Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by E.R. Bills

All rights reserved

Cover image: Watercolor study known as A Human Skeleton. Rendered by English artist James Ward (October 23, 1769November 17, 1859) with graphite, brown ink and brown and gray wash. Image courtesy of Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.844.4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bills, E. R.

The 1910 Slocum Massacre : an act of genocide in East Texas / E.R. Bills.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-352-9

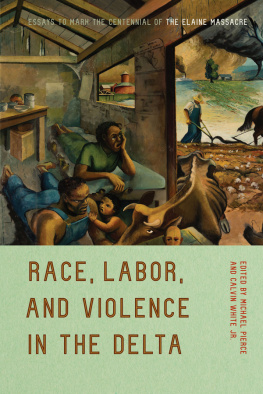

1. African Americans--Violence against--Texas--Slocum--History--20th century. 2. Slocum (Tex.)--Race relations--History--20th century. 3. Murder--Texas--Slocum--History--20th century. 4. Slocum (Tex.)--History--20th century. I. Title.

F394.S59B55 2014

976.4229--dc23

2014010148

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to my father, Eddie Ray Bills Sr.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Adopted by Resolution 260 (III) A of the United Nations General Assembly on December 9, 1948, ratified by the United States on November 25, 1988

The Slocum Massacre began on a Thursday or Friday in late July 1910, sometime after an African American was slow to address a promissory note. Or when a Houston County road supervisor asked a black man to round up help for road maintenance. Or the second an aging boxer referred to as the Great White Hope was dispatched in Reno, Nevada. Or when Anderson Countys vanquished, Confederate proud bitterly endured the policies of Reconstruction forty years prior.

Theories of origin abound, but the facts are clear.

White folks worked themselves into a panic and then a bloodlust. An untold number of black folks fled, disappeared and/or perished.

Some black folks retrieved and interred slaughtered loved ones while they hid or before they left. Some white folks slunk back to the scenes of bloody deeds and buried the evidence of their crimes by lantern light.

Many black folks abandoned the homes they had built and the land they owned and gave up the only lives they had ever known. Many white folks got away with murder.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to Felix Green, Warren Pettinos, Maxine Session, Leigh Cravin, Linda Sue Stuard and the volunteers of the Houston County Historical Commission.

CHAPTER 1

SLOCUM MASSACRE

I

Palestine was startled early this morning by a rural telephone message from Slocum bringing information that a race war was on in that part of the country, and saying that fifteen negroes were killed there last night and six others this morning.

Palestine Daily Herald, Afternoon Edition, July 30, 1910

On Friday, July 29, 1910, Anderson County sheriff William H. Black, of Palestine, received a trouble call at 11:00 p.m. It was John C. Lacy, sheriff of Houston County, immediately south of Anderson County.

Sheriff Lacy told Sheriff Black that a white man had killed two African Americans in Houston County, near the county line, and wondered if Black could meet him in Grapeland (in northern Houston County) to assist in the arrest. Some elements in both counties still hadnt come to terms with the idea that killing African Americans was against the law, so requesting backup in such cases was wise.

Sheriff Black informed Sheriff Lacy that he was busy, but he could break away if absolutely necessary. Sheriff Lacy told Sheriff Black not to worry about it and that he would attend to the matter himself.

At midnight, he called back.

During a preliminary investigation, Sheriff Lacy determined that the murders had occurred in Anderson County. Sheriff Black dispatched two deputy sheriffs forthwith.

The following morning, Sheriff Black traveled to southeastern Anderson County via horse-drawn carriage. He was thrown en route and significantly injured, but he continued on. When he arrived in the Slocum area, the local white community was in various stages of hysterics. Everybody seemed to be almost scared to death, Black later recalled. Everybody was armed with shotguns. They had the women and children all bunched up in places, and were guarding them. Many people were so scared and excited that they could hardly tell their own names.

In the days and weeks prior, a local African American businessman named Marsh Holley had gotten into a quarrel over a seventy-dollar promissory note with a handicapped white farmer named Reddin Alford. received word of Wilsons informal appointment, he was infuriated.

There was no evidence that Wilson ever actually approached Spurger, much less informed him his presence would be required on the county road repair crew; it was more a matter of southern white principle and racial hierarchy. The Confederacy was forty-five years departed, but broadly speaking, the Caucasian population of Texas did not consider African Americans their equals and went to great general, specific and systemic lengths to keep blacks second-class citizens in virtually every community (ergo black men did not tell white men it was time to help with county road maintenance).

When Spurger appeared at the site of the scheduled road improvements, he was carrying his shotgun. He later claimed he had brought it to go squirrel hunting on the way home. But instead of joining his fellow citizens in the road repair efforts, he flicked a dollar at the white county road overseer and said that he would not be working on county road details until a white man was appointed overseer. The white overseer no doubt regarded Spurger quizzically, and Wilson probably warily.

Spurger would later insist he received word that Wilson had muttered threateningly under his breath, but the claim was never substantiated.

Wilsons informal appointment to spread the word for the county road supervisor was clearly construed by Spurger as a violation of the white scheme of things in that part of the world, and once he took offense, he became a vociferous agitator. Holleys minor dispute with Alford grew major in association with Wilsons informal appointment, and Caucasian indignationstoked by Spurgerreinterpreted these events in predictable ways.

A black man tasked with informing his fellow citizens and neighbors that it was time to work on the county roads was suddenly a black overseer who was going to be in charge of white crews. A misunderstanding regarding a promissory note was now an uppity Negro trying to cheat a handicapped white man. Soon there were reports (all unsubstantiated) that African Americans in Anderson, Houston and Cherokee Counties were holding secret meetings and planning uprisings. Spurger and like-minded white folks even began claiming they had proof that a race riot was in the works.

Next page