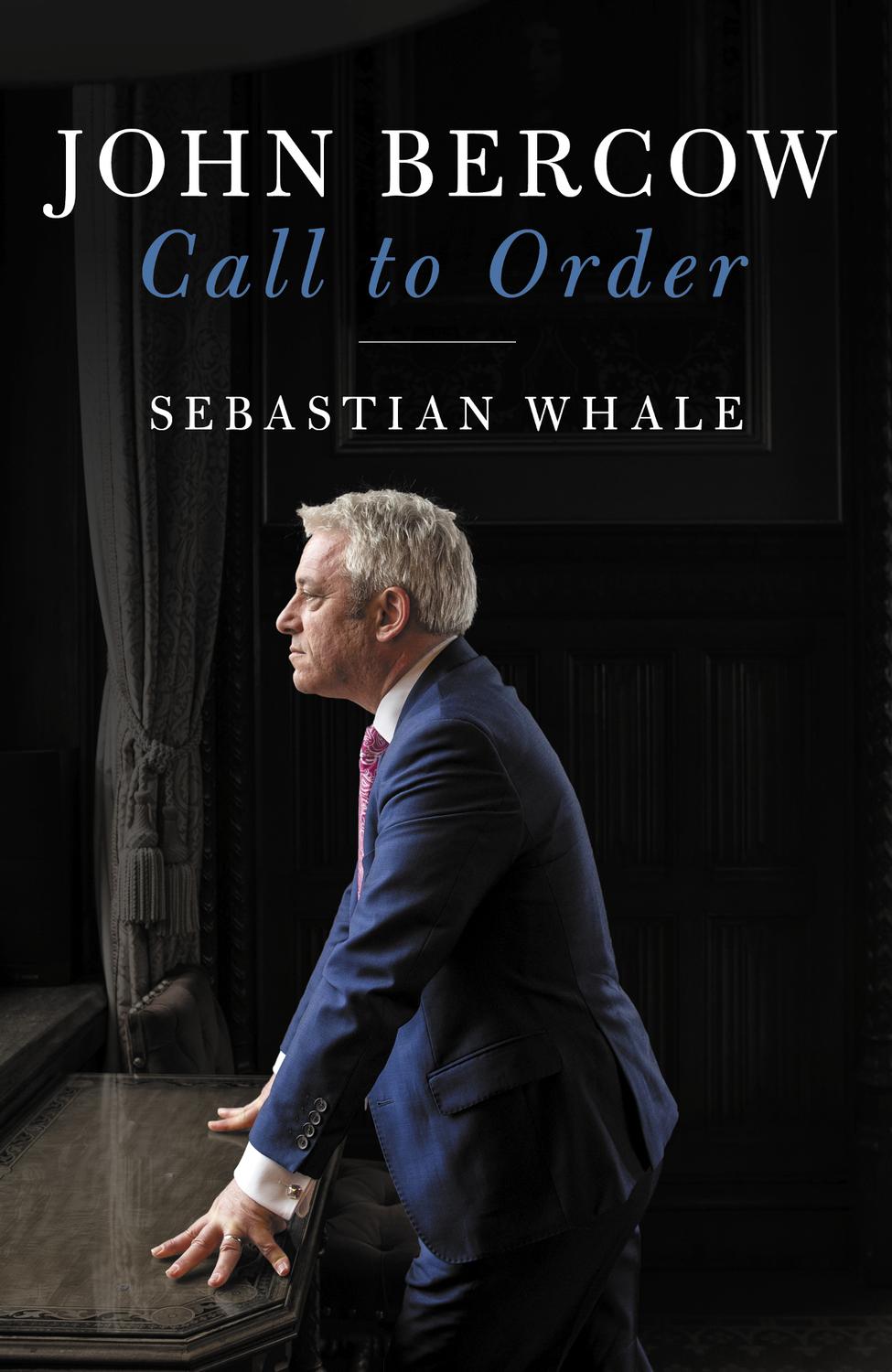

A t just after nine on 3 August 2019, my editor and good friend Daniel Bond sent me a message. Has Bercow had a biography? he asked. You should write it.

For reasons known only to himself, Dan was spending his Saturday night researching for a podcast with John Bercow (evidently, he was yet to stumble across Bobby Friedmans biography from 2011). Sitting at home in north-west London, I thought over his proposal. I would 100 per cent do that, I replied. Maybe I could look into it. Within two weeks, I had been commissioned.

If you think Brexit elicits controversy, try asking people for their views on John Bercow. The afternoon he announced his resignation, on 9 September 2019, I had consecutive interviews for this book with two Conservative MPs whose offices were just four doors apart. In the first meeting, the MP, a former minister, described Bercow as an extremist. The next MP, seconds down the corridor, told me Bercow was the great reforming Speaker.

Bercow has been not only one of the most eccentric characters in our national life but also one of the most contentious. In many ways, he was the Speaker for the times: divisive, polarising, abrasive. For better or worse, he was undoubtedly one of the most consequential.

While I had no preconceptions about his character before writing the book, I did have a few personal observations about Bercow. I found x some of his interventions self-indulgent, I thought there had been signs of bias particularly in his latter days but I was clear on this: his being in the chair created theatre. For the first time, the Speaker was often the story. He was another factor; an unknown quantity. For lovers of political drama, he was a star turn.

Bercow is not the first politician, nor will he be the last, to go on a journey. But his is one of the more notorious. Just how did a former member of the ultra-conservative Monday Club and secretary of its Immigration and Repatriation Committee become the darling of the liberal left? How could an ardent Eurosceptic, who would challenge his professors at the University of Essex over the UKs membership of the Common Market, end up not only voting Remain at an EU referendum but even helping to choreograph the resistance to a no-deal exit?

Such is his political voyage that many of Bercows former enemies on the left now count themselves as admirers. Take Linda Bellos, who remembers Bercow as being outrageous and appalling from their time together on Lambeth Council, and now regards him as a forthright man of honour. Conversely, his one-time comrades on the Conservative student right have scarcely a good word to say about him personally or professionally.

This remarkable transformation has been the source of much speculation. Plenty of people have wondered whether Bercows changing political outlook is primarily down to his wife, Sally, who also went on a notable journey from right to left. Others point out that his political beliefs often mirrored those that were in the ascendancy, such as Thatcherism in the 80s and centrism during New Labours heyday.

A word that crops up time and again about Bercow is mercurial. Im not sure youre ever seeing the real person, one of his contemporaries at the Federation of Conservative Students told me over lunch. Maybe Boris Johnson comes into this category. They develop layers on top of whoever they really are in order to cope with, or project themselves through, life.

For this book, I spoke to more than 140 people from across Bercows xi life. For many of his friends, the notion that he could bully someone is well beyond their comprehension. To them, Bercow is a thoughtful, humorous and kind man. For those who have incurred or witnessed Bercows wrath, they cannot fathom how other people are unable to see what to them is self-evident.

Many of those who have a deep hatred for Bercow a real, visceral hate had run-ins with him at some point during their careers. Over time, the resentment had grown strong and they were more than motivated to try to throw him under a bus. One Conservative MP had even hired an investigator to look into his dealings. Meanwhile, many opposition MPs wilfully buried their heads in the sand over some of the more concerning claims about Bercows behaviour in lieu of his progressive values. In other words, a selection of vengeful MPs would stop at nothing to bring him down; others were willing to back him come what may, sacrificing their principles on the altar of Brexit. In these muddied waters, Bercow was able to cling to a life-raft and survive for as long as he did.

Two months before publication, I had my rucksack stolen at Waterloo Station. Inside was my laptop and everything related to the book. I had most of it backed up and a kind man got in touch to say he had found a booklet on a road next to the station. I mention this because some people close to me asked if foul play had been at hand. I can categorically confirm that it was some chancer at Waterloo Station and had nothing to do with the former Speaker. But such is the air of conspiracy that surrounds Bercow that usually sensible people were indulging themselves in silly, unsubstantiated and left-field theories.

While writing, there were days when I found myself feeling sympathy for Bercow. His was a complicated and challenging childhood. During his early years in the Commons, he was subjected to some unacceptable abuse. Other days, as he stood up for backbenchers and revitalised the House of Commons as a place of scrutiny, I would be rooting for Bercow, cheering him on.

But there were other occasions when empathy would be replaced by xii anger. An anger based on his alleged treatment of others. An anger at those who protected him. An anger at those who appropriated causes to suit their political vendettas. An anger at peoples refusal to see him as anything other than their own projection of what they wanted him to be.

Bercow did not contribute to this book. Towards the end of the process, he was given the opportunity to comment on and fact-check certain anecdotes. Unless explicitly stated otherwise, the information comes from the research and interviews conducted over a period of five months. This book is my attempt at a balanced look at a complex man.

Not long after I was commissioned, it emerged that Bercow had written his own memoir. I believe my book offers different perspectives on the same story, shedding light on what was going on behind the scenes, and giving a voice to some of those who, for various reasons, have not been able to articulate their views. It must also be said that Bercows book did prompt some people, who otherwise had stayed silent, to reach out.

This is the story of John Simon Bercow, the son of a taxi driver from north London, and the 157th Speaker of the House of Commons.

F or this book I am indebted to a number of people. Dan, whose idea this was in the first place, and whose faith in me inspired me to go for it. Kevin, Georgina and Sally, who selflessly picked up the slack without any reservation while I was off work. John Johnston, who not only helped me stand up a couple of stories but also provided valuable advice throughout. Simon, Nitil, Adam and Mike, who gave me the all-clear to pursue my own project. Shivani, who helped with research early on. Andy, without whose close friendship and generosity I would not have been able to finish this book. Boo, who I leaned on more than I ever have, and who supported me, as she always does, right the way through. Nick and Sally, who backed me to the hilt. To the rest of my family and friends, particularly Lucy, Jeremy and Luke, whose positive encouragement was a source of great energy. And Olivia, whose patience and guidance helped me get over the line. Finally, I would like to thank every person who gave up their time in order to contribute to this book. Without you, there would be a series of blanks left unfilled.