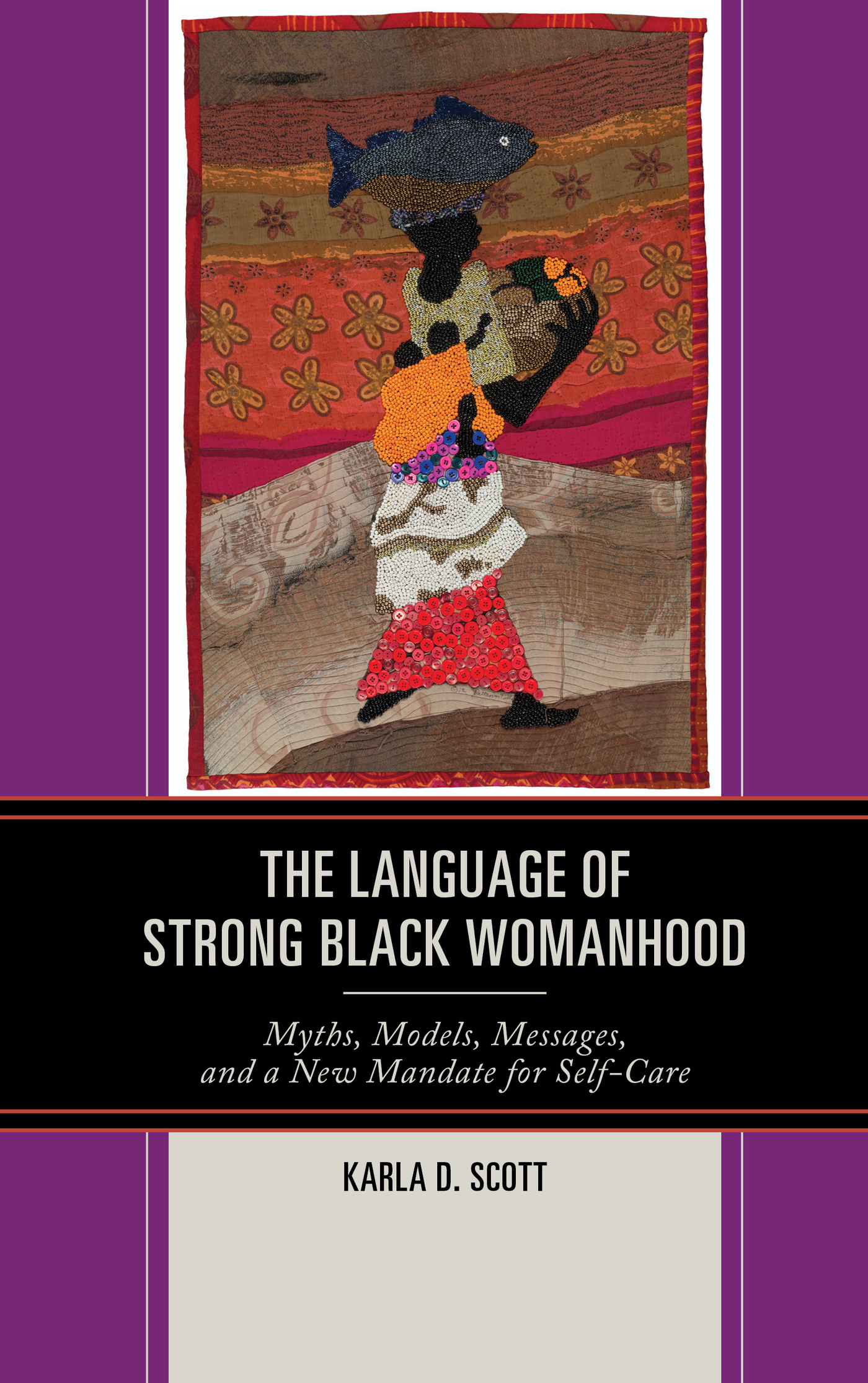

The Language of

Strong Black Womanhood

The Language of

Strong Black Womanhood

Myths, Models, Messages,

and a New Mandate for Self-Care

Karla D. Scott

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2017 by Lexington Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-4985-4408-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4985-4409-2 (electronic)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Dedicated with much love

to

my mother, Doris Jean Johnson Scott,

who modeled strength all her life

and

Patricia Ann Taylor

who introduced me to a new mandate for self-care.

I miss you both.

Acknowledgments

As a Black woman who often believes I must do everything alone to get it doneI now know that writing a book is not one such task. This book is the result of much support, love, and strength from many who joined me on this journey.

I am forever grateful, and remain in awe, of the Saint Louis University research assistants in the Department of Communication who worked magic at all points on the path. Many thanks to Ariana Martinez and Ivana Cvetkovic who encouraged me in the beginning with great company, conversation, and an endless supply of articles and books that got me movingand to Samir Adrissi who took me to the next level with tech skills that saved me from stalling out. I am so grateful I was able to learn so much from the three of you! Cindy Reed, your meticulous analysis and assistance affirmed this was indeed important work, and Kerry Wilson, thank you for sharing your copy editing skills.

Obviously there would be no study or book without the words and wisdom of the women who completed the online survey and participated in the focus groups. I thank you and am honored you chose to join me in an effort to give voice to the lived experiences of a group of Black women willing to share stories and struggles of strengthand work to make self-care a new mandate.

A special thank you to Dana Guyton for always keeping it real and sista support above and beyond... and to all you young, gifted, and Black women who found the African American Studies office and made it home, you motivate me to keep going. And deep appreciation to Dr. Brian Harasha who keeps my chi moving and energy flowing on my self-care journey.

My girls Charla Marie and CamiMaria know that you are always and forever my inspiration... and to my wonderful Wil thank you for support and strength that shows up when I need it mosteven if I dont admit it.

Introduction

The Making of a Myth: Strength to Survive

I identify as a strong Black woman, I relish in the fact that I come from a people who are still standing.

24-year-old survey participant

Several years ago Kerry, a second year graduate student, showed up at my office door one early afternoon with the look of a Black woman that says Im so tired but I gotta keep it all going. She smiled her usual Hey Doc and I heard the fatigue. It was midterms, that period of extreme overwhelm and Kerry was writing a thesis, applying to doctoral programs and mothering her energetic, artistic and intellectually curious tween daughter. Downtime for Kerry was a rare luxury.

She looked at me with steely sincerity and I got worried when she asked: If Black women are supposed to be able to handle anything, how do you know when it is too much?

She sighed, I shook my head and shrugged my shoulders as we shared the silenceI had no response; I was also in overwhelm. We strong Black women dont know what is too much to endure and are not sure when to ask for help or say no in order to practice care of self.

That moment with Kerry motivated my interest in a research project to examine how the mandate for strength endures in language, messages, and models that seem to be inherent in the lived experiences of strong Black women. If we are expected to be able to handle anything how is that learned, where do we hear it and see it as the model of Black womanhood? Why do we so easily embrace it and find it hard to say when it is too much in the name of self-care? The project explored those questions by giving voice to the lived experience of strength shared by Black women responding to an online survey and participating in focus groups. This book is the result of that study and creates an intentional space for those Black women to share their reality of what it is like to live with the mandate for strength in 21st-century contexts and explore how the mandate endures despite implications for the Black women who embrace it so readily in the name of self-survival and community support. It also questions the sustainability of the historical, mythical role of strong enough to handle anything in contemporary contexts and argues for the inclusion of self-care as critical for Black womens survival.

It is useful to begin this exploration with Chanequa Walker-Barnes compelling discussion of the three core features of Strong Black womanhoodcaregiving, independence, and emotional strength/regulation:

My use of the phrase, StrongBlackWoman, with the spaces omitted between the words, is intentional. The literary scrunching is meant to emphasize the distinction between being a Black woman who is strong and being a StrongBlackWoman. There are strong women (and men) in all racial and ethnic groups, individuals who possess a multiplicity of spiritual, emotional, and/or physical fortitudes that sustain them through periods of crisis and through journeys of struggle. This type of strength is not associated with any particular personality type, but instead exists as a component of varied and multilayered personalities, a component that may be invisible until a need for its manifestation arises. The StrongBlackWoman, in contrast, is a particular, and fixed way of being in the world. It is a racialized gender performance, a scripted role into which Black women are socialized, usually beginning in childhood. (2014, p. 34)

In this socialization it appears fortitude and struggle to handle anything are critical characteristics of Black womanhood, a role requiring an almost animalistic brute strength not often attributed to women of other races. Such a concept, also described as John Henrysim in Black women (Bronder, Speight, Witherspoon, and Thomas, 2014) has been examined with conflicting and contrasting findings. A construct developed to describe high effort coping and the belief that events can be negotiated via hard work and determination, John Henryism certainly provides a framework for seeing Black women as de mule of de world as Zora Neale Hurston described in Their Eyes Were Watching God

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.