Table of Contents

Without Johnny Parths inspiration, commitment, and dedication, several of my books on the blues and related fields would not have been possible, including this one, which draws on field recordings that he reissued on Document CDs. In recognition of my indebtedness to his work and profound appreciation of all the help he has given me over several decades, I have great pleasure in dedicating this book to Johnny Parth.

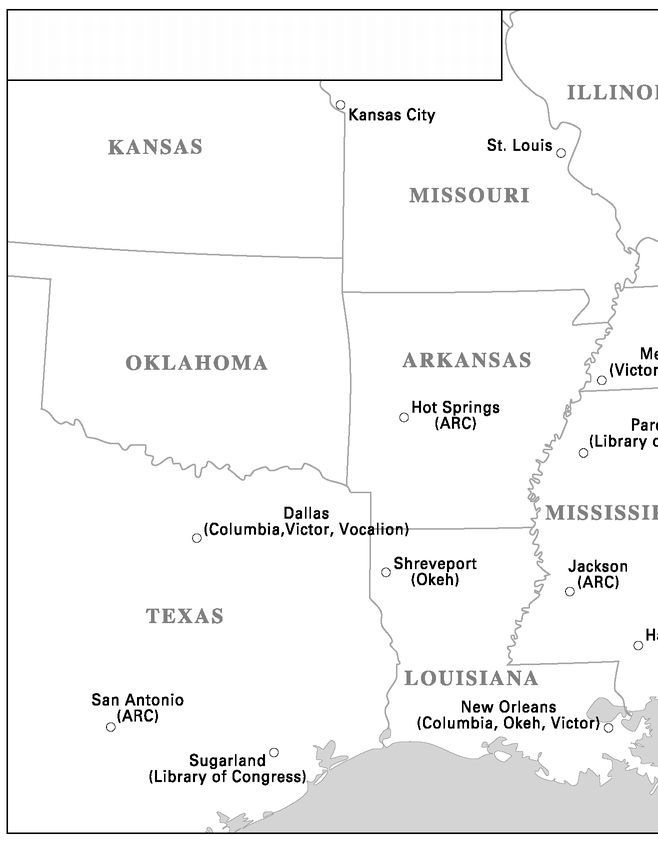

Major Field Locations Used by Commercial Recording Companies

INTRODUCTION

We must never forget the folk originals without which no such music would have been. So observed Alain Locke, writing in the mid-1930s of developments in jazz music, a major aspect of twentieth-century culture. The leading advocate of the Harlem Renaissance, Alain LeRoy Locke was interested in African American folk traditions, particularly spirituals and the subsequent emergence of blues music. In the Anthology of American Negro Literature, edited by V. F. Calverton in 1929, Locke had discussed the significance of African American cultural expression in American culture as a whole: Some of the most characteristic American things are Negro or Negroid, derivatives of the folk life of this darker tenth of the population, he observed, adding that it would become progressively the more so. Unfortunately, but temporarily, what is best known are the vulgarizations, he regretted, of which jazz and its by-products were in the ascendancy. We must not, cannot, disclaim the origin and quality of Jazz, he argued, since it was not a pure folk form, but a hybrid product of the reaction of the Negro folk song and dance upon popular and general elements of contemporary American life, being one-third folk idiom, one-third ordinary middle class American idea and sentiment, and one-third spirit of the machine-age.

For Professor Locke, the serious art which can best represent to the world the Negro of the present generation is contemporary Negro poetry. While tracing its origins, including the writings of Paul Laurence Dunbar and Vachel Lindsay, he quoted Charles S. Johnson, one of the principal figures of the Harlem Renaissance. Johnson considered that the poetry of Langston Hughes is without doubt the finest expression of this new Negro poetry. Alain Locke shared this view, writing that this work of Hughes in the folk forms has started up an entire school of younger poetry, principally in the blues form and in the folk-ballad vein. In reviewing the influence of folk forms on current poetry he cited Sterling Brown, with Hughes, a genius of folk values, the most authentic evocation of the homely folk soul.

A few years later, in 1936, Alain Lockes study, The Negro and His Music, was published by the Associates in Negro Folk Education as the Bronze Booklet Number 2. During the interim he had further examined the history and evolution of jazz, from its origins to the development of Classic Jazz and its influence on modern American music. Yet, while warning that we must never forget the folk originals, he observed that the term blues had become a generic name for all sorts of elaborate hybrid Negroid music. But that is only since 1910. Before that it was the work-songs, the love ballads, the over-and-overs, the slow drags, pats and stomps that were the substance of genuine secular music. These traditions he referred to collectively as Folk Seculars: Blues and Work Songs. He commended the collecting of Dorothy Scarborough who, in her work On the Trail of Negro Folk Songs, had found many examples of folk material both in the copied Anglo-Saxon four-line ballad form and in the more characteristic Negro three-line blues form. He also acknowledged the work of Guy B. Johnson and Howard Odum, who, a decade earlier, had published The Negro and His Songs and Negro Workaday Songs. As an appendix to the chapter Locke listed a number of recorded items, applying the constructive suggestions from his colleague, Professor Sterling Brown.

It seems that Alain Locke was not familiar with recorded blues when he was writing The Negro and His Music. This is surprising, since newly released records were extensively advertised in the daily newspapers addressed to the Black audience. The Chicago Defender carried large numbers of advertisements for 78 rpm records, especially those issued by the Paramount Company. As he was based in New York, Locke may not have read the Defender, but he would have had access to a number of regional Black newspapers, including the New York Amsterdam News and the New York Age. No doubt he could have seen the record advertisements in the Baltimore Afro-American and the Pittsburgh Courier. These and other newspapers carried many advertisements for specific records or, under the names of the companies, small groups of related issues, frequently with graphic illustrations of the performers and the subjects of their blues. Okeh, Columbia, Victor, Brunswick, and Vocalion all had race record catalogs and advertised regularly, often featuring releases by singers cited here.

Lockes collaborator, Sterling Brown, had a serious interest in blues. He contributed a feature on The Blues as Folk Poetry in Folk-Say, published in Oklahoma, and also wrote many poems in the blues idiom. Brown undoubtedly influenced Locke, as the latter acknowledged, but Locke also greatly respected the poet Langston Hughes, who wrote The Weary Blues and other blues-influenced poems. Locke was appreciative and curious to know more about the blues. Sterling Browns list of some forty titles (of which several were paired on the 78 rpm records noted) included blues songs by Bessie Smith, Clara Smith, Ma Rainey, Henry Thomas, Jim Jackson, and Tampa Red in the Vocal category, while Lonnie Johnson, Johnny Dunn, Peg Leg Howell, Jimmy Johnson, and Duke Ellington appeared under Instrumental. The Hall Johnson Choir was the sole provider of Choral Versions, the recordings by Paul Robeson, Rosamund Johnson, Frank Crummit (sic), Edna Winston, and Ethel Waters being listed as Seculars. Readers today would note anomalies in the list, such as the fact that Frank Crumit was White, and question whether the items were appropriately representative of the categories to which they were assigned. By this time in 1936, folk and blues records of considerable diversity had been issued for over fifteen years, with many selling in multiple thousands, so in certain respects the selection and its classification was unsatisfactory.

While some of the seculars (or proto-blues, as I have termed them since the 1980s) were still to be heard in rural areas when Locke was writing in the early 1930s, they were dying out and being replaced by newer idioms. Our knowledge today of the forms that they took and the regions where they may have developed, or which they represented, has largely been conditioned by recordings. Whether they were distributed and passed down as ten-inch 78 rpm wax records, seven-inch 45s and long-playing 33 rpm vinyl ten-inch, and later twelve-inch, LPs, or as tapes, cassettes, CDs, and more recently in electronic, digitized forms, we still depend on recordings of African American singers and instrumentalists made in the first half of the twentieth century, for what we know and appreciate of the sounds of the past traditions and their exponents.