Publication of this book was supported in part by a generous gift from Florence and James Peacock.

2019 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Merope Basic by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Slocum, Karla, 1963 author.

Title: Black towns, black futures : the enduring allure of a black place in the American West / Karla Slocum.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019011078 | ISBN 9781469653969 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469653976 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469653983 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansOklahomaHistory. | Cities and townsOklahomaHistory. | OklahomaHistory.

Classification: LCC E185.93.O4 S58 2019 | DDC 976.6/00496073dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019011078

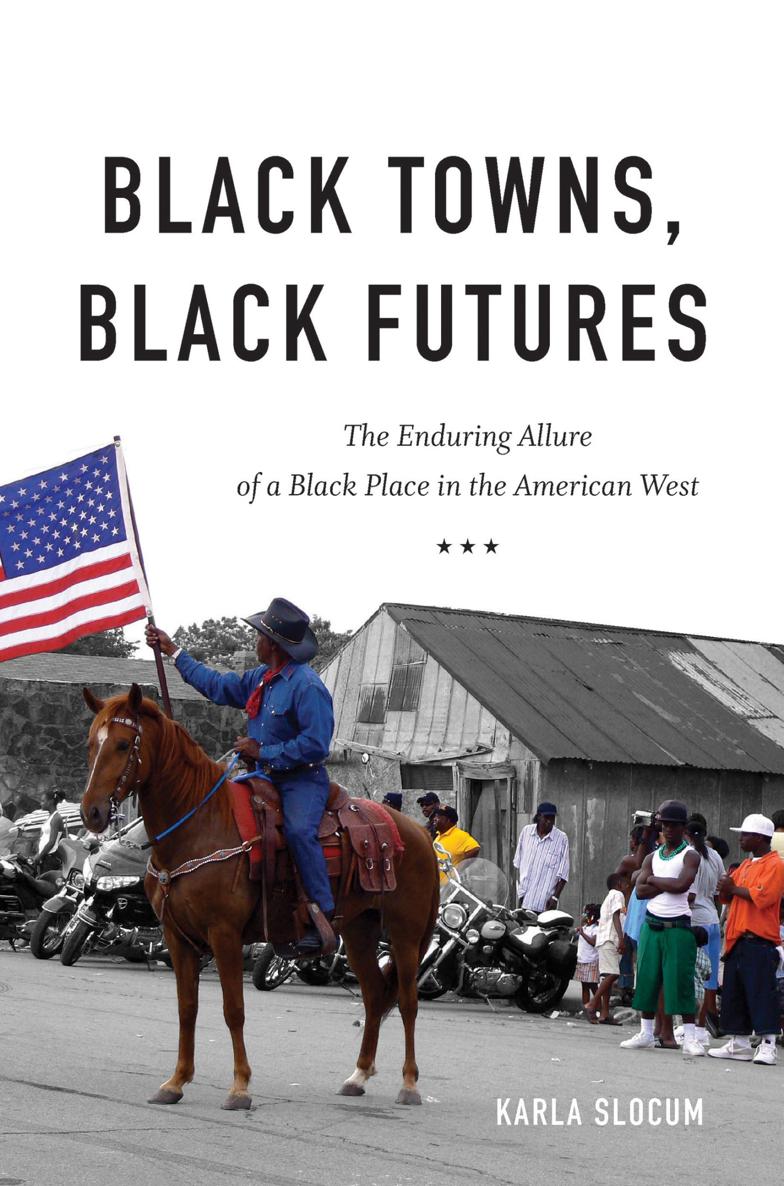

Cover illustration: Photo of U.S. flag by author.

Portions of chapter 2 were previously published in Black Towns and the Civil War: Touring Battles of Race, Nation, and Place, Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society 19, no. 1 (2017): 5974.

Preface

In 1969, my grandfather died at the age of fifty-eight from a contaminated blood transfusion. I was a young child at the time and barely knew him. However, posthumously, he is the force behind this book. Mozell C. Hill, my grandfather, spent more than seven years researching and writing about Oklahomas rural Black townsthe more than fifty post-Reconstructionera communities for people of African descentor what, in his day, were called All-Negro Societies. I only came to know this and so many other things about him twenty years after his passing when my grandmother succumbed to cancer. In the spring of 1989, my aunts, mother, sister, and I were cleaning out my grandmothers Harlem apartment and, while going through books on her balcony bookshelves, I came across texts by Black artists and scholars that had belonged to my grandfather. A just-starting-out graduate student, I was immediately taken with the extent of the collection. Although I knew that my grandfather taught at a university when he died, it was on that balcony that I gained a fuller sense of his intellectual life, the writers and thinkers who influenced him and the works that were important to him. It was also on that balcony that I first learned that my grandparents lived in a Black town, Langston, Oklahoma, the same town that he wrote about in his dissertation and where he worked at the states only historically Black university, Langston University. This discovery led me to start inquiring about my grandparents and mothers life in Oklahoma, and my mother became my primary source of information. Once I started asking questions, she was happy to share the stories.

There are the stories, for instance, of her childhood days in Langston. She recalled an outdoorsy and playful life full of days catching snakes with her preadolescent friends. She also boasted of her exceptional academic experience. The classes in her Black-town school were mixed ageprimary and secondary grades housed together in one school building, she recalled. She remained convinced that this was the reason she skipped two grades when the family moved to Chicago briefly in the late 1940s. I was exposed to things that kids in grades ahead of me were learning, she said.

Outside of Langston, she remembered life as less familiar, even uncomfortable. In Coyle, the White town neighboring Langston, she recalled an air of hostility toward Blacks and how her family never went there. Stay away from Coyle, she warned me, when I made my first trip to Oklahoma. She also described a trip that she took with her mother to Guthrie, once the capital of Oklahoma and about fifteen miles from Langston. In her recollection, this was the first time that she had left Langston, around the age of four. In a Guthrie store, she spotted a blonde White girl and, grabbing a lock of the girls hair, she said out loud to her mother, Mommy, whats this? She had never seen a White person before that trip, she told me as she was wrapping up the story.

Parts of my mothers stories resemble what elder residents in Black towns today will tell you about their childhood and community, past and present. They describe Black towns as bastions of freedom after encountering racism in the Jim Crow South. They recount experiencing community, comfort, easier living, and strength in Black towns. Outside the towns, they often describe danger, disorientation, and uneasein the past and sometimes even today.

In many ways, my grandfathers research reflects these same themes. In his dissertation, articles, and book, he argued that Black towns were utopian in their outlook, mostly socially egalitarian, and economically advanced, with many active Black businesses. In many ways, he described them as committed to being race communitiesthat is, communities organized around and proud of their Black identity as well as supportive of other Blacks. Black-town residents, he showed us, were committed to keeping distance from Whites due to their experiences and recollections of horrific oppression in the South.

My grandfather came to his conclusions about Black towns in part from his brother, who moved to the Oklahoma Black town of Boley in the early twentieth century. According to my mother, her uncle extolled the virtues of the place to the rest of his family still living in the South and Midwest. However, my grandfathers graduate education also shaped his thoughts about Black towns. As a doctoral student at the University of Chicago in the early 1940s, he became a proponent of the theory known as symbolic interactionism, the idea that interactions between different groups of people (in the case of his study, between Blacks and Whites) were meaning-filled, subjective encounters that influence groups identities and how they organize their individual communities.

My ideas about Black towns have been influenced by my training in cultural anthropology (a cousin of my grandfathers brand of sociology) and also by my research, which has involved engaging regularly with Black-town residents and their communities. However, as was the case for my grandfather, my family ties and newfound family stories play a role in how I think about the towns. My mothers memories as well as my research constructing who my grandfather was as a Black-town scholar, Black-town resident and employee, and the brother of a Black-town pioneer have also shaped how I have come to understand and think about the communities past and present. Like many new Black-town residents and visitors, I represent the kind of curious seeker for whom memory and personal history play a part in the motivation both to connect with Black towns and to understand what Black towns are. At this intersection of subjective experience and empirical research, I offer my study of the broad appeal of twenty-first-century Black towns for those of us who, through a variety of reasons, have become investors in Black towns stories and their possibilities.