ACCLAIM FOR

Albert Murrays

The Hero and the Blues

The blues, Mr. Murray points out, are not raw black suffering but complex and sophisticated art. He is succinct, funny, and marvelously original in defining and describing what a hero is in fiction and dramahis reading of Oedipus is a knock-out, and his comparison of Manns Joseph to American black heroes is eye-opening. Everything he says is apposite to artists of every hue and derivation.

The New Yorker

ALSO BY Albert Murray

Good Morning Blues:

The Autobiography of Count Basie

(as told to Albert Murray)

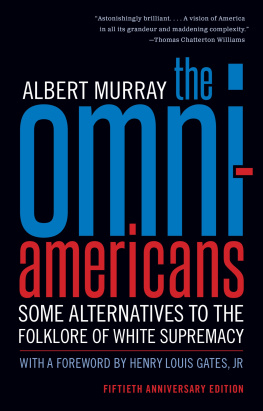

The Omni-Americans

South to a Very Old Place

Stomping the Blues

Train Whistle Guitar

The Spyglass Tree

The Seven League Boots

Albert Murray

The Hero and the Blues

Albert Murray was born in Nokomis, Alabama, in 1916. He grew up in Mobile and was educated at Tuskegee Institute, where he later taught literature and directed the college theater. A retired major in the U.S. Air Force, Murray has been OConnor Professor of Literature at Colgate University, visiting professor of literature at the University of Massachusetts in Boston, writer-in-residence at Emory University, and Paul Anthony Brick Lecturer at the University of Missouri. His other works include The Omni-Americans and The Hero and the Blues, collections of essays; South to a Very Old Place, an autobiography; Stomping the Blues, a history of the blues; Train Whistle Guitar and The Spyglass Tree, novels; and Good Morning Blues: The Autobiography of Count Basie (as told to Albert Murray). His most recent novel is The Seven League Boots. He lives in New York City.

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, JULY 1995

Copyright 1973 by Albert Murray

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by the University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri, in 1973.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Murray, Albert.

The hero and the blues/Albert Murray. 1st Vintage Books ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: [Columbia] : University of Missouri Press,

[1973], in series: The Paul Anthony Brick lectures.

eISBN: 978-0-307-82865-1

1 American literatureAfro-American authorsHistory and criticismTheory, etc. 2. Afro-AmericansSongs and music

History and criticism. 3. Blues (Music)History and criticism.

4. Heroes in literature. I. Title.

PS153.N5M87 1995

810.9896073dc20

94-45205

v3.1

Contents

THE SOCIAL FUNCTION

OF THE STORY TELLER

THE DYNAMICS OF

HEROIC ACTION

THE BLUES AND THE FABLE

IN THE FLESH

THE SOCIAL FUNCTION

OF THE STORY TELLER

Storybook images are as indispensable to the basic human processes of world comprehension and self definition (and hence personal motivation as well as purposeful group behavior) as are the formulas of physical science or the nomenclature of the social sciences. Such basic insights as may be derived from the makebelieve examples of literature are, moreover, as immediately applicable to the most urgent problems of everyday life as are scientific solutions.

With this premise, it might not be too much to say that the most delicately wrought short stories and the most elaborately textured novels, along with the most homespun anecdotes, parables, fables, tales, legends, and sagas, are as strongly motivated by immediate educational (which is to say moral and social) objectives as are the most elementary gestures, signs, labels, directives, and manuals of procedure. Indeed, at bottom perhaps even the most radical innovations in rhetoric and in narrative technique are best appreciated when viewed as efforts to refine the writers unique medium of instruction. In other words, to make the telling more effective is to make the tale more to the point, more meaningful, and in consequence, if not coincidentally, more useful. Nor is the painter or the musician any less concerned than the writer with achieving a telling effect.

Many contemporary American writers, editors, publishers, reviewers, and, alas, even teachersand accordingly an ever increasing proportion of the general American reading publicseem to have forgotten, however, that fiction of its very nature is most germane and useful not when it restricts itself to the tactical expediencies of social and political agitation and propaganda as such, but when it performs the fundamental and universal functions of literature as a fine art, regardless of its raw material or subject matter. Moreover, literary instruction, far from being indirect, is concomitant with artistic purpose as well as being multidimensional and comprehensive. As a matter of fact, fiction at its best may well be a more inclusive intellectual discipline than science or even philosophy. It can also function as an activating force which at times may be capable of even greater range and infinitely more evocative precision than music.

In truth, it is literature, in the primordial sense, which establishes the context for social and political action in the first place. The writer who creates stories or narrates incidents which embody the essential nature of human existence in his time not only describes the circumstances of human actuality and the emotional texture of personal experience, but also suggests commitments and endeavors which he assumes will contribute most to mans immediate welfare as well as to his ultimate fulfillment as a human being.

It is the writer as artist, not the social or political engineer or even the philosopher, who first comes to realize when the time is out of joint. It is he who determines the extent and gravity of the current human predicament, who in effect discovers and describes the hidden elements of destruction, sounds the alarm, and even (in the process of defining the villain) designates the targets. It is the storyteller working on his own terms as mythmaker (and by implication, as value maker), who defines the conflict, identifies the hero (which is to say the good manperhaps better, the adequate man), and decides the outcome; and in doing so he not only evokes the image of possibility, but also prefigures the contingencies of a happily balanced humanity and of the Great Good Place.

Thus no matter how sincere his intention, the writer does not automatically increase the social significance and usefulness of his fiction by subordinating his own legitimate esthetic preoccupations to those of the social and political technicians. If he so subserves, he only downgrades the responsibility which he alone has inherited. He discontinues or reduces the indispensable social and political service which art alone can provide, only to do something which many competent journalists (given a functional point of view or doctrineor a line of jive) can do as well and most good promoters can do better. Such an action on the part of a writer is every bit as regressive as that of, say, a surgeon who deserts the operating room to become a firstaid corpsman on the battlefield. It is as selfcontradictory as the act of an expert on policies and programming who, under the illusion of making himself more useful, resigns a key administrative position to become a subordinate who grinds out practical campaign slogans in the advertising department of the same organization. Or, worse still, isnt it indeed much the same as giving up a position on the coaching staff to become a cheerleader? What has he done except leave defining fundamentals in terms of his own sense of life only to represent somebody elses formulas?