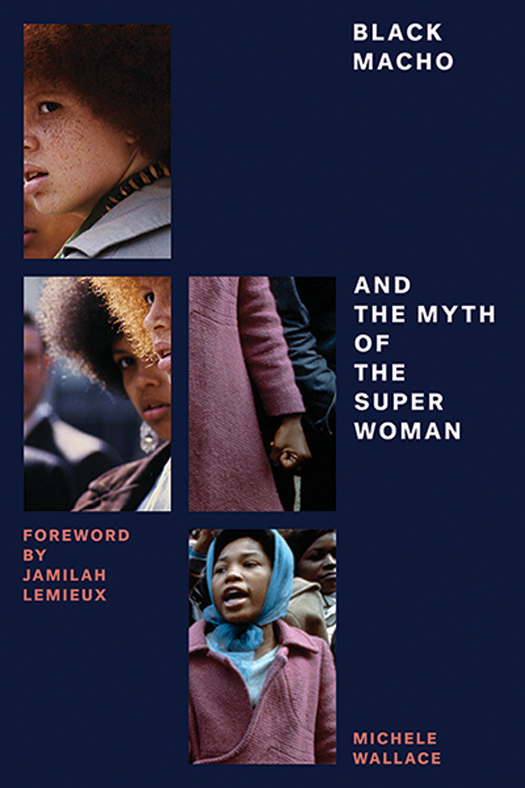

This edition published by Verso 2015

First Verso edition published 1990

First published by The Dial Press 1978

Vron Ware 1978, 1979, 1990, 1999, 2015

Foreword Jamilah Lemieux 2015

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-821-2 (PB)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-823-6 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-822-9 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

For my mother, Faith Ringgold

Contents

INTRODUCTION

How I Saw It Then, How I see It Now

PART I

Black Macho

PART II

The Myth of the Superwoman

FOREWORD

When I first picked up my mothers well-worn copy of Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman, Id already been calling myself a feminist for about two years and had penned a scathing takedown of a commercial for boxed macaroni and cheese that implied mothers were somehow responsible for bringing home the pasta and boiling it in a pot.

I was thirteen.

Despite the condition of the book implying that Mom had done what I would eventually docarry the book around in my purse until it literally fell apartI came to find out that she wasnt much of a fan of Michele Wallaces controversial debut. A member of SNCC, my mother was then fiercely protective of the image of the organization and its charismatic leader, Stokely Carmichael, who would come to be known as Kwame Tour. Furthermore, like many Black women of the Baby Boomer generation, she still struggled with the idea of publicly accusing Black men of sexismafter all, isnt the White Man our true and shared enemy? Dont we have enough problems without the in-fighting?

Wallace would rerelease the book in 1990 with a brutally honest, updated introductionHow I Saw It Then, How I See It Nowwhich I read some ten years later. In it, she took herself to the woodshed for what she considers to be misunderstandings on her part:

I now feel that the biggest failure of the book was that I didnt understand the problems inherent to nationalism as a liberationist strategy for women. I thought men were simply leaving women out because it hadnt really occurred to them to do otherwise I didnt see that it comes automatically to nationalist struggles to devalue the contributions of women.

She does, however, find space to defend herself:

My critique of the Black Power Movement was based upon a limited perception of it taken primarily from the mainstream media what I learned from this perspective was more important than many of my critics have been willing to allow.

Now in my early thirties, I better appreciate her ability to be self-critical and to recognize the flaws in Black Macho. However, I hope that both readers and Wallace alike see the importance of her bravery and the necessary roughness of this book. Wallace publicly walked the walk many Black feminist women do when the weight of recognizing Black patriarchy crashes squarely on our shoulders. She spoke pointedly of what scribe and scholar Moya Bailey has since labeled misogynoirsexism towards Black women; anti-Blackness that can come even from those who are Black, who were raised by Black women and profess to value Black people.

I also hope that this new edition is an opportunity for audiences who were of age at the time of the original publication and young people alike to truly grasp the significance of Black Macho. Darryl E. Pinckney, who reviewed the book for the Village Voice, where Wallace later served as a columnist, panned Wallaces work as autobiography, historical information, sociology, and mere opinion dressed up to resemble analysis.

Pinckney may not have been entirely wrong in his description, but what we know now, in the era of blogging, memoirs by twenty-five-year-olds and social media over-sharing, is that mere opinion can sometimes be as, if not more, valuable than analysis. Young Michele Wallaces theories and theses may not all hold weight when dissected by historians and scholars, or even pass her own standards at this point in her career, but her descriptions of what young feminist/womanist thinkers of my generation have come to know as Black girl pain were and are extremely important.

The criticisms leveled against the modern-day Black feminists with whom I am most readily associateda group of Gen X and millennial women and men who cut our literary teeth primarily on the internetare similar to those Black Macho faced. Though we have become more sophisticated and pointed in our language around our issues with Black men, the attempts at silencing us have remained sadly consistent with the sort of scathing, violent attempts made by writers like Robert Staples (The Black Scholar) against Wallace. Addressing sexism in anti-racist movements is divisive! To suggest that Black women face oppression at the hands of Black men distracts us from our true enemies: Racism! White supremacy! Isnt it fair to reason that Black women are somehow complicit in the plot to keep the Black man down, considering that Black girls allegedly fare better in classrooms and Black women outpace Black men in the workplace?

What has improved for the better, however, is that Black feminist thought has gone mainstream in ways that Wallace likely could not imagine when Black Macho was released and the backlash loud and immediate. When she sat with a makeup artist who didnt know what to do with brown skin, and a hairdresser who couldnt figure out how to make a natural look natural for a Ms. magazine cover that would help usher in much of the antiBlack Macho pushback, Wallace couldnt have imagined that one day feminist and scholar Melissa Harris-Perry would be the host of an eponymous MSNBC talk show that forces the corporate glam squad to understand Black skin and box braids every weekend. It would have been impossible to predict that technology would lead us to a place called social media, and the ability of Black women of all classes and creeds to debate feminist thought publicly and with authority would increase tenfold.

The world that received the first edition of Black Macho was very different than the one we know today, where Black feminists have demanded more than a seat at a proverbial table, but also a microphone. It would have been impossible to predict in 1979 that Beyonc, the biggest pop star in the world, would proudly stand in a shiny onesie in front of the word FEMINIST at the 2013 MTV Awards, only mere months after featuring a clip of author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie defining the word itself on her latest album (though the backlash from White feminists that followed wasnt exactly shocking).

Feminism is no longer a curse word in Black America. It may still be controversial, polarizing even. But it is increasingly visible, increasingly common. Search the word on Twitter and youll find hundreds, if not thousands, of often meaningful, nuanced conversations about what gender equity means to young Blacksyoull likely wade through some terribly offensive stuff to find those threads, but they exist and they are powerful.