2020 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Designed by Jamison Cockerham

Set in Arno, Scala, and Egiziano

by codeMantra, Inc.

Cover photographs courtesy of Bradford Fair. Used with permission.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Foster, B. Brian, author.

Title: I dont like the blues : race, place, and the backbeat of black life / B. Brian Foster.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020018408 | ISBN 9781469660417 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469660424 (paperback) | ISBN 9781469660431 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Blues (Music)Social aspectsMississippi. | African AmericansMississippiSocial life and customs. | African AmericansMississippiSocial conditions.

Classification: LCC ML3918.B57 F67 2020 | DDC 781.64309762dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020018408

Prelude

I got it wrong from the beginning.

I think.

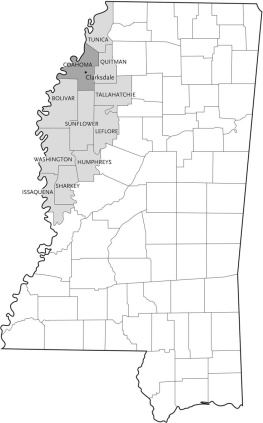

It wasnt that I had decided to move into the back bedroom, or that I had decided to move into the back bedroom of a house in the Mississippi Delta. It wasnt even that I had decided to move in the middle of the summer in the middle of the day. Well, I did get that part wrong; but Im thinking of another kind of wrong, one that happened in the middle of that night, my first night in Clarksdale: July 23, 2014.

That night, I wrote in my journal, I wonder if Ill be able to say something beautiful. The entry didnt have many words or much weight but for that, but when you are wrong it dont take much of either.

I got it wrong from the beginning.

I had gone to Clarksdale to study the South, to talk to enough people and spend enough time to say something worth knowing about the Black folks who called the region home. I had gone to set the record straight. To say how, for Black southerners, the civil rights movement was less a period and more a comma. That the 1960s was not when life stopped for Black folks but when it paused and reconfigured itself. Making the old sound new or at last seem different. I had gone to Clarksdale to say how the rural Black South had changed.

I was wrong, but not because it hadnt, just that I had only gone to say how it had.

I had gone to Mississippi from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), where I was working toward a PhD in sociology. I got there green and ambitious, ever reminded of what somebody had told me one time about UNC: it was a place that made blue-chip sociologists. Ever reminded of what somebody else had told me another time about blue-chip sociologists: they dont go anywhere to say. They go to show, then tell, which is another way to say describe, then explain. Describe the thing that happened. Describe the expression on her face. Describe what he did with his hands. Then explain what the thing meant. Explain how she felt. Explain how he explained what he did. The best blue-chip sociologists show, then tell. I got it wrong. I only wanted to tell, or as I wrote say something beautiful.

I wanted to say something beautiful, I wrote in an earlier version of this story.

I wrote that I wanted to write the thing that I had wanted and needed to read but could not find.

I wrote that I wanted to write about race and inequality in and from a place at the bottom of the margins.

I wrote.

I wanted to give a retrospective on a place long thought to be left behind. I wrote that I wanted to write something shiny and extravagant.

That was not the blues.

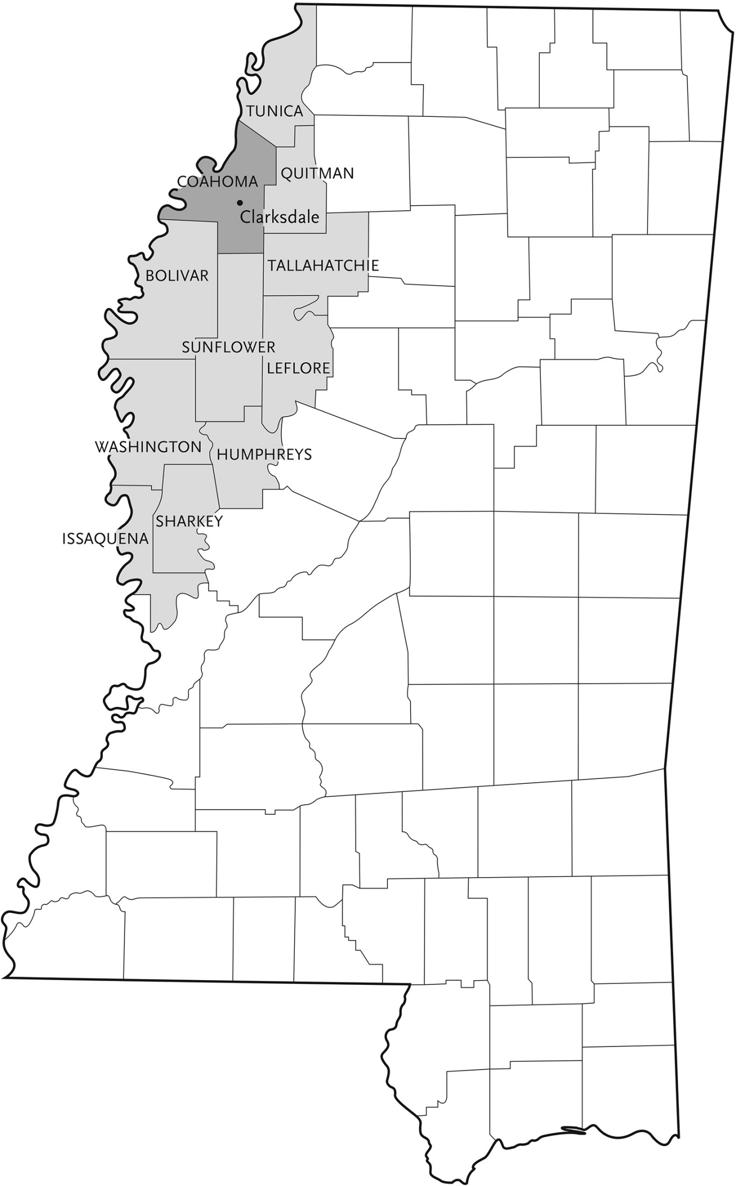

I had gone to Clarksdale, Mississippi, the land where the blues began, where Muddy Waters lived and Bessie Smith died, where the Crossroads lied (and folks lied on the Crossroads), where hundreds of people who played the blues played and hundreds of thousands of people who liked the blues watched; and I did not want to write the blues.

I did not like the blues. I wrote that too, for a time on just about everything that I could get my hands on. I am not studying the blues.

I did not want to be a blues scholar.

I did not want to be blue-chip.

I did not want B. B. King.

I did not like the blues.

So, I went looking for something else. Between that one middle-of-the-summer day in 2014 and another one in 2019, I lived, worked, and visited Clarksdale. I talked to hundreds of local folks. I went just about everywhere.

And, I found some things. In that same preface to that same earlier version of this story, I wrote I found what the Census and Clyde Woods had foretold: arrested development; limited opportunity; and big mansions with big yards in the distance. I saw in plain sight the persistence of the color line, which followed, ballast-by-ballast and mile-by-mile, the tracks of the Illinois Central Railroad, literally and figuratively splitting the town in two.

I wrote, I also found, as Zora once urged us to see, Black folks leading ordinary lives. In the summertime, people liked to be outside. Children laughed and played like children do, with boundless energy and wide smiles, jumping in and over ditches, riding bikes, waving sticks, throwing balls through all manner of hoops. Women and men worked long days, cursed and went to church, drank beer, smoked weed, and played dominos on all manner of tabletops. Folks washed and fixed on cars, sat and cursed on porches, sweated and laughed on the backs of pickup trucks with their shirts off. In the fall, they went to football games, then raucous basketball gyms in winter, a holiday parade at Christmas time, somebodys dinner table on Sundays. They lit candles, released balloons, and sang elegies for lost loved ones and neighbors. They fought, married, lived, died, and had birthday parties.

I wrote, I found more of the samethe expected and ordinaryamong the... people I met.... I heard stories of Civil Rights workers and Freedom Houses, Gangster Disciples and Vice Lords, guns, drugs, and dead bodies by the river. People talked about God and church, and reveled in their wildest dreams. They bemoaned politicians and sometimes other residents. They celebrated each other with laughter and flowers. Men bragged about sex and cars and their mommas. Women spoke of 100 days of peace. People sang to me, rapped their best freestyle verses to me, shared profoundly personal stories with me. They invited me into their homes, welcoming me with chicken and cheap liquor, shit talking, and more love and trust than I could have ever earned.