BARRELHOUSE

WORDS

A BLUES DIALECT

DICTIONARY STEPHEN CALT UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS Urbana and Chicago 2009 by Stephen Calt All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Calt, Stephen. Barrelhouse words: a blues dialect dictionary / Stephen Calt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03347-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-252-07660-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Blues (MusicTextsDictionaries. 2.

Blues (Music)History and criticism. I. Title. ML3521.C35 2009 781.64303dc22 2009021912 To the memory ofRaymond and Nora Calt,two lovers of language

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

This work was begun in the late 1960s, a time when neither the vocabulary of blues songs nor the subject of bygone black language appeared to claim anyones attention. It was initially fueled by simple curiosity, a love of language, and by what was then a startling discovery, for me at any rate: that the most striking expressions found in blues songs were not, as usually depicted, poetic or metaphorical turns of phrase, but rather were slang terms. Blues abounded in slang that seemed to belong to the ordinary vocabulary of the singers and their peers.

Moreover, many unfamiliar terms occurring in blues songs were contained in dictionaries that did not classify these expressions as black or even American slang. On the premise that every enigmatic expression found on an old blues recording had been an aspect of actual speech, I compiled a list of such terms and attempted to track them down as best I could. In catch-can fashion, I questioned various aging blacks (particularly blues singers) regarding their meanings. Every discovery was fortuitous. The most unlikely one occurred at a Manhattan bus terminal eatery, where I was startled to hear a scruffy, middle-aged customer denounce the counterman as a jamboogera vexing word on my want list I had never encountered outside of a 1930 recording titled Jambooger Blues. The belligerent customer (whom I anxiously followed outside) was willing to indulge my curiosity about the term, though he obviously regarded me as something of a lunatic.

Unable to interest a publisher in the manuscript I had crafted, I became disheartened and abandoned it in 1976 in the fashion of a love affair gone bad. But for Ted Gioia, a fellow author with whom I began corresponding in 2005, the present work would have remained a stillborn enterprise. His curiosity about the dictionary led me to exhume the remains of the manuscript from a closet. Unexpectedly, most of my original papers were still intact after thirty years. It was on the basis of Teds enthusiasm that I returned to this project and updated it. In a palpable sense, this work is his as much as mine; apart from encouraging me, Ted took it upon himself to bring my manuscript to the attention of the University of Illinois Press.

I am certain that no writer has ever received greater assistance from another writer than I have received from my unusual benefactor, a man I have never even met in person. In a field where competitive egos run riot, he is a rare, magnanimous soul. In addition to Ted Gioia, I owe substantial debts to various people who assisted me in assorted ways, particularly Renatha Saunders (who provided firsthand information on entries surviving in black speech), Tim Aurthur, Christopher Calt, Owen DAmato, David Hinckley, Denis Lisica, John Miller, Maggie de Miramon, Xiomara Vogel, and Steven Wexler. I further wish to convey my gratitude to Richard Nevins of Yazoo Records, who graciously supplied me with his entire catalogue of CDs for this project, and to Chris Smith of Blues & Rhythm magazine, who (with equal generosity) provided me with copies of his informative column, Words Words Words, devoted to the language of blues songs. I also wish to thank Suzanne Ryan of Oxford University Press for her kind comments and beneficial criticisms concerning a version of this manuscript, and (posthumously) B. F.

Skinner, for steering the original version to his own publisher on my behalf. Finally, I would be considerably remiss if I failed to thank my editor, Joan Catapano, and Rebecca Crist of the UIP Production Department for their helpful and judicious stewardship, along with associate editor Tad Ringo, with whom I enjoyed a productive working relationship.

INTRODUCTION

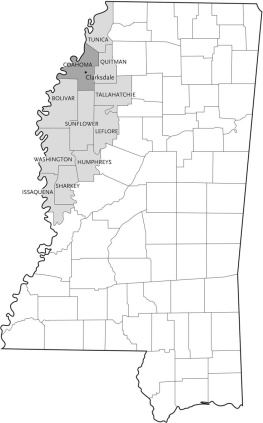

This idiosyncratic, discursive dictionary was assembled to unravel the most unusual, obscure, and curious words, expressions, and proper or place names found on race records, the music industry trade term for recordings intended for blacks. As a special category, such records were promoted between 1923 and 1949, when the term was replaced in

Billboard by its own clumsy confection, rhythm and blues, put forth in the interests of appearing less racist, and to retire a term that was associated with musical smut. Most race recordings consisted of blues songs, which served as the popular music of black Americans from around the turn of the twentieth century until (roughly) the outset of the Second World War, a span I have designated as the blues era. These songs attracted virtually no attention beyond the record industry when they were current; to the extent they were even noticed, they aroused contempt or indignation: [h]undreds of race singers have flooded the market with what is generally regarded as the worst contribution to the cause of good music ever inflicted on the public.

The lyrics of a great many of these blues are worse than the lowest sort of doggerel... (Talking Machine Journal, February 1924). Blues songs did not operate along the lines of conventional song composition, as it existed from the 1890s through the 1950s in what has become known as the Tin Pan Alley era of popular music. As much as a method of music making, blues were a medium of language. Blues songs were not written compositions in the customary Tin Pan Alley manner, involving literary or poetic diction on at least a rudimentary level. As declaimed by the singer-guitarists and singer-pianists whose lyrics are the crux of this dictionary, the blues lyric was a snippet of vernacular speech set to song, ostensibly referring to events and sentiments of the moment or recent past.

The casual, often crude, colloquial style of blues expression became an essential building block of rock and roll, which to this day is rooted in informal spoken English. At the turn of the twentieth century, when guitar blues were becoming fashionable among black entertainers in the South, blues stanzas apparently consisted of thrice-repeated conversational statements: Im goin where the Southern cross the Dog. (3)

I got arrested, no money to buy my fine. (3) The real subject of such songs was the singer himself, who was always at the forefront of his lyrics. The peculiar scaffolding of blues (generally employing lengthy ten-beat vocal phrases) enabled blues songs to exist as a series of complete sentences set to a meager melody. As blues evolved into stanzas of rhymed lyrics, dispensed in couplet form with the first line repeated, they retained their initial relationship to unadorned speech.

A blues song would typically involve disconnected, discursive statements in the form of verse held together by rhyme rather than by an express theme or topic. Throughout the 1920s, when blues were at their peak popularity, the blues lyric that was its prime selling point was a form of rhymed speech, conveyed in the style of English that was otherwise employed by the performers. These largely male individuals were African American, usually Southern (or from a Southern background), and denizens of what could be termed barrelhouse culture. Indeed, one Mississippian (Willie Moore) characterized the blues expressions he was asked to elucidate in the 1960s as barrelhouse wordsthe slangy speech one typically heard in bygone night spots known as barrelhouses, where revelers congregated to drink, dance, gamble, or consort with prostitutes. The patrons of such illegal establishments were not respectable figures in the eyes of society (black or white), and blues singers themselves had an almost Victorian sense of their own disreputable identities: I like low-down music, I like to barrelhouse and get drunk, too

This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Calt, Stephen. Barrelhouse words: a blues dialect dictionary / Stephen Calt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.

This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Calt, Stephen. Barrelhouse words: a blues dialect dictionary / Stephen Calt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.