FIRST THANKS GO to my cousin David Gourevitch, who introduced me to Andy Rosenzweig, and to Rosenzweig himself for telling me his story of the Frankie Koehler case and entrusting me to investigate it further. I give thanks also to the other men and women whose stories and voices make up this story, and I pay homage to the memory of Richie Glennon and Pete McGinn.

Many thanks to David Remnick for providing me with a home at The New Yorker , where portions of A Cold Case first appeared and where I am surrounded by colleagues who make work a pleasure. I am especially gratefulfor the enthusiastic dedication of my editor, Jeffrey Frank, for the good counsel of Henry Finder and Dorothy Wickenden, and for Bill Bufords steadfast generosity. Ben McGrath and Anne Stringfield in the fact-checking department, as well as Perri Dorset, Elizabeth Pearson-Griffiths, and Nicole LaPorte, all provided great help in this project.

Many thanks to Elisabeth Sifton, my editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and to my publisher, Roger Straus, for their spirited commitment to my work. Many thanks for the long-standing support of Ursula Doyle, my editor at Picador-U.K. in London. Many thanks to Sarah Chalfant, my anchor at The Wylie Agency, a wise reader and kind friend, to Andrew Wylie, and to Michael Siegel of Michael Siegel and Associates.

And many special thanks for the generous hospitality of the Corporation of Yaddo, where much of this book was written.

Finally, I thank my parents, Jacqueline and Victor Gourevitch, my brother, Marc, and his family, and my friends Vijay Balakrishnan, Elizabeth Rubin, Gilles Peress, and Joey Xanders, whose companionship sustained me on the trail of A Cold Case .

ON NOVEMBER 15, 1944, an Army deserter named Frank Gilbert Koehler was arrested for burglary in New York City. Frankie, as he liked to be called, had no criminal record. He had walked off his post at Fort Dix, New Jersey, after suffering unsustainable financial reversals in a crap game in the latrine, and when it was discovered that he was fifteen years old and had lied about his age to enlist, he was sent to childrens court, declared a juvenile delinquent, and returned to military control. Six monthslater, KoehlerAWOL again, and for goodshot and killed a sixteen-year-old boy in an abandoned building on West Twenty-fourth Street. The next day, he surrendered to a policeman on a street corner and was taken to a station house, where he confessed. In consideration of his extreme youth and lack of parental guidancehe had left home at thirteen, following the death of his father, a burglarthe district attorney reduced his charge from homicide to murder in the second degree. In court, Koehler pleaded guilty, and the judge sent him upstate to spend five years at the Elmira Reformatory. He was released on May 17, 1950, and remained a free man for nine months and twenty-six days until he was found by police, at four in the morning, hiding on the catwalk between the tracks of the Third Avenue elevated train line at Thirty-fourth Street, after robbing a nearby bar and grill at gunpoint. As he was led back to the station platform, Koehler called out to a man standing there in the predawn gloom as if waiting for a train, Arthur, save me, save me, tell them I was with you. So that man, too, was taken into custody. Koehler and he had indeed been together all night. Theyd met at a Times Square cinema where the poster said THRILL CRAZY, KILL CRAZY, and thepicture was Gun Crazy , a story of fugitive lovers on a crime spree hurtling to their doom.

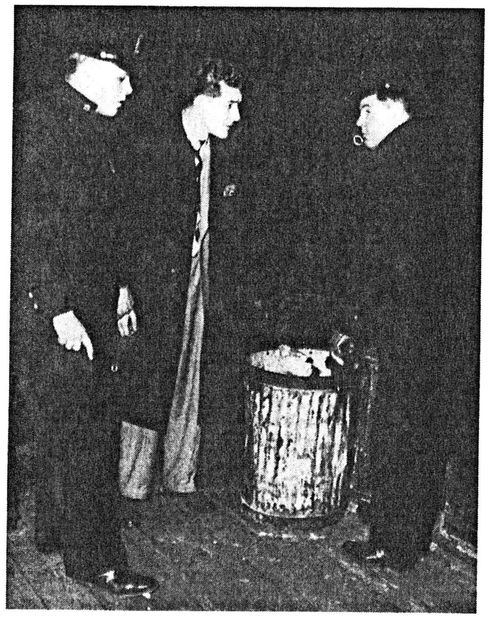

A news photograph of Koehler taken minutes after his arrest showed him to be a slight, dark-haired man, rather handsome and sharply dressed in an overcoat, business suit, white shirt, necktie, and handcuffs. When the picture appeared in the Daily Mirror , he was recognized by Carmella Basterrchea, the bookkeeper of a Murray Hill construction company, as one of two gunmen who had, a month earlier, stepped into her office late on a Friday afternoon, then, saying, All right, lady, this is a heist, and, Dont move or Ill plug you, made off with her payroll. Koehler admitted to both stickups, and once again he was sent upstate, this time to Green Haven Prison in Stormville, with a sentence of ten to twenty years. He served eleven and a half and was paroled in August 1962 at the age of thirty-three, having spent most of his life away.

Frank Koehler, under arrest for armed robbery, March 1951. Photograph from the Daily Mirror

Before the year was out, Frankie Koehler had a wife and legitimate employment in a machine shop. Later, he found union work as a stevedore on the West Side docks, then on the crew at the New York Coliseum on Columbus Circle, and he did not come to the attention of the police again until February 18, 1970. Around eight oclock on that evening, he was having drinks at Channel Seven, a restaurant on West Fifty-fourth Street, when he got into an argument with the owner, Pete McGinn, and a friend of McGinns named Richie Glennon. The issue was a womanthe wife of a mutual friend. Koehler had been having an affair with her while her husband was in prison, and she was now pregnant. McGinn declared that knocking up a jailed friends wife was about the lowest thing a lowlife could do, and Glennon seconded this judgment. Koehler came back with the opinion that they were a couple of scumbags themselves. So it went. Koehler spit in McGinns face, and the three men were soon out on the sidewalk, where Glennon watched as McGinn and Koehler had at each other and Koehler took a severe beating.

After that, McGinn went home, Glennon returned to the bar, and Koehler picked himself up off the pavement and went his own way for a while before returning to Channel Seven. Glennon was still there. Koehler had a drink with him and proposed that they sit down with McGinn to put their quarrel behind them in a gentlemanlyfashion. Glennon agreed, and phoned McGinn to say they were coming over to his place, which was a block north of Channel Seven, in what the next days News described as a luxury apartment building just up the street from Gov. Rockefellers New York office.

Richie Glennon and Pete McGinn had known each other from boyhood in the South Bronx, and both had found success in the restaurant business. McGinns Channel Seven was a popular watering hole for disc jockeys and anchormen from the nearby studios of ABC television and CBS radio, and Glennon owned a bistro on the Upper East Side called The Flower Pot, which was doing well enough for him to have taken the night off. Glennon had been having dinner at Channel Seven with his girlfriend, a nurse, and when he left with Frankie Koehler, she accompanied them. We went to McGinns apartment, and rode up in the elevator, she told me nearly thirty years later. It was the fourth floor. Richie told me to stay in the hall, and I waited out there till I heard these loud bangs. I thought they were fighting again, throwing things around. I heard the noiseI didnt even know they were shots, I just heard bangsand I opened the door. Frankie Koehler was running away with his smokinggun. I said, Wheres Richie? There was Richie on the floor.

Glennon lay on his back with his legs crossed comfortably at his ankles, his overcoat and suit jacket twisted beneath him, his left arm flung out, and the left side of his shirt bunched and soaked in blood from shoulder to waist around a small round hole over his rib cage. His girlfriend didnt notice that Pete McGinn was at the far end of the room, clad only in a bathrobe, with his right foot in a slipper and his left foot bare, lying facedown and dead in a puddle of blood on the parquet floor. I remember a big dog hopping around, she told me. It wasnt a small dog. It was a big dog. Beyond that, she was conscious only of Glennon. She didnt want to believe he was dead. She tried to pick him up and ask him where it hurt.