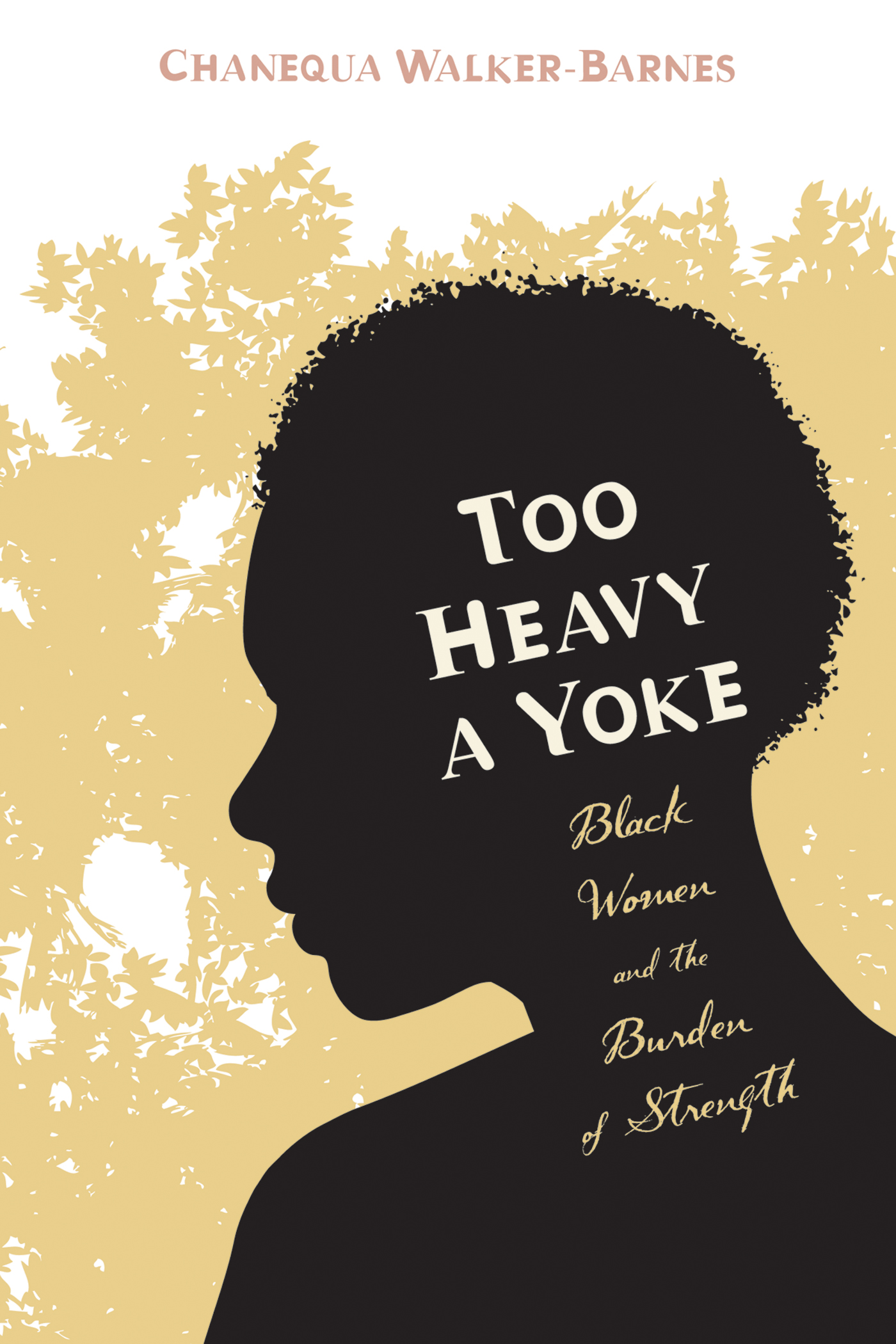

Too Heavy a Yoke

Black Women and the Burden of Strength

Chanequa Walker-Barnes

Too Heavy a Yoke

Black Women and the Burden of Strength

Copyright 2014 Chanequa Walker-Barnes. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical publications or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher. Write: Permissions, Wipf and Stock Publishers, W. th Ave., Suite , Eugene, OR 97401 .

Cascade Books

An Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers

W. th Ave., Suite

Eugene, OR 97401

www.wipfandstock.com

isbn : 978-1-62032-066-2

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Walker-Barnes, Chanequa.

Too heavy a yoke : black women and the burden of strength / Chanequa Walker-Barnes.

xii + pp. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

isbn : 978-1-62032-066-2

eisbn : 978-1-63087-192-5

. Women, BlackPsychology.. Women, BlackSocial conditions.. Women, BlackReligious life. I. Title.

HQ1161 .W35 2014

Manufactured in the U.S.A.

Unless otherwise indicated, biblical references are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright 1989 , Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

For the StrongBlackWomen upon whose shoulders I stand

my grandmother, Gwendolyn Johnson, my mother, Laquitta Walker, and my aunts, Lunetha, Jacobina, Marilyn, Belinda, Rochelle, Zeporia, Denette, and Linette

In memory of

Marion Walker, Erma Barnes,

and Tracey Ann Adams

Acknowledgments

V ariations of the ideas in this text were previously published in my article The Burden of the Strong Black Woman, in the summer 2009 edition of the Journal of Pastoral Theology .

A great cloud of witnesses has shepherded this project from its inception to its completion. I am especially grateful for my dear friends and colleagues Kathryn Broyles and Cheryl Kirk-Duggan, who have provided continual encouragement and feedback on several chapters. My writing group membersTonya Armstrong, Tina Ndoh, and Daphne Wigginsreviewed the book proposal and were vital in shaping the present form of the project. And my CCDA cohort members affirmed my voice when I still wasnt sure that I had anything valuable to say.

This project was birthed during my time as a seminarian at Duke University Divinity School. I am forever indebted to Willie Jennings, who helped me rekindle my passion for an academic career when I thought it had been snuffed out. Conversations and courses with several Duke faculty members were vital in shaping this book and my transition from clinical psychology to pastoral theology, including Esther Acolaste, J. Kameron Carter, Mary McClintock Fulkerson, Amy Laura Hall, and Tammy Williams.

Several feminist and womanist colleagues encouraged me to pursue this project when I was tempted to let it go, especially Monica Coleman, Trina Armstrong, and Pamela Cooper-White. Renita Weems gave me a healthy dose of You are enough! sister-medicine when I was tempted to believe that my education and credentials were insufficient for this project and for a career in pastoral theology. My understanding of intersectionality was expanded by my participation in the 2009 Spelman-NWSA Women of Color Institute. I am grateful to its organizers, facilitators, and participants, including Beverly Guy-Sheftall, Allison Kimmich, Bonnie Thornton Dill, Andrea Smith, and M. Jacqui Alexander.

I express my sincere gratitude to the Louisville Institute for their award of a First Book Grant for Minority Scholars, which funded a research leave during which much of this book was written. The feedback from my cojourners in the 2012 Winter Seminar was immensely helpful.

I am grateful for the support of my students at Shaw University Divinity School, Duke University, and McAfee School of Theology. Students in my courses on African American women at Shaw and Duke provided fertile soil for testing the ideas expressed in this book. And my students at McAfee have been incredibly supportive in the final stages of the journey, being patient with the slow grading of their newest faculty member and expressing eagerness for the project. Special appreciation goes to Sharlyn Menard for her assistance with the footnotes and bibliography and for helping ease my load generally as I completed the manuscript.

I also wish to express my appreciation for the women of the SISTERS group at Compassion Ministries of Durham, who allowed me to be a part of their healing journeys and who intersected mine.

I am eternally thankful for my husband, Delwin, and son, Micah, who have sustained me through the writing process and beyond with their love, patience, and laughter (especially their laughter!). I am more blessed by them than they could possibly know.

Introduction

The Personal Is Pastoral

The illusion of strength has been and continues to be of major significance to me as a black woman. The one myth that I have had to endure my entire life is that of my supposed birthright to strength. Black women are supposed to be strongcaretakers, nurturers, healers of other peopleany of the twelve dozen variations of Mammy. Emotional hardship is supposed to be built into the structure of our lives. It went along with the territory of being both black and female in a society that completely undervalues the lives of black people and regards all women as second-class citizens. It seemed that suffering, for a black woman, was part of the package.

Or so I thought.

T en years ago I came to a startling realization: I was a StrongBlackWoman, and being one was not working for me. Having recently crossed the threshold of my thirtieth birthday, I was in a state of physical and emotional crisis: high blood pressure, weight gain, chronic self-doubt, fear of making mistakes, insomnia, fatigue, headaches, frequent illnesses, low self-esteem, mood swings, and feelings of rage. On top of all that, I was lonely. Despite my constant attempts to do for and please others, I felt alienated, detached, and abandoned. I felt that there was no one whom I could count on, no one who could and would take care of me in the way that I took care of others.

I learned to be a StrongBlackWoman early in life. I am the eldest child of a single mother, with a brother eight years my junior. With my mother working long, hard hours to support us (often twelve-hour stints on the third shift), I had to step in to help take care of the family. By the age of ten, I was capable of waking up and getting myself and my brother dressed and fed so that we would be ready when my mother returned home from work to take us to school and daycare. By fourteen, my afterschool routine consisted of taking the city bus to pick up my brother from daycare, helping him with his homework (and doing my own), supervising while he played outside, cooking dinner, cleaning the kitchen, and getting him bathed and in bed. In child development terms, I was a full-fledged parentified child.

Over the years my caretaking tendencies expanded to include everyone around mefamily, friends, co-workers. It was a natural (and expected) progression. I was constantly concerned with the needs of others, always trying to be helpful. I was so accustomed to taking care of others that I felt pangs of guilt anytime that I did something for my own pleasure or, worst yet, did nothing at all (that activity known to others as relaxation). Over-extending myself became my modus operandi. I was living in a state of serious self-care neglect. Of course, I did not call it neglect. I called it being responsible. In fact, I prided myself on being the most responsible person I knew. And my high sense of responsibility was rewarded often by others who were pleased with me and the things that I did for them.