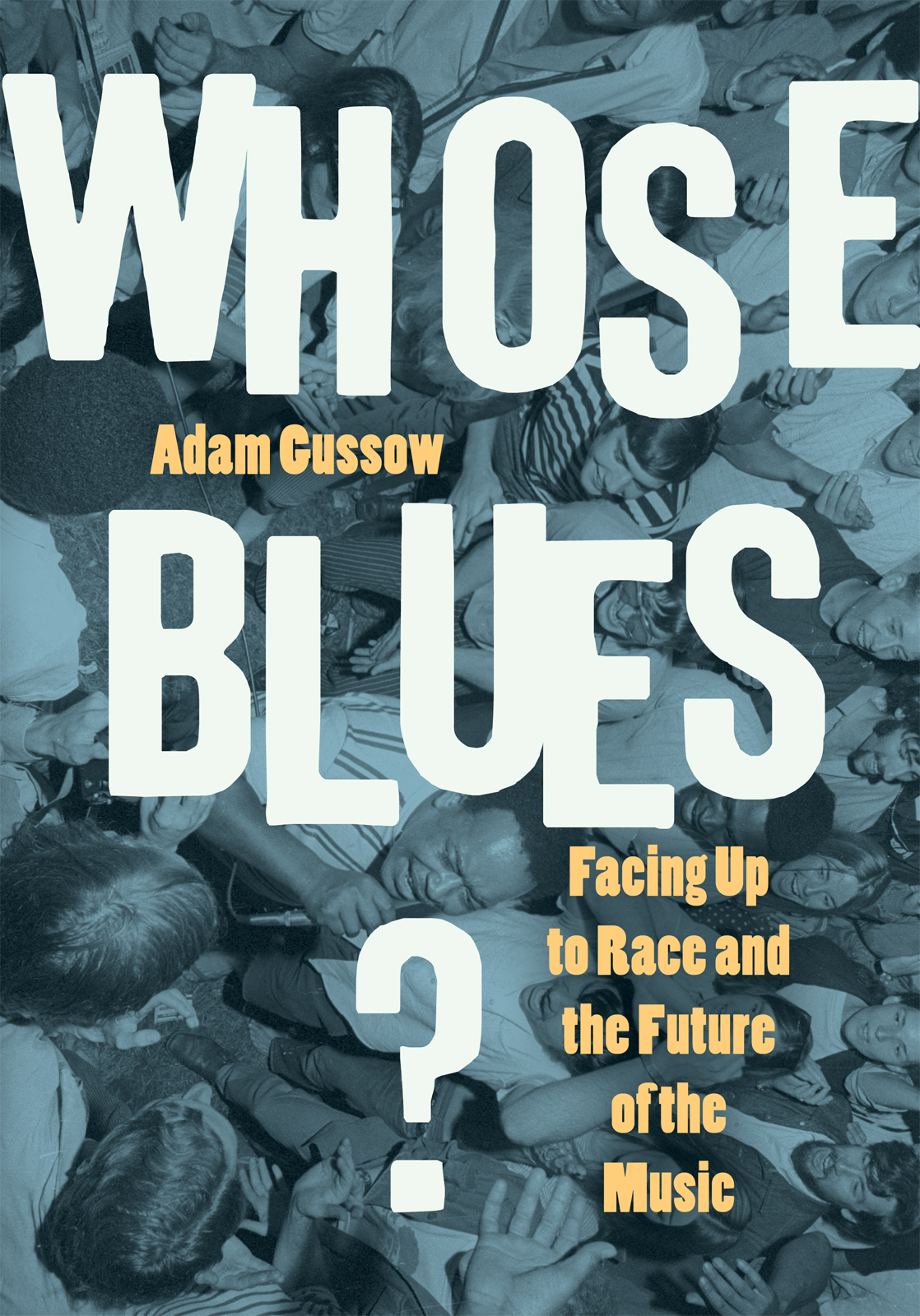

WHOSE BLUES?

Facing Up to Race and the Future of the Music

Adam Gussow

THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS

Chapel Hill

Publication of this book was supported in part by a generous gift from Cyndy and John OHara.

2020 Adam Gussow

All rights reserved

Designed by Jamison Cockerham

Set in Arno, Scala Sans, Poplar, Irby, and Saga by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Cover photograph: Tom Copi

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Gussow, Adam, author.

Title: Whose blues? : Facing up to race and the future of the music / Adam Gussow.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020015417 | ISBN 9781469660356 (cloth : alk.paper) | ISBN 9781469660363 (paperback : alk.paper) | ISBN 9781469660370 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Blues (Music)History and criticism. | Music and raceUnited States. | African AmericansUnited StatesMusicHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML3521 .G95 2020 | DDC 781.64309dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015417

Previous versions of ; Adam Gussow, W. C. Handy and the Birth of the Blues, Southern Cultures 24, no. 4 (2018): 4268; Adam Gussow, Fingering the Jagged Grain: Ellisons Wright and the Southern Blues Violences, boundary 2 30, no. 2 (2003): 13755; Adam Gussow, If Bessie Smith Had Killed Some White People: The Blues Revival and the Black Arts Movement, in New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement, ed. Margo Natalie Crawford and Lisa Gail Collins (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2006), 22752; and Adam Gussow, Giving It All Away: Race, Locale, and the Transformation of Blues Harmonica Education in the Digital Age, Journal of Popular Music Education 1, no. 2 (2017): 21532.

For

NAT RIDDLES

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

WHOSE BLUES?

bar 1

Introduction

Some people are born with a feeling for the blues, and it has nothing to do with color. I know black kids who love the blues and want to play it, but they have no feeling for it. Ive also heard white guys play the blues so deep it makes you want to cry.

Lonnie Brooks, Chicago blues musician (1990)

Its too bad that blacks are drifting away from the blues; its one of their greatest contributions to American culture. But lets face it: If it werent for whites, this music might be dead right now.

Howard Stovall, director, the Blues Foundation (1997)

These blues are not of you or for you, though some are about you. These blues are in spite of you, Mr. Charlie. These blues are mine and my childrens as they were my grandfathers and his fathers.

Sugar Blue, Chicago blues musician (2012)

Theres no essential race to a genre of music. Its a fabrication. Its been even painstakingly calculated. Which means that it doesnt belong inherently to anyone. So what if Im an Asian guy playing blues?

Dr. Ken Sugar Brown Kawashima, PhD, Chicago blues musician (2019)

THE BLUES WORLDthe contemporary American mainstream scene and its discussantshas a race problem. Its a problem with a long prehistory, one that first surged into view when the Black Arts Movement confronted the Blues Revival in the 1960s, then went dormant for several decades. The problem reemerged briefly in the mid-1990s, smoldered underground for a while, then burst into flames in Chicago between 2011 and 2012, the same time period in which an African American teenager, Trayvon Martin, was killed with one endlessly debated shot by George Zimmerman, a white Hispanic, in a Florida housing development. One goal of Whose Blues? is to address that problem, the blues-and-race problem, by staging an imaginative encounter between the two sides and then complicating the dialogue at every turn, so that a more thoughtful and productive conversation begins to emerge. (Blues literature is a help in this endeavor, which is why a secondary goal of this book is introducing fans of blues music to canonical works by W. C. Handy, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and other blues literary pioneers.)

Many decades ago, fresh out of college, I spent a few months working as a paralegal at a labor law firm in San Francisco. It was there that I first heard the term bad facts. Bad facts are facts that work against the case youre trying to make. They are part of what the court invokes as the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth when witnesses swear in: uncomfortable, incontrovertible realities that the other side will surely ride hard, and that your side wishes did not exist. But they do exist. Lucky for you, the other side also has its share of bad facts.

In Whose Blues? I do my best to highlight bad facts about the blues, the better to undercut a pair of ideologies that, considered individually, dont fully account for the music, the histories and experiential realities that lie behind it, the people who have made and continue to make it, and the lived worlds in which the music currently dwells. I term these ideologies black bluesism and blues universalism. Each ideology has a partial purchase on the truth. (The first ideology has a proportionally greater purchase on the truth, as this book will make clear.) Each comes with a ready-made slogan:

Blues is black music!

No black. No white. Just the blues.

The first slogan, a sentiment of long duration but uncertain provenance, became a battle cry in May 2015 as the title of a new blog by Corey Harris, a Colorado-born African American blues artist and MacArthur Fellowship winner of aggressively pan-Africanist leanings. Harris precipitated an uproar among white blues aficionados and musicians with an inaugural post titled Can White People Play the Blues?

Corey Harris

(courtesy of the John D. and Catharine T. MacArthur Foundation)

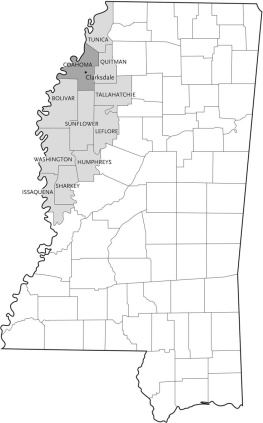

The second slogan, a familiar T-shirt meme on Beale Street in Memphis in the mid-1990s, was picked up and repurposed by Rick Looser, an advertising executive born in Alabama and based in Jackson, Mississippia southern white man, yeswho in 2005 decided to spend $300,000 of his own money on a campaign called Mississippi, Believe It. Hoping to upgrade the states racially retrograde image in the American imagination, Looser created a poster, headlined by the slogan and featuring photographs of B. B. King, Muddy Waters, and five other black male blues legends born in or associated with the state. Some see the world in black and white, begins the ad copy. Others see varying shades of gray. But, Mississippi taught the world to see and hear the Blues. It can still be found on many T-shirts.

Seductive as they are in this Facebook-shareable, meme-besotted age, slogans are a bad way to get at what TV commentator Van Jones calls the messy truth. But a conversation between slogans is something else. Whose Blues? strives to honor the passions, histories, and lived experience that inform both black bluesism and blues universalism, even while thinking critically about the way these ideologies enable their proponents to evade certain inconvenient truths. In this tribalist moment, I am seeking common ground for the blues tribe, my tribe.