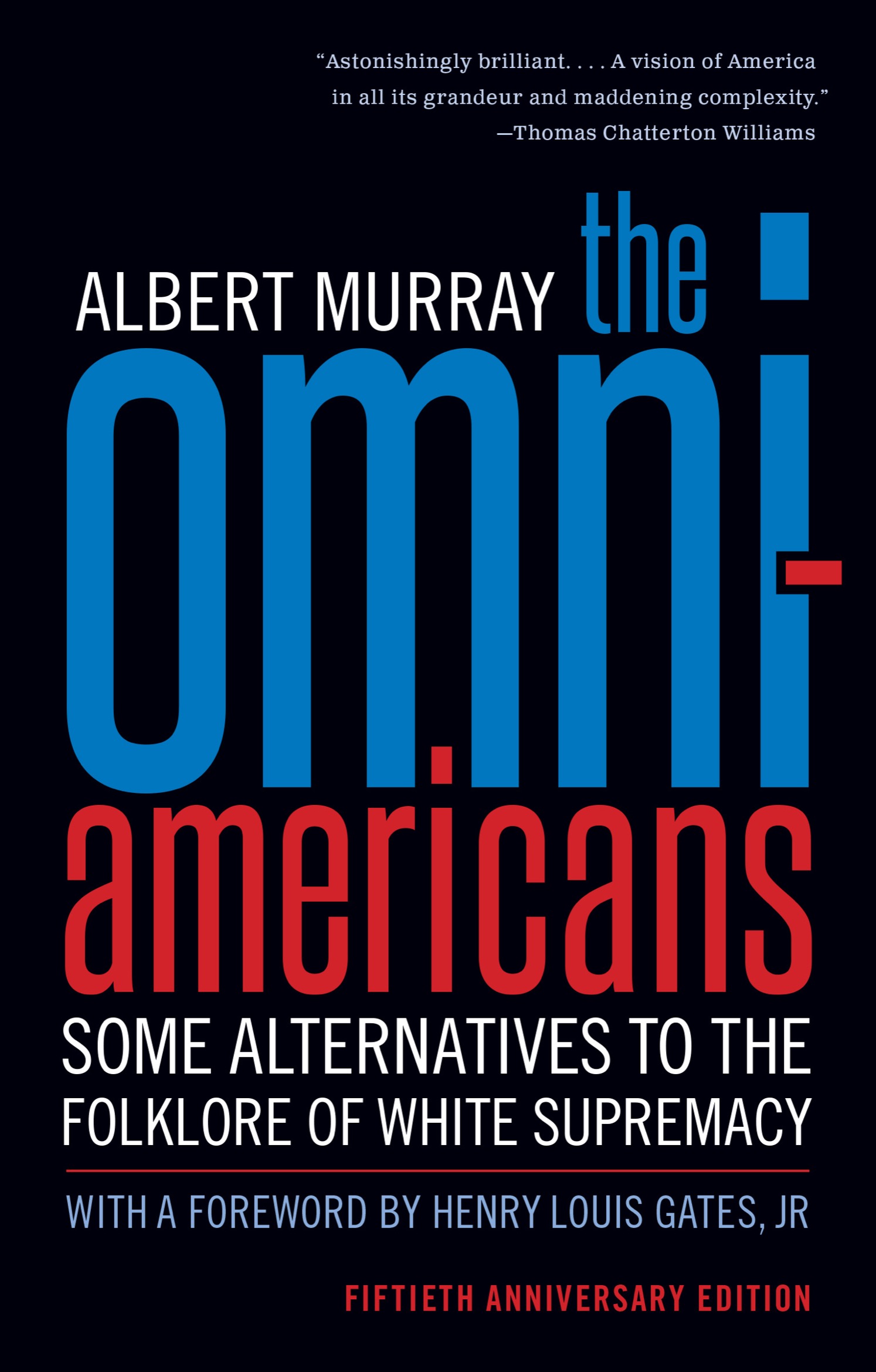

ALBERT MURRAY: THE OMNI-AMERICANS

Introduction and volume compilation copyright 2020 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

The Chronology, Note on the Text, and Notes in this book are drawn

from Albert Murray: Collected Essays & Memoirs, volume #284 in

The Library of America series, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Paul Devlin.

Published in the United States by Library of America.

Visit our website at www.loa.org.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever

without the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

The Omni-Americans copyright 1970 by Albert Murray.

Published by arrangement with The Albert Murray Trust

and The Wylie Agency LLC.

Distributed to the trade in the United States by

Penguin Random House Inc. and in Canada by

Penguin Random House Canada Ltd.

eISBN 9781598536539

Contents

Foreword

BY HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR.

P erhaps only someone who hasnt taken the time to study the history of slavery and the rollback to Reconstruction, or hasnt read Ta-Nehisi Coatess painstakingly detailed brief for reparations, could fail to see that black people have suffered devastating economic consequences from a quarter of a millennium of slavery followed by seven decades of de jure Jim Crow segregation. But reasonable people might wonder about the timing of making an endorsement of reparations, at the commencement of a presidential political campaign whose ultimate goal is the defeat of Donald J. Trump, one of the litmus tests for support of a Democratic candidate by the black or liberal electorate. And some might take the decidedly politically incorrect position that doing so at this time could be a costly mistake, given the fact that polls consistently show that relatively few white Americans support the idea of reparations. As I watched the hearings at the House of Representatives on H.R. 40 and listened to the compelling testimony of Mr. Coates, Danny Glover, Senator Cory Booker, and several other equally eloquent speakers, I wondered if the evening news would feature any black speaker raising this matter of timing. I wondered if anyone would have the courage or inclination to state a counterargument, to go, as it were, against the grain, if only as an exercise in the healthy exchange of ideas, without fear of being ostracized. It occurred to me that this was precisely the moment in which Albert Murray seemed to delight, the moment when he most eloquently found his voice: standing within the circle, yet critiquing it with the clear insight of someone outside of it. Going against the grain, registering counterpoint, insisting on polyphony was, for Albert Murray, not just an enjoyable intellectual exercise; it was an ethical principle, as well as an aesthetic one.

Albert Murray was one of the greats, and it was my honor to be in his orbit. When I was a junior faculty member at Yale, I used to take the New Haven line down to New York to spend Saturday afternoons with him at Books & Company on Madison Avenue. Both have long since crossed over to the mythical side of New York City life. The King of Cats I called him, easily one of the twentieth centurys most important aesthetic theorists of American culture.

Commanding on the page, Murray was equally impressive in the flesh: a lithe and dapper man with astonishing verbal fluency. He was a teacher by temperament and as he explained a point hed often say that he wanted to be sure to work it into your consciousness. The twentieth century had worked a great deal into Murrays consciousness. He was fifteen when the Scottsboro trial began, twenty-two when Marian Anderson sang at the Lincoln Memorial. He joined the Air Force when it was segregated and rejoined shortly after it had been desegregated. He was in his late thirties when Brown v. Board of Education was decided. He was in his forties when John F. Kennedy was killed and the Civil Rights Act was passed. He was in his fifties when King was shot and Black Power was proclaimed. He was ninety-two when Barack Obama was elected president, and ninety-six when Obama shocked the world by doing it again.

He was born Albert Lee Murray in 1916 and grew up in Magazine Point, Alabama, a hamlet not far from Mobile. His mother was a housewife, and his father helped lay railroad tracks as a cross-tie cutter. Everyone in the village knew there was something special about Albert. He knew it, too. After all, hed overheard his mother say shed raised him when his birth parentsmiddle class and educated but unmarriedcouldnt. Its just like the prince left among the paupers, Murray said cheerfully.

He earned his BS at Tuskegee Institute in 1939 and stayed on to teach. In 1941, he married Mozelle Menefee, his wife of more than seventy years, who, at the time, was a student at Tuskegee. Murray spent the last two years of World War II on active duty in the Air Force. Two years after his discharge, he moved to New York, where, on the G.I. Bill, he earned a masters degree in literature from New York University. It was also in New York that his friendship with Ralph Waldo Ellison, a former classmate at Tuskegee, took off. Ellison read passages to Murray from the manuscript that would turn into Invisible Man, and the two men explored the streets and sounds of Harlem together, hashing out ideas about improvisation, the blues, and literary modernism.

For a time, the life of the mind had to be tabled for the life of his family, and Murray rejoined the Air Force in 1951 to better support his wife and their beloved daughter Michele. He taught in Tuskegees ROTC program for much of the 50s. In 1962, he left the military, took his pension, and moved back to Harlem. Despite his friendship with Ellison, at this point Murray was little known in New Yorks literary circles. His career in the military, which found him overseeing the administration of large-scale operations in North Africa and in the United States, obviously contributed to that. But upon his return to the Big Apple, his articlescommentaries, reviews, and observations on the civil rights movementbegan to appear in magazines like Life and The New Leader and continued throughout the decade.

Then, in 1970, when I was a sophomore at Yale, with the Black Power movement ascendant, and the black ideological bullies, as Ive called them, circling, some espousing the Black Panther program, some touting Black Cultural Nationalism, and still others preaching the Nation of Islam, Murrays The Omni-Americans hit the shelves, a collection of the articles hed been producing during the previous decade. Secretly, many of us found the volume thrillingtransgressive, even. Murray wasnt interested in silos of black identity. We didnt need more sociological inquiry or separateness, he declared; what we needed was cultural creativity, nourished by but also transcending the folkways and traditions of black America.

It may seem ironic that the person who first urged The Omni-Americans on me was Larry Neal, one of the Black Arts founders. But Neal was a man of far greater subtlety than the movement he spawned, and he understood Murrays larger enterprise better than most. Where the black aesthetic movement had posited the black experience as a separate entity from white American culture, Murray argued that American and black American culture were mutually constitutive. There was no so-called American culture without the Negro American formal element and content in its marvelous blend, and no black American culture without its white American influences and forms.