Since the essays in this book span the work of my entire career as a writer and critic of culture, it would be impossible for me accurately to acknowledge every contributing factor. Nevertheless, I would like to mention a few special people who have either read and commented on my work or provided research assistance over the years. I would like to thank Jerome Rothenberg, Sherley Anne Williams and Michael Davidson in the Department of Literature at the University of California in San Diego for giving me my start as an academic. I would like to thank George Economou, R.C. Davis, Kathleen Welch, Ron Schleifer and David Gross in the Department of English at the University of Oklahoma. I would like to thank Isabel Marcus in the Law School, Carol Zemel in Art History, Michael Frisch in American Studies, Claire Kahane, Bill Warner, Neil Schmidt and William Fischer in the Department of English at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and James de Jongh, Leo Hammalian and Joshua Wilner in the Department of English at the City College of New York. I would like to extend a very special thank you to my friends and colleagues Brian Wallis, Maud Lavin, Phil Mariani, Susan McHenry, Coco Fusco, Margo Jefferson and E. Ann Kaplan.

My mother the artist Faith Ringgold has always been more than a mother. She has not only provided a constant source of inspiration in my work but she has also kindly granted us permission to reprint her story quilt Tar Beach (which is now in the collection of the Guggenheim Museum in New York) on the cover of the book. As for my husband, the actor Eugene Nesmith, he is quite indispensable to all my endeavors.

Also, I would like to thank Laurel Schreck, formerly at Verso, for having had the idea for the book. It has been a pleasure working with my editor Michael Sprinker and Colin Robinson, managing director of Verso.

I would also like to acknowledge the following previous appearances of the essays included in Invisibility Blues. Most of the revision is not really substantial and was meant to contribute to greater clarity, not to alter the main ideas. The one exception is chapter 23, Variations on Negation, which is substantially different from the previously published, much shorter version.

The material is here by kind permission of the following:

Memories of a 60s Girlhood: The Harlem I Love, The Village Voice, New York, 6 October 1975, pp. 267.

Anger in Isolation: A Black Feminists Search for Sisterhood, The Village Voice, New York, 28 July 1975, pp. 67.

Baby Faith, SAGE, Atlanta, Winter 1989, pp. 369; first published in Ms magazine, New York, July/August 1987, pp. 1546, 216, without Postscript.

For the Womens House, Feminist Art Journal, New York, April 1972.

A Womens Prison and The Movement, Womens World, New York, Summer 1972.

The Dah Principle: To Be Continued, Faith Ringgold: Twenty Years of Painting, Sculpture, Performance, The Studio Museum of Harlem, New York 1984.

Homelessness is Where the Heart Is, Zeta magazine, Boston, July/August 1988, pp. 4953.

Blues for Mr Spielberg, The Village Voice, New York, 18 March 1986, pp. 214, 26.

Michael Jackson, Black Modernisms and The Ecstasy of Communication, Global Television, eds Cynthia Schneider and Brian Wallis, Wedge Press & MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1989, pp. 30118.

Invisibility Blues Zeta magazine, Boston, June 1988, pp. 1721; and Grey Wolf Annual 5: Multicultural literacy, Grey Wolf Press, Saint Paul, Minn., 1988, pp. 16172.

Spike Lee and Black Women, The Nation, New York, 4 June 1988, pp. 8003.

Doing the Right Thing, Art Forum International, New York, October 1989, pp. 2022.

Entertainment Tomorrow, Zeta magazine, Boston, October 1988, pp. 515.

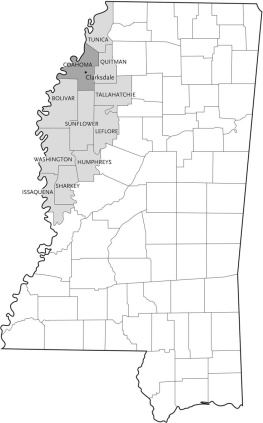

Invisibility Blues: Mississippi Burning and Bird, Art Forum International, April 1989, pp. 1112, here renamed Mississippi Burning and Bird.

For Colored Girls, the Rainbow is Not Enough, The Village Voice, New York, 16 August 1976, pp. 1089.

Slaves of History, The Womens Review of Books, Wellesley, Mass., October 1986, pp. 1, 34.

Ishmael Reeds Female Troubles, The Village Voice Literary Supplement, New York, December 1986, pp. 911.

Wilma Mankiller: Profile, Ms magazine, New York, January 1988, pp. 689.

Twenty Years Later, Zeta magazine, Boston, April 1988, pp. 2934.

Who Owns Zora Neale Hurston? Critics Carve Up the Legend, The Village Voice literary Supplement, New York, April 1988, pp. 1821.

Reading 1968: The Great American Whitewash, Zeta magazine and Dia Art Foundation: Discussions in Contemporary Culture, 4: Remaking History, eds Phil Mariani and Barbara Kruger, Bay Press, Seattle, 1989, pp. 97109.

Tim Rollins and KOS: The Amerilka Series, Amerika: Tim Rollins & KOS, ed. Gary Garrels, Dia Arts Foundation, New York, 1989, pp. 3748.

Variations on Negation and the Heresy of Black Feminist Creativity, Heresies, Fall 1989.

Negative Images: Towards a Black Feminist Cultural Criticism, forthcoming in Cultural Studies: Now and In The Future, eds Cary Nelson, Paula Treichler and Lawrence Grossberg, Routledge, New York, 1991.

The three illustrations are by Faith Ringgold: on

NEW INTRODUCTION

BY MICHELE WALLACE

Englewood, New Jersey 2007

When I first conceived of doing Invisibility Blues in 1990, the intention was to draw together all of the major writing I had done, beginning in my college years in 1969. Such a thing seemed to be particularly important to do after the success of my first book, Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman, and the controversy it had aroused. Of greatest concern to me was the notion that had been circulated that I was not actually a writer, a feminist, or an activist, or even serious about the topics brought up in that book. The point was, though, that I was serious and had not been put up to my deeds by white feminists of any description, as dear friend and colleague Ishmael Reed lovingly suggested in his book Reckless Eyeballing. (I addressed his suggestion in the Village Voice in 1984, and that essay appears here as Ishmael Reeds Female Trouble.) So, with